Dr. Sharon Desmoulin-Kherat: "A Community Can"

How one finalist for AASA's National Superintendent of the Year leads with community collaboration at Peoria Public Schools

A COMMUNITY CAN

How Dr. Sharon Desmoulin-Kherat is working

for—and with—the people of Peoria, Illinois

Peoria, Illinois, has gone by a lot of names. Thanks to its location on the banks of the Illinois River, it’s been called “The River City.” Its abundance of distilleries earned it the moniker “The Whiskey City.” The locals call it “P-Town.” But in recent years, a new nickname has begun to catch on: “The City of Gratitude.” And according to Dr. Sharon Desmoulin-Kherat, superintendent of Peoria Public Schools (PPS), that’s the name that resonates the most. When it comes to her community, she says, “I’m grateful—always grateful.”

A native of Dominica, West Indies, Desmoulin-Kherat first came to Peoria as an undergraduate student attending Bradley University—“and the city has embraced me every step of the way,” she says. Now, more than 30 years after she arrived, her love for Peoria is still palpable. You can hear the pride in her voice as she describes her city, from the booming industrial scene to the manageable traffic. But most of all, she says, “I love the people.”

Desmoulin-Kherat has served the people of Peoria for more than 25 years, the last 10 as superintendent. And her love for the community isn’t just a driving force behind her leadership—it also enables the deeply collaborative work that’s changing the city for the better. “We have a saying here at Peoria Public Schools: ‘Schools can’t do it alone, but a community can,’” she tells us. Desmoulin-Kherat doesn’t just work for the community she loves; she works with them.

A Nontraditional Start

When she first arrived at Bradley, Desmoulin-Kherat wasn’t planning to become an educator. After growing up in a family full of them—including her father, a headmaster at an all-boys school—she wanted to try something new. “I actually started off as a computer science major,” she tells SchoolCEO. “I spent my freshman year programming and debugging.” But it didn’t take her long to realize that the world of computers and algorithms wasn’t for her. She needed to work with people—and the more she thought about it, the more she realized education was a good fit. “It was natural,” she says. “Education was just in my DNA.”

After changing her major, Desmoulin-Kherat completed her student teaching at PPS, beginning her decades-long relationship with the district. But she didn’t go straight from Bradley to the traditional classroom. In the late ‘80s—long before current teacher shortages—the job market for teachers was competitive, and though she applied at PPS, she wasn’t hired. Instead, she went to work for Peoria’s Tri-County Urban League, teaching middle schoolers in their Tomorrow’s Scientists, Technicians and Managers program (TSTM). After just four years, she became director of the entire program.

“That provided valuable insight into leadership for me, especially in a community that faces unique challenges,” she tells us. “So much of my work was advocating for equitable education, creating strategies to address educational disparities and working very closely with the community”—skills that would continue to serve her for the rest of her career. “If I had just gone straight into traditional teaching, I would never have gotten that experience,” she says. “It made me who I am today.”

All the while, Desmoulin-Kherat kept PPS on her radar—and the district kept her on theirs. The district collaborated with the Urban League often, and they were impressed with the TSTM director. “District HR would come and say, ‘Hey, we need you to come and do this or do that,’” Desmoulin-Kherat tells us. “And I kept saying, ‘Well, I still have some things to do here.’” But after about three years, she finally applied to be an assistant principal at one of PPS’s magnet schools, and as they say, the rest is history.

Desmoulin-Kherat spent the next 13 years in Peoria as an assistant principal and then principal at two different schools. She did leave the district briefly—spending two years as district transformation officer at Springfield Public Schools, then two more as associate superintendent at Danville Public Schools 118—but it wasn’t long before she found her way back home again. In 2015, she accepted the superintendency at PPS, and she’s been there ever since.

Filling Teacher Vacancies

When Desmoulin-Kherat first came aboard as superintendent, PPS was facing a workforce crisis. Gone were the days when schools had more applicants than they did vacancies. That year, PPS had more than 100 openings for teaching positions across its 27 school sites. “It was impacting the culture and climate of the schools, especially those in disinvested areas,” she says. “So when I came on, I knew we would have to come up with some bold strategies to address this.”

