Be the Backup

Helping your teachers thrive in trying times

Just a few short months ago, teachers were being lauded as superheroes. As educators faced school closures, adapted to online instruction, visited students in teacher parades, and even handed out meals to families, the country saw a nearly unprecedented boom in teacher appreciation.

In April, a survey of 2,000 parents conducted by educational STEAM brand Osmo indicated that 80% had gained a newfound respect for teachers during the pandemic. After helping their kids through online learning at home, 69% said they thought being a teacher was harder than their current job. Even teacher pay became a hot topic; 77% of parents surveyed said teachers should be paid more. TV mogul Shonda Rhimes took to Twitter in March to express her own appreciation: “Been homeschooling a 6-year old and 8-year old for one hour and 11 minutes,” she writes. “Teachers deserve to make a billion dollars a year. Or a week.”

But as some teachers pushed to continue remote instruction in the fall, the public narrative surrounding educators began to change. Suddenly teachers were selfish, lazy, even cowardly. “No other group has shown as much contempt for its own work during the coronavirus crisis as teachers,” says conservative writer Rich Lowry in an opinions piece for the New York Post. “Doctors, health workers, cops, and firefighters have all put their lives on the line… [Teachers’] first and last thought has been of their own interests. They have sought to limit their labor while still getting paid—at the ultimate cost of the education of kids.”

You’ve probably heard this sentiment echoed in your own communities over the last few months. In some ways, it’s a natural response to the unprecedented situation we find ourselves in. “An early stage of grief is to be in a state of anger,” explains Dr. Christina Cipriano, Assistant Professor at the Yale Child Study Center and Director of Research for the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. “There’s so much to be angry about these days. Many of us continue to be angry at all the loss we are experiencing right now—not only the loss of life, but loss of experiences, interactions, routines, and careers.” And our teachers, she says, are “just there”—an available target for all that anger.

So now, even well into the school year, many of your teachers find themselves caught between a rock and a hard place. If they’re working from home, they may be facing the disdain of some parents on top of the myriad challenges of distance learning. And if they’re teaching face-to-face, they could be dealing with heightened anxiety, attempting to keep learning at its highest levels while keeping students—and themselves—safe. Facing all these challenges, your teachers may be at greater risk than ever of burning out.

Teacher stress is worse than ever—but it’s also nothing new.

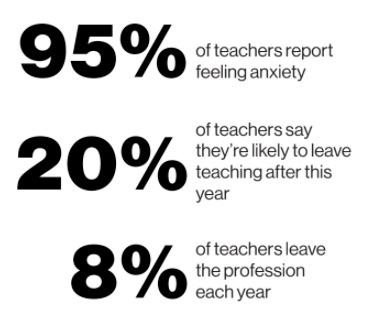

For many teachers, the struggles brought on by COVID-19 have been the hardest of their careers. At the end of March, just as the pandemic began, the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence (YCEI) and the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) surveyed 5,000 teachers nationwide about their emotional states. Their most-mentioned emotions were anxious, fearful, worried, overwhelmed, and sad; a staggering 95% mentioned anxiety.

The stress of the current moment may even be driving many teachers from the profession altogether, potentially aggravating an already dire teacher shortage. In a May Education Week survey of 1,907 teachers across the country, 20% identified themselves as likely to leave teaching after this year; only 9% had planned to leave before COVID-19 hit. What’s more, 44% say their colleagues are more likely to leave teaching now than they were prior to the pandemic.

But COVID-19 isn’t just creating a new set of obstacles and stressors for teachers; it’s exacerbating problems that already existed. In 2017, long before the pandemic, the YCEI conducted nearly the exact same survey of teachers and their emotions. Even then, the feelings identified were overwhelmingly negative. The top four were frustrated, overwhelmed, stressed, and tired—not so different from this spring’s results. As Cipriano writes in a summary of the research for EdSurge, “the primary source of educator frustration and stress pertained to not feeling supported by their administration around challenges related to meeting all of their students’ learning needs, high-stakes testing, an ever-changing curriculum, and work-life balance.”

That frustration and stress has been reflected in turnover patterns. According to an Education Week analysis, all 50 states experienced statewide teacher shortages in at least one subject area in 2018—and those numbers are only set to get worse in the aftermath of COVID-19. Data from the Learning Policy Institute suggests that 8% of teachers leave the profession every year, pandemic or not.

