SchoolCEO Conversations: Coping with COVID-19

How superintendents are boosting morale amid extended school closures

First, it was one week. Then, it was two. Then a month. Now, most districts around the country are facing a bitter reality: schools closing for the remainder of the academic year. But as we all adjust to this new normal, school leaders are finding incredible ways to do what they’ve always done best: focus on the well-being of their students. Here are a few star superintendents who stood out to us.

Story Time with the Suit Guy

Superintendent Mike Nelson, Enumclaw School District, WA

Superintendent Mike Nelson is a beloved fixture in Enumclaw School District. He’s been there 21 years, nearly 14 as superintendent. Lovingly known as “The Suit Guy”—a reference to his colorful, patterned suits—his visibility and consistency have given him a valuable asset: credibility. So when COVID-19 closed Washington’s schools, Nelson knew it was his job, as a school leader, to set the tone for the closure.

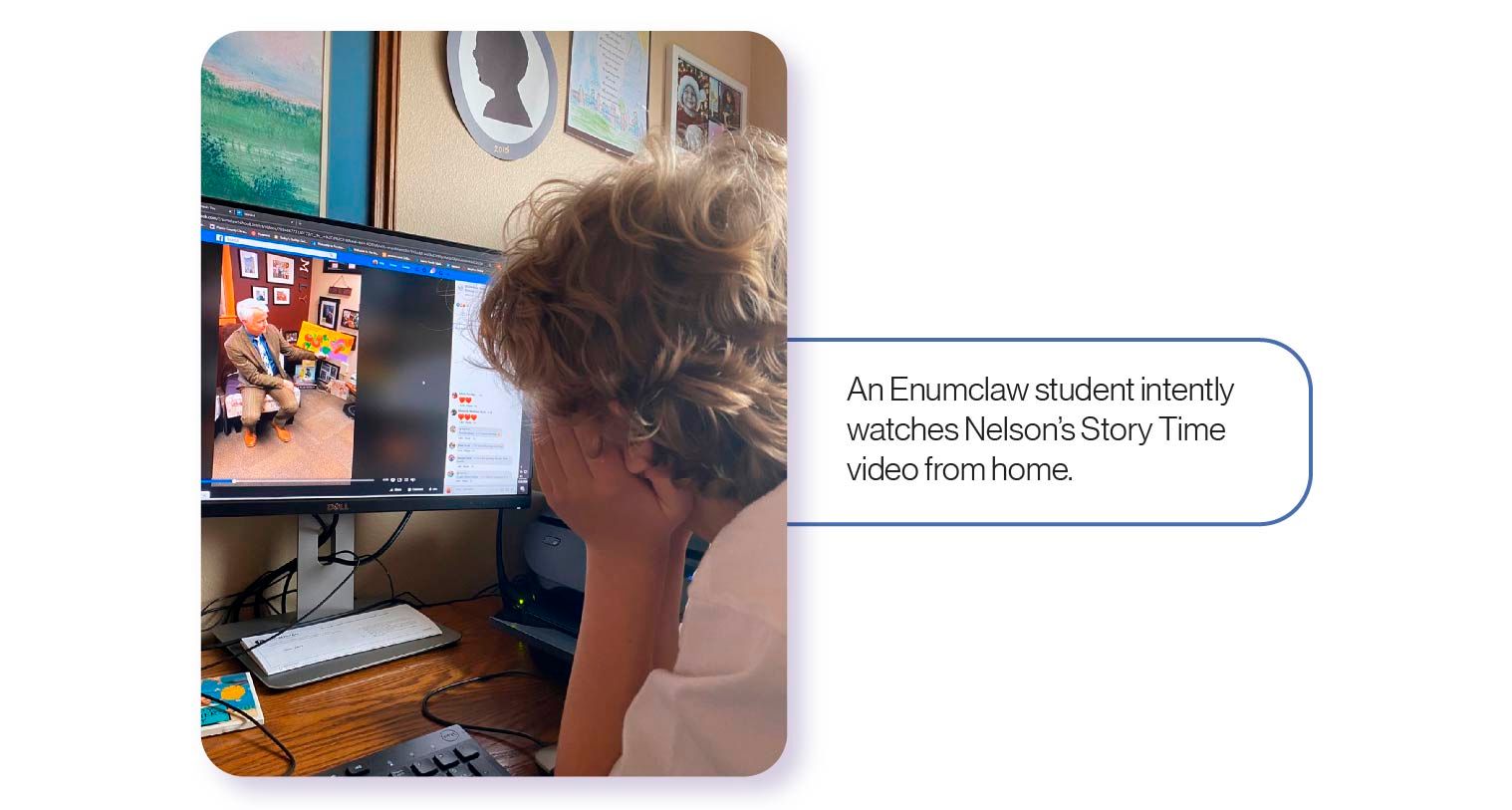

A former elementary teacher, Nelson went back to his roots. “It just comes naturally to me to read a story,” he says. So each school day since the closure began, he’s hosted “Story Time with the Suit Guy,” reading a children’s book live on the district’s Facebook page. With a calming presence reminiscent of Mister Rogers, he welcomes the district’s kids into his office and shares a story. He often includes an accompanying activity, whether it’s hard-boiling an egg, planting seeds, or making Rice Krispie treats.

The videos not only engage Enumclaw’s students and parents, but also provide teachers with invaluable professional and emotional support. “All of our elementary teachers are now connecting that as part of their daily work with students,” Nelson says. “And it helps them realize their superintendent’s in it with them.”

