Survey: The Great Distance Learning Experiment

Over 1,200 parents across the country tell us the ups and downs of learning from behind the screen.

As you well know, the rollout of distance learning wasn’t anticipated. It wasn’t organized, and there wasn’t the time or funding to properly test out this new system. The emergency solution to school closures was just that—a stopgap created in response to an unprecedented crisis.

But even though districts didn’t have the time to perfect their remote learning experiences last semester, the situation still opened a proverbial Pandora’s box. Households across the country have been introduced to a significantly new

schedule and method of instructional delivery for K-12 education—and those experiences can’t be put back into the box. For better or worse, school closures have functioned as an important test of distance learning.

There’s an opportunity for COVID-19 to speed up innovation, enabling rapid changes and growth in school systems across the nation. So we wanted to know what K-12 parents thought of remote learning during the Spring 2020 semester. Did the model fit in with families’ lives and students' aptitudes? What was most appealing about online learning, and what was most challenging? What did parents learn about their students, their teachers, and their children’s

educational opportunities?

In March of 2020, we surveyed a diverse set of over 1,200 parents from across the country. Respondents represented rural, suburban, and urban schools; reflected a range of income levels; and had students in grades K-12 (see Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Using participants’ answers to both multiple choice and open-response questions (Answers have been edited for grammar and clarity), we’ll summarize key insights we collected from parents as well as their advice for school leaders on improving the distance learning process.

How did it go?

Overall, most parents were dissatisfied with their online learning experiences. We asked, “How attractive is the idea of online or blended learning now that you have experienced it firsthand?” with responses ranging from “significantly more attractive” to “significantly less attractive” (see Figure 5). Around 47% of parents selected “less attractive” or “significantly less attractive,” with 22% indicating “no change.” Still, a notable 31% of parents found the system more attractive.

The disaggregated data offers a more complete picture. Parents in urban areas found distance learning more attractive than suburban or rural parents. The number of children in each family made a difference as well; the more children a parent had, the less attractive they found online learning.

Generally, this question breaks families into three groups—a large group for whom online learning is either impossible or unattractive, a handful of parents ready to work online permanently, and a neutral group of parents interested in improvements in the system. Each group provides different, critical insights into the system’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement.

For many families, remote learning isn't an option.

Distance learning in its current state just isn’t feasible for some households. Many parents work during the day and are unable to be fully involved in their children’s virtual learning—or simply aren’t home to care for their kids. A few parents wrote that their student needed a paraprofessional during the day; without their help, learning wasn’t possible. In some households, there simply isn’t the time or capacity for learning to occur with kids at home, which disproportionately affects some of the nation’s most vulnerable children.

