Dr. Avis Williams: Beyond the Bridge

Dr. Avis Williams' legacy of leadership in Selma City Schools

For Dr. Avis Williams, leading a district like Selma City Schools has been a dream come true—but it hasn’t been without its challenges. Selma is the fastest-shrinking city in Alabama; the surrounding county is one of the poorest in the state; and Selma City Schools was under state intervention and struggling with high turnover rates when Williams first took the helm.

During her time as Selma’s superintendent, Williams has seen the district through their state intervention and been named one of NSPRA’s 2021 Top Superintendents to Watch. Now, while the rest of the country is scrambling over shortages, Selma City Schools is swimming in a talent pool of their own making. “What we don’t have is a shortage of leaders,” Williams tells us. “In the event that we had a principal vacancy—if we had five vacancies—our only problem would be deciding which leader to place where.” How are they doing it? By investing in aspiring leaders who reflect their community.

It probably won’t come as a shock that approximately 68% of teachers in the United States are female. Yet in a survey done by AASA, only 27% of superintendent respondents were female, and only 1.4% of superintendents were Black women. The superintendency is still overwhelmingly white and male; our teachers—and our students—are not.

Dr. Avis Williams is responding to our nation’s critical need for Black female leaders. She’s taking a new view of leadership altogether by looking right in front of her. With pipelines like Selma City Schools’ Aspiring Leaders Academy (ALA), Williams is investing in the future leaders who are already in the room—and producing a leadership surplus.

Winding Paths

Williams’ career in education didn’t begin on a college campus. It began in her childhood home, where she played school with her dolls in a make-believe classroom. As a student, Williams had a passion for learning, eventually becoming a self-professed bookworm. The only time she ever got in trouble at school, she was reading a novel instead of focusing on her lessons. “I couldn’t imagine not loving reading,” Williams says. “Part of it was an escape. Home life wasn’t always great, and reading was a way to pour myself into something.”

But even with a natural love of learning, Williams’ path to becoming an educator was anything but straightforward. She was a top student in her class—and yet no one ever talked to her about going to college. “I got scholarships, but I didn’t know what to do with them,” she tells us. “No one in my family had ever gone to college before.” Instead of attending a university after high school, Williams followed the only path she knew. Like her brother and sister before her, she joined the U.S. Army.

Williams’ time in the military brought her to Alabama, where she eventually put herself through college while working as a personal trainer. She even hosted a radio show called “Ask Avis,” where she answered callers’ questions about fitness. But it wasn’t until she got a divorce that she began to think seriously about a career change. “I was still doing personal training full time, and our daughter was only two,” Williams tells us. “Taking a baby to the gym at 5 a.m. to train clients is a little rough.”

So Williams chose to pursue a position teaching both P.E. and English. “Within a couple of years, I knew I wanted to expand my reach in terms of what I could do in education,” she says. “So I worked on getting my master’s degree and administrative certification within the first three to four years that I was in the classroom.”

It took years for Williams to find her way to a career in education. If she’d understood her opportunities from the beginning, that might not have been the case. “I have no regrets about serving my country—it was one of the best experiences of my life—but I still should have been aware of my options,” she says. “I want to make sure our young people understand that they have choices.”

The Selma Superintendency

It’s important to Williams that her students have more support throughout their educational careers than she did. In some ways, Williams sees herself as the poster child for what education can do. “I just want young people to understand that education is the key,” she tells us. “I grew up in poverty, and, in my heart, I have always wanted to serve in communities where the needs were great. Had it not been for education, I don’t know where I would be.” It’s that passion for learning—and for sharing education with under-resourced communities—that motivated Williams to climb all the way to the superintendency.

When Williams decided to take the top job in Selma, a number of people wondered why. With high poverty, high crime rates, and the fact that Selma was under state intervention at the time—why would Williams want to take on such a tremendous challenge? Her answer: “Somebody needs to, and it needs to be somebody who cares about these babies who look like me. When I look at them, I see me. I was just one or two decisions away from not being where I am right now.”

To get to where she is now, “it’s been a lot of uphill battles because of the intersectionality between being Black and being a woman,” Williams says. “I will tell you: the patriarchy is real.” On more than one occasion, Williams has found herself faced with roadblocks her white male peers don’t have to contend with. “As a Black woman, I have found that I have to be overly prepared,” she says. “I have to check all the boxes in a way that my white male colleagues don’t.”

Before her superintendency, Williams had served as an elementary, middle, and high school principal. She had also held two central office jobs. ”But they still looked at me and said: Well, she doesn’t have superintendent experience,” she tells us. “And I thought: Could you give me some, maybe?”

According to Williams, though, it’s more than just a problem with hiring institutions. “We’re our own worst enemies sometimes, too,” she says. “We don’t help ourselves any when we second-guess what we bring to the table, when we don’t take advantage of the opportunity to speak up. One of the things that I learned real fast was not to let a man talk over me.”

All this boils down to an important lesson. Over the course of her leadership journey, Williams says she’s learned that “people in certain spaces are not going to clear the way for you automatically.” It’s about choosing not to be silent. “You deal with the obstacles you’re given and you make the most of it,” she says. “I have a choice as to how I respond, and I choose to respond by making my voice heard.”

