This district recovered from a damaged brand. So can you.

How GFW Schools in Minnesota regained community trust—and how you can do the same.

When Dr. Jeff Horton first took the helm as superintendent of GFW Public Schools in July 2020, the district was caught in a downward spiral. The small rural system in Minnesota had just closed one of their three schools and, over time, had racked up a substantial amount of debt. Now operating with a negative 12% unassigned fund balance, GFW was so strapped for cash it was borrowing money just to make payroll.

Getting out of Statutory Operating Debt and actually turning the district around would take time—but Horton and his team only had about six weeks to rescue GFW’s reputation. Just 41 days after his start date, community members would vote on an operating levy that could make or break the district’s recovery. A successful levy would allow GFW to stabilize its finances and work with the community to chart a path forward. But if it failed, the district would face increased class sizes, reduced programming, and maybe even dissolution.

It was clear that in recent years, confidence in the district had waned. Two previous referendums had failed—one in 2017 and the other in 2019—and the first had seen a disapproval rate of more than 80%. How could any district make such a monumental shift in perception in so little time?

GFW’s situation was certainly extreme, but by no means unique. School districts across the nation—maybe even yours—have found themselves with damaged brands for all kinds of reasons, whether it’s a scandal, an unpopular decision, poor management, or something else entirely. But as we’ll discuss, a damaged brand doesn’t mean you’re down for the count.

Listen to your community.

Like so many other issues in education, the path toward fixing a damaged brand begins with listening. You may think you know how your community is feeling about your district and why—but in reality, only they can tell you. The roots of the problem might be more complicated than you think. “A lot of us want to be problem-solvers. We want to find the answer right away and get to work,” Horton says. “But you have to intentionally stay in that listening and processing mode. If you’re not taking enough time to do that, you may miss something important.”

That’s why, in his first 100 days as GFW’s superintendent, Horton spent a huge portion of his time learning from his stakeholders. “Doing listening sessions with the community was one of the biggest things that has led to our success here,” he tells SchoolCEO. “We’ve worked really hard at trying to understand: Where are people on this? Why are they feeling this way?”

This wouldn’t be an easy endeavor in the best of times, but remember: This was the summer of 2020. “We had just closed down schools across the nation,” Horton explains. “So I’m trying to figure out how to get in contact with people during a pandemic.” Despite the logistical difficulty, he knew this was a step that couldn’t be skipped. He set up several meetings on local farms with lots of outdoor space for social distancing. “We’d get into these massive circles, trying to have conversations,” he tells us.

Through sessions with a wide range of groups—from farmers and business owners to legislators and the media—Horton got a handle on GFW’s story as it existed then. He says he can distill most of the perspectives he heard into two major themes. The first? Confusion. GFW hadn’t always faced the troubles it was dealing with in 2020; in 2010, they’d been a trailblazer, introducing one-to-one iPads to their high school students far ahead of the national trend. “That’s a district that says, We’re innovative. We’re ahead of the curve,” Horton tells us. “But not even a decade later, we’re looking at possible dissolution because finances are in disarray—and people are wondering, How did we get here? How did we go from a place with so much pride and success to this?”

Was it difficult to hear all that confusion, hurt, and criticism? Absolutely. “But if you as a superintendent aren’t willing to walk into a room full of people who don’t agree with decisions that have been made, who else is going to do that job?” says Horton. “It’s important as a leader to go out there and talk with people who are critical of you or your organization. Their voices are still extremely important, and if we don’t take time to understand why they feel the way they do, it’s really hard to move people forward.”

But Horton also heard undercurrents of something encouraging: hope. “People wanted a reason to believe,” he says. “Despite the frustrations, despite the hurt, most people were looking for a path forward: How do we get out of this? How do we get back to what once was?” Fortunately, Horton would be able to tap into that hope as he built buy-in for the levy and worked to restore his community’s trust.

It’s important to note: Listening isn’t a one-time task. If you want to pull your district from struggle to success, you have to keep that conversation going. In these early listening tours, Horton promised his community that he and the district would keep listening as they put potential levy funds to use and created a new strategic plan. “We told them, If we pass this, we will invite the community in, gather your input, and define what our future looks like together,” he says.