So yes, your teachers are facing incredible challenges in the current moment. But as you probably know, they were already stressed. Throw in learning an entirely new mode of teaching, trying to help their own kids with online school, or even putting their health on the line for students, and it’s no wonder that some teachers are at their breaking point.

This is a huge problem—not just for your teachers themselves, but for your district. As the teacher shortage rages on, you can’t afford to lose your staff. That’s why it’s incumbent upon you, as a superintendent, to provide your educators with genuine, effective support. Doing so will take effort and resources, but investing that time and energy now can boost your teacher retention and keep your schools thriving long after we’ve gone back to normal.

If you’re not sure where to begin, never fear. Talking to the leading experts on teacher retention and social-emotional health, we’ve compiled the best tips we could find for making your teachers feel valued, supported, and prepared to deal with their current circumstances. You worry about supporting your teachers; we’ll support you.

Support your teachers’ social and emotional growth.

When we think about social-emotional learning (SEL) in the education space, we’re often focused on kids. More and more, schools are adopting SEL into their curricula, teaching kids to understand and regulate their own emotions right alongside multiplication and division. But to experience the kind of social and emotional growth needed to deal with traumatic situations like COVID-19, adults need to practice and master these skills as well.

At the YCEI, Cipriano and her research team “have always invested in teachers first” when it comes to SEL, she tells us. Our emotions are linked to so many aspects of our lives: attention and memory, decision-making, job performance, relationships, and our health. It’s very difficult to teach effectively—especially right now—without the skills required to handle intense emotions in a healthy way.

“Educators need to be able to show up as their whole selves in their classrooms, especially during this sensitive time in our lives,” Cipriano tells SchoolCEO. “If we as adults aren’t able to regulate our fears and anxieties effectively, those feelings will undermine our ability to be emotionally available to our students.” That, in turn, could aggravate students’ own emotional difficulties, she says. “Our fears are going to manifest in the way that we engage with our students and children, which will impact how they, in turn, interact with us. We need to authentically express our emotions for our children, and provide them with a safe and welcoming learning environment where they can share their fears and frustrations.”

And teachers with emotional skills don’t just create healthier classrooms; they build healthier lives for themselves. YCEI’s research has found that the more a teacher develops their emotional skills, the more satisfied they’ll be in their job. Teachers who have practiced and internalized SEL are less likely to burn out.

Of course, SEL is a complicated topic, one we can’t cover comprehensively in a single article. Right now, you can find several resources and programs online—many of them free—to help your teachers build their emotional skills. But to be successful, you need to provide your teachers with more than the resources themselves. They also need tangible support from you.

Commit to social-emotional learning as a leader.

The success or failure of your teachers’ social-emotional learning largely depends on you. If you’re not modeling what you expect your teachers to learn, it’s unlikely to stick.

“When leaders are not bought into social-emotional learning implementation, it does not get implemented with fidelity,” Cipriano tells us. “It takes more for the leader than to find the time and send the link; they need to go through it, too. They need to be in the narrative, have the experience, then model it in how they’re engaging with their school community.”

But the opposite is also true, according to YCEI’s research. When administrators have developed emotional skills, teachers tend to have more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions. Just as a teacher’s emotional health affects their classroom environment, your emotional health as superintendent affects the entire district you lead.

So as a school leader, you need training in SEL, too. Cipriano’s advice? “Invest in a program or an approach alongside a learning community,” she says. Many online SEL trainings group participants in cohorts, giving them a group to connect with and learn from. In particular, the RULER Approach to SEL, offered by the YCEI, centers on investing in adult SEL training first. “You can only get so far personally on Google,” Cipriano says. “Going through systematic SEL training as a cohort—especially as we’re going through this pandemic experience—and finding those connections is going to enable sustainable success, long after the crisis of the pandemic has passed.”

Grant teachers the time and space to work on their emotional skills.

Giving your teachers SEL—something meant to reduce their stress—will be pretty useless if it just becomes one more thing on their to-do list. If you really care about your educators’ emotional well-being, you need to offer them (and yourself) the time and space in their workday or week to actually do that learning. It’s a hard ask, we know, especially when teachers already have so much on their plates. But prioritize it. With better social-emotional skills, your teachers will be less stressed, more engaged with their students, and less likely to burn out—all of which make them more likely to stay in the profession.

According to Cipriano, investing the time and resources to provide SEL for your teachers can pay immeasurable dividends to your district—especially during a global pandemic. “Thinking about the disproportionate impact of the pandemic and the compounding traumas of the time—when SEL is implemented systematically with an evidence-based approach, it can help to support those pieces as well,” she says. “SEL is not the Band-Aid for the pandemic. But it is an onramp to school community resilience and thriving, now and in the long term.”