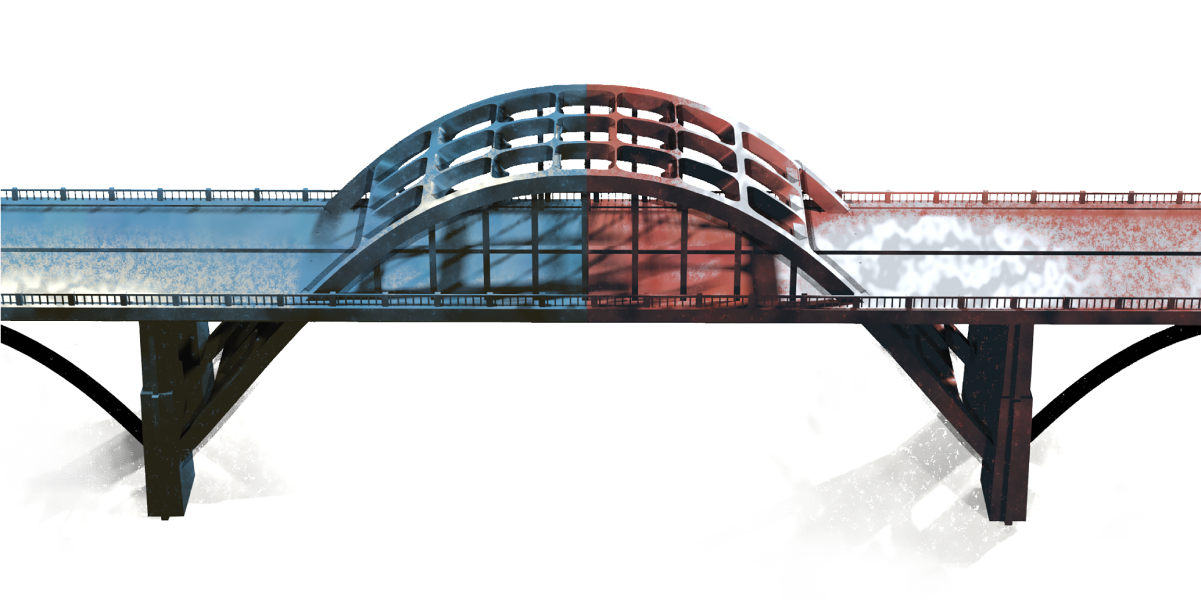

Bridge Crossing

The power of the human voice isn’t just something Williams has modeled for the students of Selma—it’s a historical truth they’re reminded of annually. Students all over the country learn that on Bloody Sunday, people risked their lives for their right to vote. They learn that their democratic society hinges on what happened when a group of civil rights marchers was barred from crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Unlike most students in the United States, though, Selma students contextualize their learning with the annual Bridge Crossing Jubilee, a local celebration held to commemorate the marchers who made history in 1965.

Every year, Selma sees several big names in politics visit town for the Jubilee. This year, one of those visitors was Vice President Kamala Harris. “It meant a lot that someone who is active in the Biden administration was here,” Williams says. “I was really happy to see our vice president, as opposed to someone just using Selma as a backdrop for their political speech.”

The Bridge Crossing Jubilee is a necessary reminder of a tragedy that was the direct result of racism. But what happens after the ceremony ends? “I do think people use Selma and then go back home,” Williams tells us. After everyone leaves, Selma keeps struggling. “I think a lot of people don’t realize the state of Selma right now,” she adds. “A lot of people don’t realize the poverty that’s here.”

Recently, Williams had lunch with a student as part of a program she created called Lunch and Learn. During Lunch and Learn, students are asked: What are your hopes and dreams? What do you need from your school? One particular student said his dream is to make Selma a safe place. He hears gunshots at night. His cousin’s brother was killed last year. According to Williams, this is what people outside the community sometimes miss about Selma.

“But it gave me such hope,” Williams says. “This is a fourth grader talking about improving the community.” That’s what she loves about the Bridge Crossing Jubilee, too: “It never stops short of letting us know there’s still work to be done.”

Leaders Who Look Like Them

Williams was drawn to Selma not just because she sees herself in the students, but because she recognizes how crucial it is for students to see themselves in their leaders. “We need to understand that seeing is believing,” she tells us. “Children of color need to see teachers who look like them. They need to see leaders who look like them. They need to see people in the community, positive role models, who look like them.”

Unfortunately, our school leaders often don’t reflect our school communities. So what do we do? Williams’ answer is to establish internal leadership pipelines like Selma City Schools’ Aspiring Leaders Academy.

What it is:

When it came to explaining the ALA to her staff, “the biggest thing we had to overcome was the word ‘leader,’” Williams says. “It bothered me that teachers didn’t see themselves as leaders. We had to make it really clear that we’re not training you to be a principal. If you do want to be a principal, we’ll prepare you—but that’s not all this is about. We had to really make it clear in our marketing and communication that this is for anybody.”