These listening sessions did more than just provide Horton and his team with crucial insights. They also played a pivotal role in rebuilding the community’s trust in its schools. “Our community values hard work,” Horton says. “When they saw us working that hard to understand and listen, I think that was a step in the right direction.”

Whatever circumstances have damaged your district brand, listening to your community is the best way to start moving forward. Hearing their specific thoughts, fears, disappointments, and hopes will show you what misunderstandings need clarification and what mistakes need rectifying. And just as importantly, it will assure your stakeholders that their schools are in the right hands.

Address stakeholder needs.

Once you’ve taken the time to listen to your community, you essentially have a game plan for moving forward. You understand where your stakeholders are coming from and can therefore respond to their specific concerns, rather than addressing issues that may not actually matter to them. “In order to listen to you, people have to connect with the story you’re telling,” Horton explains. “If you don’t understand your audience, you can’t tell a good story. That’s why listening as a superintendent is so important.”

At GFW, Horton knew that to win stakeholders over, he had to address the confusion he’d heard in these community conversations, and that started with explaining the district’s financial situation. Understandably, stakeholders were concerned about the district’s debt. In the absence of clear information, a damaging story had emerged: GFW isn’t a good steward of our taxpayer dollars.

But the real story was more complicated than that. At least part of the district’s financial troubles came from their commitment to special education. “The federal government currently does not fund at the level that they promised when IDEA [the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act] was passed as legislation,” Horton explains. “The states aren’t fully funding special education either, so that falls to the school districts and the local tax.” But under IDEA, students with disabilities must receive the services they need, no matter what it costs. This puts many districts—including GFW—under significant financial strain.

As a former special education director, Horton knows the importance of this work. “I believe the things we’re doing are right, but they do have a cost,” he says. “People wanted to know why the district finances were where they were, and that’s not the only reason—but it is a piece of it.” When the district provided that clarification in informational meetings about the upcoming levy, it resonated with their community.

But GFW’s stakeholders also needed to see the district holding itself accountable. “We had to own some things,” Horton tells us. “As the new superintendent, even though I wasn’t here when this all started, I still needed to own up and say: You’re right—we made some mistakes. Here’s what we could have done better. We hear you, and we’re going to act on that.” And while he couldn’t take much action in the 41 days before the vote, Horton did promise the community that, should the levy pass, the district wouldn’t use any of those funds until they had exited Statutory Operating Debt. The levy wouldn’t be a bailout; it would be an investment in the district’s future.

Just by communicating with his stakeholders and responding to their perceptions of the district, Horton was able to course-correct GFW’s reputation in the community. Where local stakeholders had once seen poor stewardship, they now saw tough decisions and a renewed commitment to accountability. “My story for the district wasn’t necessarily new,” Horton says. “It came from the community’s view of the district, but we were able to focus it into something that acknowledged where people were, touched on hope, and then offered them a path forward.”

Find your why.

Listening to your stakeholders and addressing their needs will put you well on your way to rebuilding your community’s trust—but achieving true success will take some significant refocusing. To fight your way back, you’ll need to know what you’re fighting for.

On August 11, 2020, GFW’s operating levy came to a vote. It passed with more than 60% support. In an incredibly short amount of time, Horton and his team had managed to regain a great deal of community trust. “I think that’s the highest operating levy that has ever passed in our community,” he says. “That tells me that people want a district here and they believe in the district.” But what would be GFW’s rallying cry moving forward?