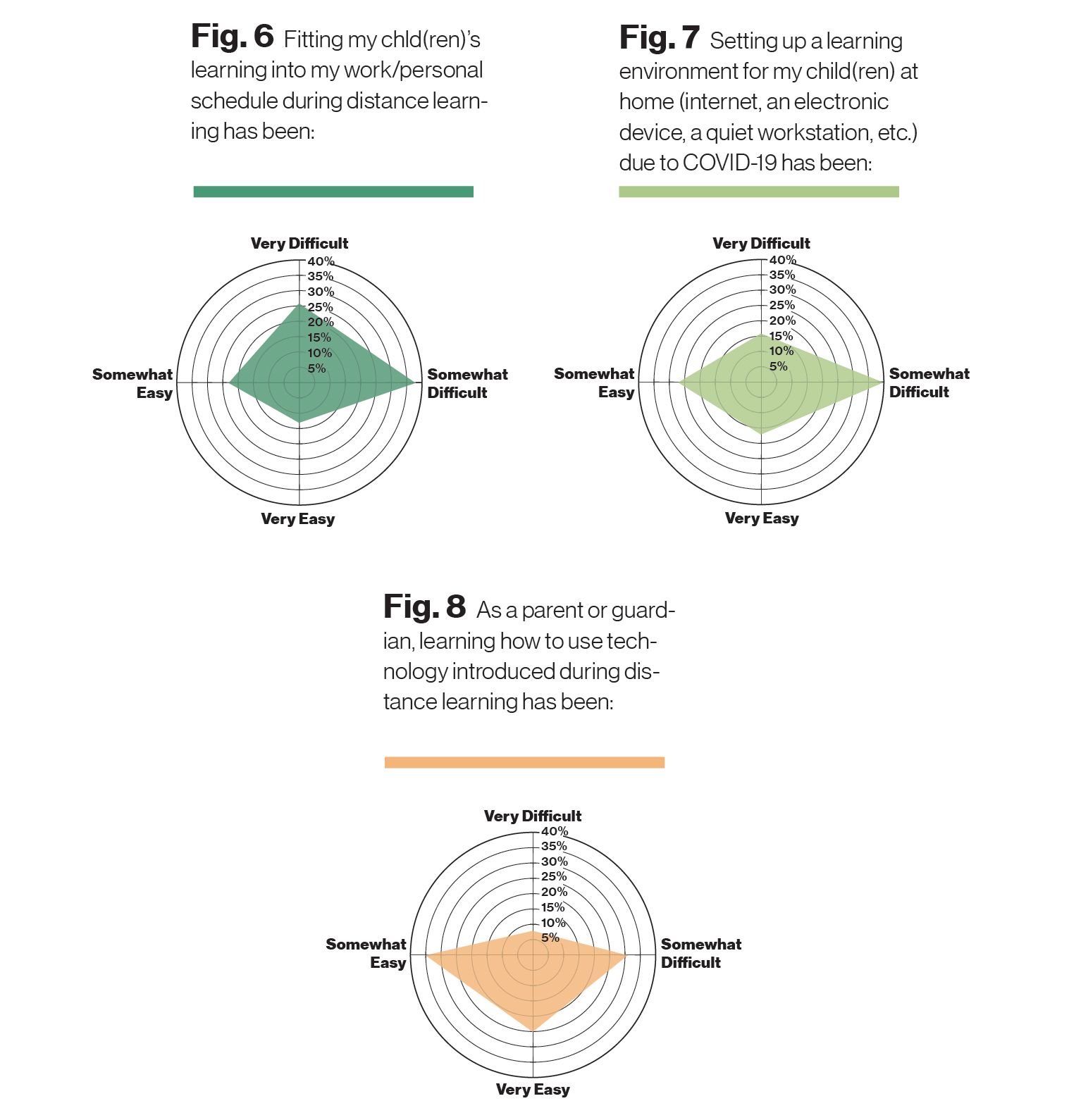

We asked respondents to finish the sentence, “Fitting my child(ren)’s learning into my work/personal schedule during the switch to distance learning has been...” with a range from “very difficult” to “very easy.” Around 64% of parents indicated that online learning did not fit in with their schedule by marking “somewhat” or “very difficult” (see Figure 6). Only 13% marked that it was “very easy,” while 23% expressed that it was “somewhat easy.” What’s more, responses were similar across income levels—even wealthier parents struggled to fit distance learning into their schedules.

Setting up a learning environment—internet, an electronic device, a quiet workstation, etc.—was also a challenge. When completing the sentence, “Setting up a learning environment for my child(ren) at home due to COVID-19 has been...” with the range mentioned above, a little more than half of folks indicated difficulty; 16% marked “very difficult” (see Figure 7). Not surprisingly, the ease of setting up a work environment for students varied by income. Higher-income parents were more likely to indicate that this was “very easy” or “somewhat easy.”

What’s more, technology tended to pose a greater challenge for lower-income families than for higher-income ones. Parents completed the following sentence with responses ranging from “very difficult” to “very easy”: “As a parent or guardian, learning how to use technology introduced during distance learning has been...” (see Figure 8). For the most part, parents seemed to adjust well; around 60% indicated that learning to use pertinent technology was either “somewhat easy” or “very easy.” But again, disaggregating the data tells a more complex story. Higher-income families had less trouble learning the technology used for distance learning, perhaps due to increased access to higher-quality devices—and technology in general—before COVID-19.