Give teachers more voice.

As a Professor of Education and Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Richard Ingersoll has spent his career studying the teaching profession, from patterns in recruitment and retention to the causes of nationwide teacher shortages. When we spoke to him in 2019, long before the pandemic began, he emphasized the importance of giving your teachers autonomy and input.

“The data has long shown that a key factor in teacher retention is the issue of voice: how much input and say teachers have into the key decisions that impact them and their jobs,” says Ingersoll. “Teachers often have very little voice; school systems are often run in a top-down manner. The people on the ground get frustrated with all kinds of reforms and mandates that come down the pike where they’re not consulted. It’s things done to teachers as opposed to with teachers.”

Decisions at the district level are affecting your teachers’ lives, not only professionally, but also personally—especially now. “The lack of autonomy was significant before the pandemic,” says Cipriano, “but now it’s coming up in different ways. Due in part to the rapid rate of change across the demands on the education system, educators are not being involved in the decisions being made.”

You may not be able to bring your teachers into all your decisions right away, but you can take small steps now toward including their voice and affording them greater autonomy.

Build an Emotional Intelligence Charter.

To make sure you’re considering your teachers’ feelings and needs as you make decisions, Cipriano and her colleagues at the YCEI recommend building what they call an “Emotional Intelligence Charter.” This will be a living document in which leaders and teachers can work together to agree upon how you all want to feel about work, and how you will behave to achieve those feelings.

To build your charter, begin by asking how all your teachers want to feel at work. Try to narrow it down to a top five that you feel represents the whole faculty. Then, work through that list, asking for specific, actionable ideas as to how you can create those feelings in the workplace. For example, say your teachers want to prioritize a work-life balance, especially if they work from home and those lines blur. “If you want to set boundaries, set them together,” Cipriano suggests. “Commit to how often you’re going to check your email, or what should be the norm for response rates. That way, you aren’t feeding into a system where everyone is continuously overtaxed and under-resourced.”

Building an Emotional Intelligence Charter allows teachers some say in what’s expected of them—and also offers the opportunity to share what they expect from you. Rather than coming up with top-down solutions to the stresses and challenges your teachers are facing, you can work together with them to find the most effective paths forward.

Let teachers drive their own professional development.