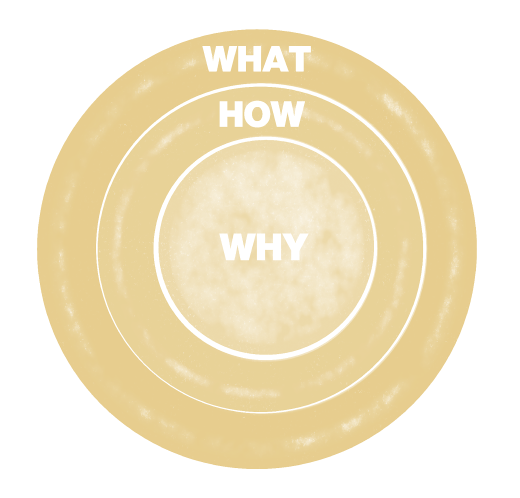

Horton had once come across a TEDxTalk by author and motivational speaker Simon Sinek, describing what he called “The Golden Circle.” Sinek starts with a question: Why do some people achieve greatness when others—even those who have all the same talents and resources—don’t?

In Sinek’s mind, the answer is simple. “Every single person, every single organization on the planet, knows what they do,” he says. “Some know how they do it ... but very, very few people or organizations know why they do what they do.” For Sinek, that why is the key difference between the ordinary and the great. “What’s your purpose?” he asks. “Why does your organization exist? Why do you get out of bed in the morning? And why should anyone care?”

“I think that was what we were searching for when I first started,” says Horton. “We didn’t have a why. We’d lost it. The district was in survival mode, and why wasn’t even on their radar.” But refocusing on that purpose would be critical as they began building a new strategic plan.

True to their word, GFW began the process by reengaging their stakeholders. “We did equity diagnostic surveys, we did community surveys, we did another round of listening tours,” Horton says. “We put together focus groups and planning groups.” At every turn, they asked their community for input. But amongst the more nitty-gritty questions, the most important was also the most basic: Why do we do what we do? What’s the district’s reason to exist?

Horton already had an idea of his own personal why. “I believe that we need to challenge the status quo of education,” he tells us. “We need to rethink how we are serving students. If we’re seeing 3% drops in enrollment across the country, why are we seeing that? What is making families feel like public education isn’t doing what it needs to do? I’m pro-public education all the way—but we have to take a good look at ourselves and ask, How are we challenging ourselves to get better?”

In one of these meetings, someone—not Horton, as he’s quick to admit—hit upon the perfect summation of this idea: Growing Future World-Class Leaders. “At the end of the day, you have to remember that you are here to serve students and to help students be successful,” he says. “For us, that’s growing future world-class leaders. Once we hit on that, we could start looking from the inside out of that circle: How do we do that? And what do we do? Everything we have done since has been based on that idea. It’s pushed us to ask: How are we still challenging the status quo?”

As you rebuild your brand, you need to find your why. Maybe, as at GFW, your why is growth and constant improvement. Maybe it’s building up your community or producing kind and intelligent citizens. Whatever it is, your why is your motivation—and you’ll need it in order to keep up the good fight.

Follow through.

As so many school leaders know, trust is hard to win and easy to lose. If GFW let the community down again after this vote of confidence, the damage to the brand—and the district’s future—would be nearly irreversible. In short, the pressure was still on to build and keep stakeholder trust. It was key to follow through on the promises they’d made before the vote.

And that’s just what the district did. With guidance from financial services companies Baird and PMA, GFW implemented a plan to allocate its budget more efficiently. They worked with their community to successfully develop and implement a comprehensive strategic plan. Just two years later, the district had exited Statutory Operating Debt and achieved a projected positive 12% unassigned fund balance—all before spending a single dollar from the levy.

These days, GFW is thriving. Through a Comprehensive Literacy Grant, they’ve provided coaches to assist elementary school teachers with literacy instruction, improved classroom libraries, and hired a family literacy specialist to engage families in the joy of reading. They’ve boosted their support for English learners and renewed their focus on social and emotional learning. Class sizes are down, and the district is now offering over 100 new courses and opportunities for students. It’s a complete 180.

Now, after hitting rock bottom, GFW has come back stronger than ever. “I wouldn’t wish Statutory Operating Debt on anyone,” Horton says. “That was very hard for our community. But sometimes, you take things apart in order to put them back together the right way.”

If you’re trying to regain your community’s trust or rehabilitate your district brand, don’t give up. It may be difficult at first, but if you let your why guide you, you’re bound to make a comeback.

Originally published as "Making a Comeback" in the Spring 2023 issue of SchoolCEO.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!