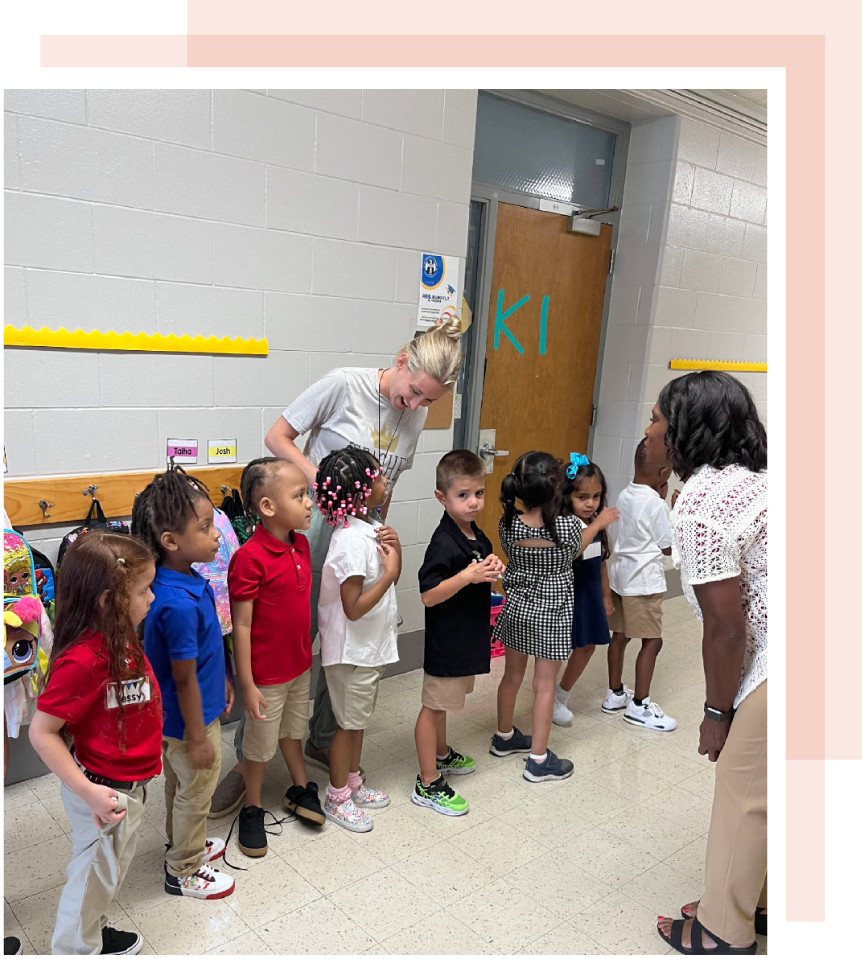

Some of those strategies were fairly straightforward, like hiring a recruiter and offering jobs to promising student teachers before they even graduated. Others, like relaunching Peoria’s defunct grow-your-own (GYO) program, were more involved. Spearheaded by program coordinator Linda Wilson, Peoria GYO now recruits locals who might be interested in teaching—from recent high school graduates to paraprofessionals to career changers—and provides them with financial support, academic help, childcare, mentoring and more. In exchange, these newly minted educators pledge to teach at PPS for at least five years.

The program is about more than just filling vacancies—it’s also about providing Peoria’s students with educators who look like them. In 2021, more than 85% of PPS teachers were white, compared to just under 20% of its students. With 14 Peoria GYO graduates so far—many of them people of color—the program is on track to change that. “And those individuals, all of them, are from the community,” Desmoulin-Kherat says. “They’re not going anywhere.”

And Peoria GYO isn’t the only trick up the district’s sleeve. In 2023, PPS also introduced their Teacher Ready program “for individuals in our sub pool who have a bachelor’s degree, but not a teaching certificate,” Desmoulin-Kherat says. The district pays 100% of candidates’ tuition costs for a self-paced online alternative certification program; in return, graduates teach at PPS for three years. “We have a good 40 candidates in that pipeline,” Desmoulin-Kherat explains.

But perhaps the most inventive strategy for reducing Peoria’s teacher shortage has been recruiting educators from overseas. After a long application process, PPS became one of the first districts in the country to sponsor J-1 visas. Now, the district employs more than 100 international teachers from 16 different countries. Their visas last for three years, with an option for a two-year extension.

Desmoulin-Kherat says that PPS provides plenty of support to help these new teachers acclimate to the U.S.—from professional development to mentorship to additional support in the classroom. “But they’re not only exposed to American culture; they also share their cultures with their peers and with the children,” she says. During Black History Month, for example, teachers from across Africa prepared traditional dishes to share with their coworkers at lunch.