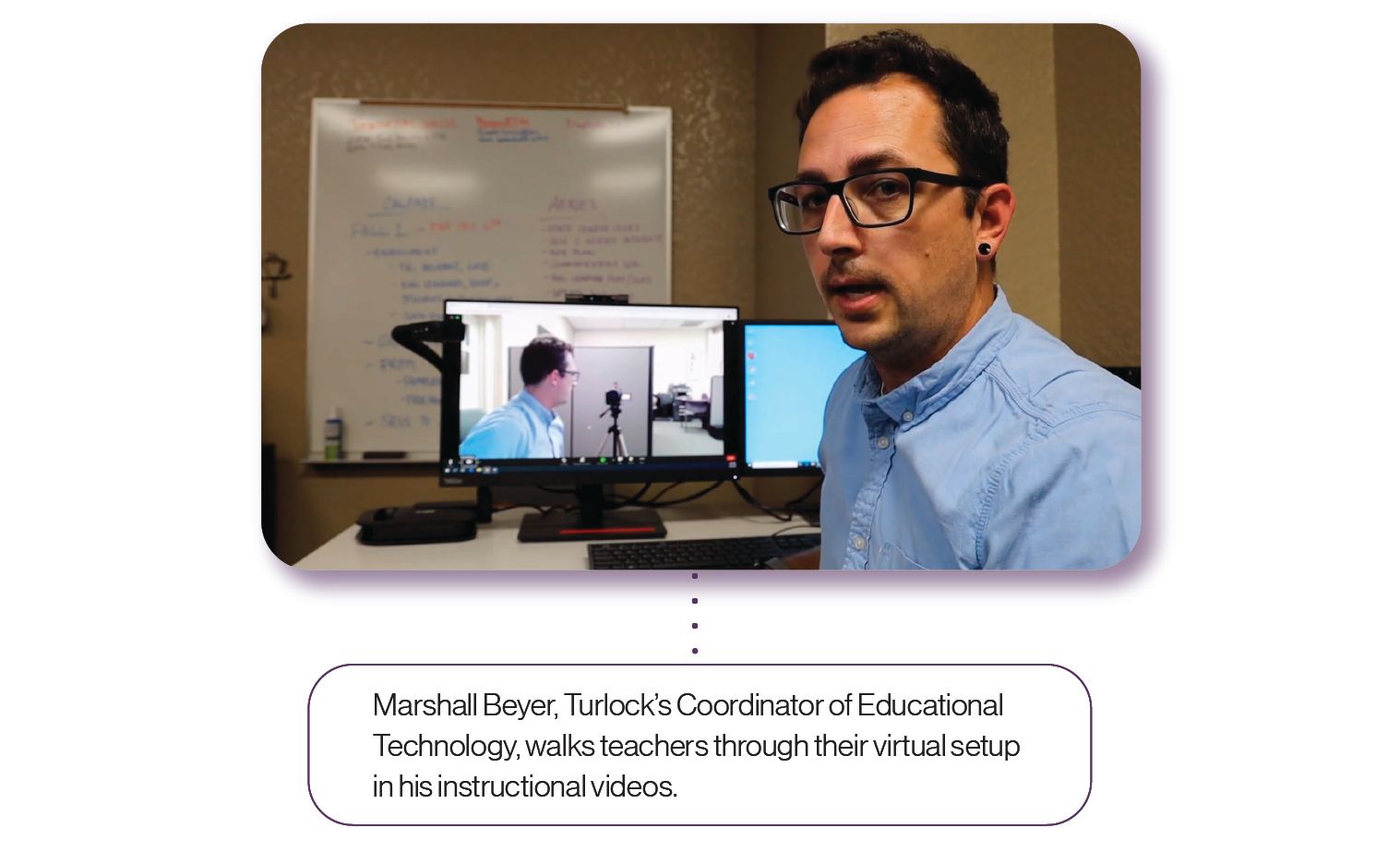

As California’s Turlock Unified School District closed its doors in late March, Marshall Beyer and Sitara Ali knew they had their work cut out for them. Beyer, the district’s Coordinator of Educational Technology, and Ali, an Educational Technology Instructional Coach, set out to create effective, virtual professional development for their teachers—as quickly as possible.

“Sitara and I knew the makeup of our teachers,” Beyer tells us. “We knew that there was a group that had some tech savviness, but there was a big group that didn’t. We needed to do something for those teachers.”

Just a week after Turlock closed, Beyer and Ali began releasing their first professional development series for teachers. But instead of telling the teachers what they should be learning, they asked teachers what they wanted to know. “A lot of it was based on teacher feedback,” Beyer explains. “We would ask them what they wanted, take that feedback, and put a PD together.” Sessions covered everything from engaging students over Zoom to building a Bitmoji classroom—whatever teachers were interested in.

Teachers could also choose how they consumed the information Beyer and Ali shared. They could watch video presentations, listen to an audio podcast version, or simply look at slides and handouts—whatever helped them learn best. “There’s all these different modes in which students learn, whether it’s visual, auditory, or something else,” Beyer explains. “We wanted to provide those for teachers as well.”

The choice of whether to participate fell to the teachers themselves as well. The sessions weren’t mandatory. “We felt that giving teachers that choice of whether to attend or not put it all in their hands,” Ali says. “Some teachers, especially our new teachers, don’t need that extra help to learn how to navigate those tools.”

Virtual professional development turned out to be a smashing success—so much so that teachers are clamoring for more. “Even before school started, when our district announced that we would do distance learning, teachers were reaching out to both of us asking for more training,” Ali says. Beyer credits that positive reaction to the fact that Turlock’s professional development put teachers in the driver’s seat. “We also found that when we made it about things that they wanted, we were getting more buy-in,” he says. That principle, he says, carries over into the classroom environment. “We were trying to translate that to teachers: When you are creating assignments and you’re giving your students choice, they’re going to be bought in more, too.”

Beyer and Ali told us that even when the pandemic ends, they’re likely to continue providing professional development online—precisely because it gives teachers so much control. “Our teachers deserve that flexibility,” says Ali. “They have kids at home. They have lives. They need to be able to choose when they learn best as well. Some are better in the morning, some are better in the evening. Some are better when they wake up at 2 a.m. with their new baby. It depends on what works for them. We will keep our virtual PD series going because it fits everyone.”

Provide opportunities for feedback and self-reflection.