In many districts, these challenges exacerbate systemic problems. Some, like Georgia’s Chattahoochee County School District, ended distance learning early due to complications with their system, while others faced delays in getting their online learning systems up and running. Of course, these challenges disproportionately affect districts with lower funding as well as more vulnerable students. One district in Pennsylvania began online learning more than 40 days after schools closed, placing the district’s students—90% of whom are children of color, and three-quarters of whom live in poverty—weeks behind their suburban peers.

What did parents like most about online learning?

After last semester, only a handful of respondents came away from their distance learning experience as advocates for the new system. However, parents across the board noted its benefits. While not all parents are ready to permanently switch their child’s mode of learning, their comments reveal weak points in the traditional K-12 structure that are remedied online.

Most prevalently, the switch to online learning seemed to present a welcome change of pace. Working from home cut out the dreaded commute, creating a more relaxing atmosphere for students to work at home with family. For many parents who started working from home during COVID-19, distance learning meant more time with their children. And with less time in class, students could work at their own pace, either allowing for extra free time or more time to work through problem areas in the curriculum.

When asked the open-response question, “What do you and your child(ren) like most about distance learning?” around 32% of respondents made some reference to their students’ comfort and well-being: waking up later, spending more time together at home, having less hectic mornings (see Figure 9). “I like having my kids home with me,” wrote one parent. Another mentioned “the ability to be at home together more with some flexibility as to when the learning takes place. We also did not need to start as early so my kids got more sleep.”

“More sleep” and “no commute” were some of the most common answers. These types of logistical responses may not seem significant, but the frequency points to a real appreciation for a relaxed routine throughout the school year.

Flexibility was the next significant category at around 16%; answers highlighted positive factors like flexible hours. “My son liked that he could get his work done in half the time and still make good grades, since he doesn’t need all of the allotted class time,” explained one respondent. The flexibility in pace also proved beneficial for kids who need more time with the material. “We both appreciated that my child could take his time to complete his work,” said one parent. A few respondents mentioned flexibility as a benefit to children with disabilities. (Generally, however, parents of students with disabilities were quick to point out cracks in the distance learning model.)

The third most popular response captured a vocal group displeased with distance learning; around 15% of respondents actually wrote in the word “nothing” or a similar phrase. “Nothing,” sums up one parent. “They hated not being with their friends and favorite teachers. It made it hard on us parents to find the right amount of time to get everything needed done, because they were given a lot of work.” For comparison, less than 1% of respondents wrote “everything” or a similar answer.

Only around 5% of parents noted something related to the creative structure of distance learning, such as Zoom calls or innovative online course content. One parent liked “the outside-the-box learning on how to access materials, people, and support electronically.” For around 6% of respondents, though, the best part of the distance platform was simply safety—most responses to this effect were related to COVID-19, but some also referred to bullying at school.

The last significant segment of respondents—around 6%—enjoyed having a greater role in their child’s learning when working from home. “I love being able to have hands-on knowledge of what my children are learning,” wrote one respondent. Learning remotely allowed some parents to focus on areas where their child was weakest—“I like being nearby to help them faster with any learning concerns,” wrote another parent.

In a separate portion of the survey, parents were asked to finish the sentence, “During distance learning, I understand what my child(ren) is/are learning...” with answers ranging from “significantly more” to “significantly less” (see Figure 10). The results are somewhat mixed. Around 38%—the largest group—indicated that they understood what their child was learning “more” or “significantly more.” However, 32% indicated that they had about the same understanding, and a surprising 30% said that they actually understood less. While the majority of parents are more involved in their child’s education through distance learning, there is clearly room for improvement.

What did parents miss most about the traditional school environment?

When parents were asked the open-ended question, “If applicable, what do you and your child(ren) miss most about a traditional school environment?” almost 63% of parents wrote in a similar response: friends and socialization (see Figure 11). For comparison, the next highest category was “teacher” at 15%.