They’ve also seen ripple effects in the greater Enumclaw community. When a local author started selling books to raise money for a food bank, a resident donated $100 to send a single copy to Nelson—and pledged another $100 if he’d read the book for Story Time. “So as a result of reading that book, $200 went to the food bank,” Nelson says. “Those little ripples are fun.”

Nelson’s emphasis on reading hasn’t stopped at Story Time. “One day,” he tells us, “I started thinking—We’ve got to get people united in this community. What if we did a reading challenge?” So the district introduced “Read Together, Learn Together,” an initiative encouraging the entire Enumclaw community—even those not directly connected with the schools—to read more and keep track of their reading time. “People go to our website and log their minutes,” Nelson explains. By June 19, the official last day of school, Enumclaw hopes to have read a collective 10 million minutes.

For Nelson, both Story Time and the reading initiative are about more than just literacy. “Our kids are watching us right now,” Nelson says. “How are we modeling how to be resilient, how to be kind and compassionate during times of adversity, how to have empathy for one another?” Sometimes, it’s as simple as reading a story.

Taking the Classroom Outside

Superintendent Dr. Howard Carlson, Wickenburg Unified School District, AZ

Like many districts, Wickenburg Unified is working to provide for their families’ physical needs during this trying time. They’re providing food for pickup and delivery, distributing Chromebooks, and working with local providers to supply internet access to families who need it. But once those needs are met, says Superintendent Dr. Howard Carlson, “we’re starting to shift our focus toward the social and emotional support that our families and students need.”

“Oftentimes they’re locked at home, and although they can get outside, they’re not able to connect with others in person,” Carlson tells us. “We’re trying to figure out ways to make sure kids can stay connected and healthy.” For some families, that means wellness checks, or digital meetings with counselors who can provide resources. For others, it simply means moving the classroom to the backyard.

“We aren’t just delivering an educational opportunity,” Carlson explains. “We’re trying to tie in scenarios where students get outside and do something. It couples the educational component with the social-emotional component, dealing with that mental health piece—getting outside, getting in nature, getting into the sun. That’s a real innovation, because normally when kids go to school, they go to a classroom and they learn. Here, you have an opportunity to get them outside.” This approach to learning forces teachers to get creative, but Wickenburg’s staff has jumped at the challenge. “Our high school art teacher climbed one of the peaks out here, and, along the way, took pictures of the various wildflowers—then made that into a lesson around painting wildflowers,” he says.

Even the district’s social media has turned to nature for inspiration. “We’re in Arizona, in the Sonoran Desert, and this is a beautiful time of the year,” says Carlson. “Wildflowers and cactuses are starting to bloom. So on social media, we’re sharing a lot of pictures of that natural beauty, trying to shift everyone’s focus beyond the virus.”

“It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood!” reads one Facebook post, accompanied by photos of vibrant pink flowers and the open desert sky. “We hope everyone is finding time to enjoy their surroundings.”

Carlson knows that his staff needs the benefit of fresh air just as much as his students—which is why he’s practically requiring them to spend time outdoors. “I think it’s going to be of vital importance—telling people they need to get outside,” he tells us. “Take a walk, walk the dog, whatever the case may be. You need to be able to get that fresh air. That’s going to help keep us centered as we go through this.”

When Education Isn’t #1

Superintendent Robbie Binnicker, Anderson School District One, SC

At Anderson School District One, the COVID-19 crisis has demanded a shift in priorities. “As the superintendent, it’s very hard for me to say that education isn’t the most important thing,” says Robbie Binnicker. “But right now, it’s not. We’ve got families that are really struggling with new challenges, whether that be sick family members or parents losing their jobs or older kids having to watch younger siblings. Right now, education should not be adding stress and anxiety to people’s lives.”

That philosophy has been the district’s guiding light since South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster closed all the state’s schools on March 15. In the district’s response protocol, they list three main priorities: safety first, anxiety reduction second, and learning third. Reducing anxiety, for Anderson One, means providing thousands of meals for kids, both onsite and at bus stops. It means continuing to pay all staff for as long as possible. And it means making sure the stressors of this situation don’t negatively affect a student’s long-term academic success.

“We don’t have any way to know right now why a student isn’t turning in quality work,” Binnicker explains. “It could very well be a motivation issue, but it could also be a myriad of other things that the kid doesn’t have any control over.” So for this fourth quarter, the district is changing their grading system; instead of letter grades, assignments will receive one of two distinctions: “Meets Expectations” or “Needs Improvement.” At the end of the school year, teachers may add zero, one, or two percentage points to a student’s third quarter grade average; that will be their final average for the year. This quarter can only help students academically, not hurt them.

“We tried to find a balance so that there was an incentive for kids to do their work without it causing nervous breakdowns,” says Binnicker.

The district has many ways of looking out for the emotional well-being of its students and families. “Early on, every school divided their kids up and gave them to staff members who really couldn’t work from home—teachers’ assistants, attendance secretaries, receptionists, one-on-one special education aides,” Binnicker tells us. “For three and a half hours a day, all of those employees are calling and checking on folks, asking, How are things going? Do you have enough food? Are you having issues with the light bill?” Not only do these check-ins show families the district cares, but they alert Anderson One to any potential problems that might keep students from working—issues with technology or other stresses at home. Most families get a call at least once a week.

“The people making the calls are getting a lot out of that, and the parents and kids love it,” Binnicker says. “It’s great PR for our district.”

Like any educator, Binnicker wants to make sure his students are learning. But “you’ve got to keep the main thing the main thing,” he says. “You’ve got to know that you’re making things as good as you possibly can for the students. That’s the goal that keeps every educator going: knowing you’re making a difference in the life of a kid.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to have a digital copy of the most recent edition of SchoolCEO sent to your inbox.