The program has been so successful that PPS is even sharing its international teachers with other districts in Illinois and beyond. “We have no objection letters from Texas, Michigan and Washington, D.C.—which means that if we have too many applicants and their school districts are interested, we can place teachers there as well,” Desmoulin-Kherat explains.

The results of all these efforts? An alleviated teacher shortage, a 10% increase in staff diversity and a 9% increase in teacher retention. “Our vacancies now are minimal,” says Desmoulin-Kherat. “And we’re still going strong.”

Wrapping the Community in Support

Teacher recruitment and retention weren’t the only challenges facing Peoria in Desmoulin-Kherat’s first years as superintendent. In 2018, the district’s high school graduation rate was just 69%, well below the state average. But even more critically, many families in the Peoria community had unmet physical, social, and emotional needs. Desmoulin-Kherat believed that—as is so often the case—the three were connected.

In response, PPS opened the Wraparound Center, “a one-stop shop connecting students and families to services that will help them meet their basic needs.” Housed in one of the district’s K-8 schools, “it’s located in a very distressed zip code in our community—one of the most economically distressed in the United States,” says Desmoulin-Kherat. The area is a food desert, without grocery stores or other access to fresh food. Neighborhood residents also have inadequate access to housing, healthcare, job opportunities and other necessities.

The Wraparound Center aims to change all that. There, families can access a multitude of services through PPS’ partner agencies, from a food pantry to healthcare providers to a trauma recovery program and much, much more. In addition to these partnerships, PPS has also hired staff specifically for the center. “For example, we’ve hired seven justice advocates,” Desmoulin-Kherat explains. “Children who are involved with the criminal justice system are more likely to drop out of school—so these adults go to court with those children, get them reenrolled and help them navigate so that they can graduate and we can reduce that recidivism.”

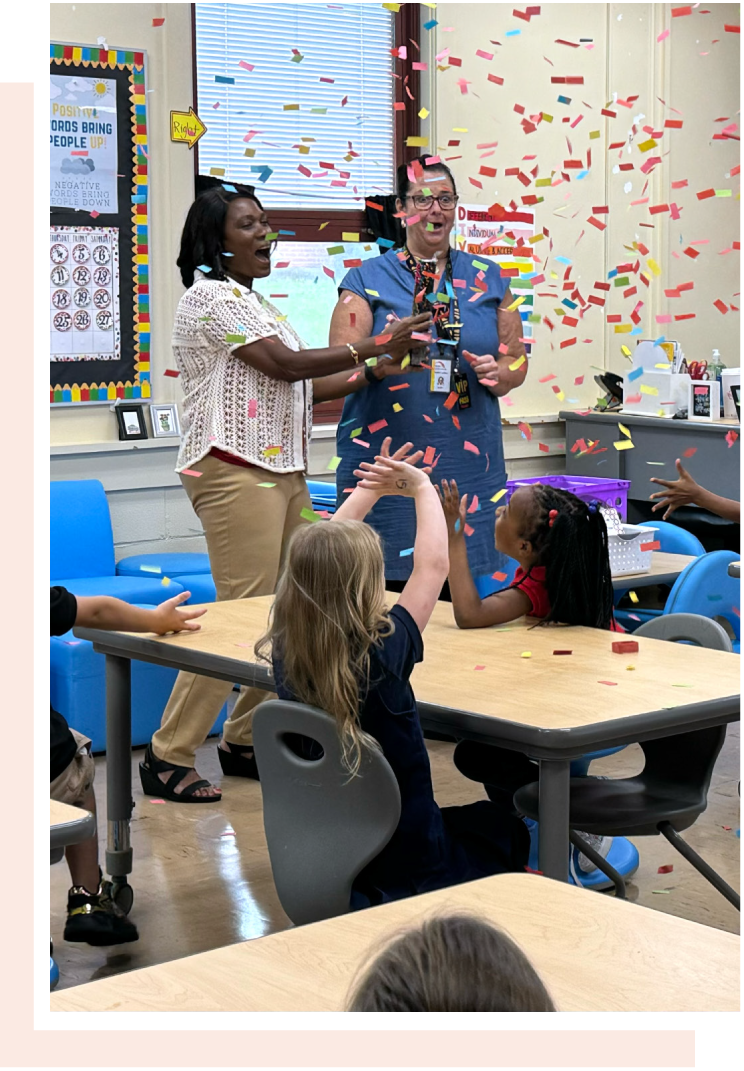

Crucially, the Wraparound Center “is not just for students and staff and parents. It’s for the entire community,” says Desmoulin-Kherat. In the superintendent’s estimation, a positive impact on any member of the Peoria community is likely to make its way back to Peoria’s students—whether directly or indirectly.