In a recent presentation, Williams described the ALA as being “designed for current Selma City Schools employees who desire to develop leadership skills that will enable them to support students and stakeholders.” Aspirants cultivate their leadership skills by participating in professional development and receiving leadership coaching. They also engage in what Williams’ presentation described as “experiences that provide opportunities to make schools and departments more joyous and effective.”

Who it’s for:

Recruiting applicants for a program like the ALA is no small feat. In fact, Selma City Schools decided that if they were going to do it at all, they were going to do it right. That meant building a whole new position to spearhead the implementation of the ALA: the Director of Teacher and Leader Development. According to Williams, the new position helps circumnavigate any conflicts of interest. “A superintendent can’t really do a whole lot of employment counseling,” Williams tells us, “but the Director of Teacher and Leader Development can.” Even better, the current director was hired from within the district.

While some applicants decide to apply on their own, others are specifically sought out, or “tapped.” Sometimes the district taps staff members who have applied for leadership positions in the past but didn’t get them. Other times, they target staff members who have a real “spark,” who can bring something vital to their cohort. Williams says that’s because “in a cohort, you learn a lot from your classmates, too.”

Although Williams and her team are intentional about identifying staff members who are a good fit for the program, they’re also serious about making space for everyone. So far, Selma City Schools hasn’t turned away a single applicant. They’ve decided that if they ever have too many applicants, they’ll just have two cohorts that year.

Why it’s important:

According to Williams, programs like the ALA are inherently students-first practices. “An effective teacher is key,” she says, “but an effective school leader is also essential in terms of improving outcomes.” In fact, research shows that school leaders are second only to classroom teachers when it comes to impacting student learning. “Effective school leaders are directly tied to student outcomes,” Williams says.

But perhaps one of the most compelling reasons to implement a program like the ALA is the effect that a leadership pipeline can have on diversity and equity in your school district. “We wanted to make sure that our leadership pool resembled our community,” says Williams. “And one of the things that I’m really intentional about is making sure women have a seat at the table.”

When it comes down to it, programs like the ALA are necessary because educators deserve workplaces that pour into them just as much as they pour into others. “When I talk to our leaders who have participated,” Williams tells us, “they feel empowered. They feel supported, and their confidence is so much greater than it was before.”

What it’s led to:

Now in their third cohort of the ALA, Selma City Schools is in a very different boat than most districts throughout the country. In fact, of the 11 members who were in the first cohort, eight have been promoted. They’ve also observed the ALA’s capacity to clear the way for more female leaders; one recent cohort was all women. Part of the ALA’s success is, no doubt, thanks to Williams’ dedication to mentorship. “When you’re in a leadership role,” she says, “it’s your responsibility to make sure that you are providing mentorship and support to others.”

Positioning qualified people for success also brings Williams great joy. Thinking back on her proudest moments with the ALA, Williams tells us about a staff member who dreamed of becoming a principal. She’d applied a couple of times, but wasn’t hired—until she joined the ALA. Now, she’s a principal in the community where she herself went to school. “Seeing her sense of pride, seeing her family celebrating her as a principal—that brings me joy,” Williams says.

And she’s not stopping with Selma. Recently, Williams attended a graduation at AASA’s National Conference on Education. She noticed academies for aspiring female superintendents and aspiring Latino and Latina superintendents—but “nothing for Black people,” she tells us. “So I texted one of the directors, and I said: We need to do this.” After a couple of calls and Zoom meetings, she got the green light. Now, she’s working with AASA on implementing an academy for aspiring Black superintendents.

“I want to create a program that gives us the space to work on challenges and identify obstacles, but also get down to solutions,” Williams says. “How do we make sure that when decisions are being made about who’s going to sit on national boards or serve at the state or national level, we’re not only eligible, but the obvious choice?”

From the Ground Up

Selma, Alabama, is more than a moment in American history. It’s a community with local issues, many of which stem from the same racism that brought marchers to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in the first place. Other issues are the direct result of tangled systems that proliferate poverty and gender gaps. They’re what have children hearing gunshots and women struggling to believe they could ever be qualified leaders.

And that’s exactly why Dr. Avis Williams is pushing back. Her leadership is a symbol of what happens when education is prioritized at every level and when people in power lift from the ground up. While working as the superintendent of Selma City Schools, she has made it her mission to put power back into the hands of the community.

And just as Selma is more than a moment in American history, Williams is more than a moment in Selma’s history. As a force for equity, she’s created new systems, like the ALA, that will live on—even as her time in Selma comes to a close.

At the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, Williams will be moving on in her own leadership journey to serve as the superintendent in New Orleans. For the first time in 181 years, NOLA Public Schools will have a woman serving as their permanent superintendent—and it’s someone who’s spent her entire career leading the charge for equity.

In a thank you message to the Selma community after announcing her departure, Williams said, “I could not be more elated and proud and grateful to have been able to lead this amazing work over the last five years.” Thanks to the ALA, Williams can move on knowing that Selma’s growing community of leaders will take up the reins and continue writing their own narrative. Our country may be well acquainted with Selma’s past, but, thanks in no small part to Williams, it’s up to the people of Selma to decide their future.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!