Nearly every source we talked to gave us some variation on the same phrase: This year, every teacher is a first-year teacher. As many teachers continue to adjust to online instruction, others are struggling to manage an in-person classroom full of masks, plastic shields, and other (potentially distracting) protective elements. Still others are working with hybrid models, trying to teach online and in-person students simultaneously. Many are wondering, Am I even doing a good job?

“I think teachers are really, really tired, and they’re working harder than they’ve ever had to work,” says Dr. Mary Ann Wolf, President and Executive Director of the Public School Forum of North Carolina. “But I don’t know that they’re often getting that feedback to know what’s working.” Teachers need feedback, not only to affirm their hard work, but to help them improve in this new environment.

The strategy Wolf recommends is deceptively simple: if you want feedback, just ask. “School districts can survey parents and students just to see how they’re doing, what’s working well and what’s not,” she tells us. “I often think that kids might go along with things and not really voice frustrations they’re having, especially high school kids. Surveying families, but especially students, can be really helpful.”

But, as Wolf points out, “you do have to ask.” You can’t just expect your students or parents to provide unsolicited feedback—especially in such a chaotic time. “No matter who’s doing the asking—whether it’s the teacher, the principal, or the superintendent—if we don’t ask questions for feedback, we might not get it,” she says.

You can also provide feedback from within your district, adapting structures you might have used pre-pandemic to our new reality. “In a school setting, principals, coaches, and other teachers can engage in learning walks: going into a classroom not to evaluate, but to learn and have a discussion about what they saw,” Wolf says. “That is possible online. It just feels different. In some ways, it’s almost easier online; you can quickly Zoom into a classroom and see how things are going.”

Long before the pandemic, entrepreneur Adam Geller had the same idea: Wouldn’t feedback for teachers be easier in an online space? “We know the best way to help teachers get better is through direct feedback on their actual teaching,” Geller tells us. “That’s what the research says. And the thing holding that back from happening in a K-12 school setting is that it’s really hard to have the right person in the right place at the right time.” That idea inspired Geller to create Edthena, a platform which allows teachers to film and share their instruction with colleagues, coaches, or administrators for timestamped feedback.

Crucially, catching a lesson on video also allows teachers to watch themselves at work, affording a unique opportunity for self-reflection and analysis. Geller illustrates this through an anecdote he heard from Laura Baecher, a researcher at Hunter College. “Imagine if teachers were artists, and we told them all about their brushstrokes, about the feeling that their painting evoked, about what we took away from it—but we never showed them the painting they made,” he explains. “That’s essentially what we’re doing when we go in to observe a teacher. We’re telling them all the things that we see, but we aren’t letting them see what is happening in their classroom environments.” When teachers can watch themselves teaching, they can see the work of art they’ve created—and how they’d like to change it.

As teachers fight to adapt an uncertain, unfamiliar circumstance, feedback is even more crucial than before. Your educators need your help finding avenues for feedback—whether from you, your community, or themselves.

Uplift your teachers to your community.

You know better than anyone that despite the negativity some in your community may feel, the vast majority of your teachers are giving their all. You’ve seen them working long hours to adapt lesson plans, taking on extra training to learn new technology, and paying for hand sanitizer and masks out of their own pockets. No matter how public opinion has changed since March, teachers are still superheroes. So it’s up to you to convey that to your district community.

At Highline Public Schools in Washington, the communications team has been working hard since the spring to make sure teachers get the recognition they deserve. “We started right away when COVID happened,” says Tove Tupper, Assistant Director of Communications. “When you say schools are closed, it gives the impression that nothing’s happening. But in reality, it’s only the buildings that are closed. That doesn’t mean our teachers aren’t working and our students aren’t learning. We really wanted to make sure that came to life on our social media.”

Highline is making special use of Instagram. With the hashtag #HighlineAtHome, they share photos of educators in their own houses, showing their online teaching in action. The district also gives the school community opportunities to uplift their educators. For this year’s Teacher Week, the Highline team highlighted outstanding teachers and their accomplishments, as told by their principals and peers. Students and families got in on the action through Instagram stories, where a question box asked them to shout out their favorite teachers.

When the YCEI conducted that initial survey of teacher emotions in 2017, they also asked teachers how they wanted to feel. Among the top answers were valued, supported, effective, and respected. Every day—but especially right now—you should be working to instill those emotions in your teachers. You should be helping them grow as people and professionals, supporting their ideas and decision-making, and making sure your community sees their dedicated work. It’s a hard time for your teachers, but they’ve always had a harder time than most. Now it’s up to you to make their jobs a little easier.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!