“Chances are, our kids are related to whoever is being impacted,” she says. “If we can help someone find a job or get some help, they could be a better mentor or a more encouraging adult. The idea is that strong community schools increase opportunities for everyone—which will then move our community to a state of vibrancy and success.”

Promising to Protect

In 2017, in the wake of President Donald Trump’s executive orders concerning immigration, Desmoulin-Kherat’s school board unanimously passed a resolution to declare PPS a safe haven school district. Citing the landmark Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe—which ruled that states could not deny undocumented children a public education—the resolution committed to making PPS a safe place for “students and families threatened by immigration enforcement or discrimination, to the fullest extent permitted by law.” That meant, among other things, refusing to give immigration officials or other law enforcement access to school buildings “except under certain unique and specified circumstances required by law.”

“It was all about a deep commitment from the board and Peoria Public Schools to create an environment where both students and staff felt supported and protected, especially in times of uncertainty or challenge,” Desmoulin-Kherat says. And now, in 2025, PPS’ most vulnerable families again find themselves in a similar time of uncertainty.

One day into his second term in office, Trump revoked a directive prohibiting Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) from making arrests in “sensitive areas,” such as places of worship or schools. Almost immediately, PPS felt its community react to this federal change. Only a day later, more than 17% of the district’s English learners did not show up to class. So with the support of her board, Desmoulin-Kherat explicitly reaffirmed the district’s commitment to their safe haven resolution.

“With the transition of the new presidential administration and the issuance of several executive orders, many questions have arisen regarding the status of federal immigration policies and enforcement,” she wrote in a community letter dated January 23, 2025. “Peoria Public Schools wants to stress to our families and students that the District is committed to ensuring that our schools remain safe, inclusive, and welcoming places of learning for all students.” The letter also links to the district’s procedures for protecting students’ rights in an interaction with ICE or other law enforcement agencies.

“While the world seems to be caving in on these families, we just wanted to reassure them that the district is here for them, and that we’ll do everything in our power to protect and support them,” Desmoulin-Kherat tells SchoolCEO. The label of “safe haven,” she says, “represents more than just a title for us; it reflects our district’s core values and what we really stand for.”

The City of Gratitude

Throughout all of Desmoulin-Kherat’s work, there runs a common thread: a fierce commitment to—and reliance on—the Peoria community. As she sees it, when schools support the community, the community will support the schools—and together, they can better support kids. All the district’s work, from Peoria GYO to the safe haven resolution to the Wraparound Center, reflects and affirms that belief.

For Desmoulin-Kherat, that mutual support means genuine collaboration. “When I worked at the Tri-County Urban League, other social service agencies would try to ‘collaborate’ with our organization by just asking us to sign off on their proposals,” she says. “We had no input on the concept and no financial benefits. So I learned very early on: That is not actually collaboration.” No matter the situation at hand, Desmoulin-Kherat works to listen, to gather input from the entire community and to share decision-making with as many stakeholders as she can. “We have to include others—all the diverse voices—and that means we may have to give up some power as well,” she says. “This work must be done collaboratively in order to make any significant progress.”

And in her time with the district, Peoria Public Schools has made significant progress—from the alleviation of the teacher shortage to a 15% increase in graduation rates to any of the other accomplishments marking Desmoulin-Kherat’s tenure. It’s no wonder she was named one of four finalists for AASA’s 2025 National Superintendent of the Year, an honor she credits to the entire PPS team and community.

But despite all those victories, the work in Peoria is difficult—and a lot remains to be done. “I have to be passionate and relentless because the work that we do is very challenging,” Desmoulin-Kherat says. “But I’m so grateful that the community is supportive of the work. They realize the challenges, but they also realize the progress.” And true to its name, the City of Gratitude is grateful to Desmoulin-Kherat in return.

“I am inspired to work as much and as hard as I can for the citizens of Peoria because they inspire me every time I see them,” she says. “Whether it’s at the dentist’s office, the grocery store or the coffee shop, someone is always saying, ‘We know you have the toughest job in the city, but keep doing what you’re doing. You’re making a difference.’”

At the end of the day, it’s that relationship between the community and its schools that’s led Desmoulin-Kherat to spend 25 years in Peoria, that brought her home to lead the very first district she ever worked in and that’s kept her there for the past 10 years. “I love this community,” she says—and it’s clear the community loves her back.