“She misses the interactions with her teachers and friends,” wrote one parent, summarizing the comments of more than 700 others out of over 1,200 respondents. Most parents just wrote the word “friends,” but some were more elaborate. “Social interaction,” one wrote, ”the ability to explain and work through problems from multiple perspectives. At home, they only have me to bounce ideas off of—no peers or teachers.” About 5% of parents indicated that they and their kids also missed extracurricular activities.

Besides friends, teachers, and extracurriculars, another 5% of parents mentioned missing independent time away from their children. One respondent wrote about missing “everything: an actual education (lessons being taught by an actual teacher), the social component, and time apart from one another.” While time apart seemed critical for maintaining healthy relationships, others again noted the challenge of working with a student underfoot. “My partner and I both work full time,” shared another respondent. “I have been going into the office this whole time, and he has been working from home. It is hard for us to fit the extra time into our days, especially since we both work 50+ hour weeks.”

Though flexibility was noted as a benefit to distance learning, around 5% of parents’ responses indicated that they missed the structure provided by the school day. “I miss him being on a schedule,” wrote one parent. Another 5% indicated that they didn’t miss anything at all, while only 2% indicated that they missed everything about traditional school.

Is all that enough to encourage parents to transfer their students away from their current schools? For nearly a third of parents, the answer is yes (see Figure 12). A little less than 10% of parents expressed a desire to move their children to private school; 8% say they will homeschool; 7% will move their children to online or blended programs; around 6% will move their student to public school; 3% will move their students to a charter school.

Despite lukewarm support for distance learning, parents’ level of trust in their child’s school actually tended to stay consistent, or even improve. When completing the sentence, “Considering how my child(ren)’s school(s) have handled the COVID-19 crisis, I now trust my child(ren)’s school(s)...” most parents—46%—indicated “about the same.” Around 34% of parents had more trust in the district compared to 20% with less trust (see Figure 13). Even if distance learning wasn’t a smashing success, many families were impressed with their district’s response.

What needs to be improved?

While small groups of parents either loved or hated distance learning, the majority took the time to recommend improvements to the system. At the end of the survey, we asked participants to give school leaders advice: “What would you like school administrators to know about your experience with distance learning?” (see Figure 14).

Right in line with the rest of the data, 17% were enthusiastically positive about the program without providing advice; 13% were negative, but also declined to give advice; 8% were neutral; and 22% did not answer. The largest group of participants—43%—suggested improvements for their school’s distance learning program.

Of these recommendations, the most common suggestions were for increased engagement, streamlined programming, and more support for and communication with parents. Of course, around 10% of respondents who suggested an improvement noted that without significant support for working parents, their systems were unsustainable. Around 8% noted that their current system excludes vulnerable students, especially those with IEPs. Parents also addressed more divisive issues: whether they preferred flexibility or a strict schedule, whether student workload was sufficient or overbearing, and whether teachers’ expectations were fair or unfair. Parents had differing opinions, but on the whole, more parents called for a tighter schedule with more high-quality learning than a looser schedule with lower expectations. About 3% of parents called for a blended learning option on their campuses.

Now we’ll dive into some of the most commonly mentioned problems with parents’ suggestions for improvement.

Problem: Student Engagement

The most common suggestion for improvement was better engagement with students. Parents indicated that, generally, there wasn’t enough one-on-one attention paid to their students, instruction wasn’t engaging, and there were few opportunities for collaboration.

“Teachers need to be more involved,” wrote one parent. “There was not enough one-on-one learning. My student only had 25 minutes a day with her teacher,” another responded.

Parents were asked to complete the following sentence with answers ranging from “significantly less” to “significantly more”: “During distance learning, the amount of one-on-one attention my child(ren) received from their teacher(s) was...” (see Figure 16). A majority of respondents—56%—said their children had received less one-on-one attention from teachers than usual. For 27%, individualized attention stayed about the same, while only 18% said their children received more one-on-one attention than normal. Notably, suburban and rural parents indicated less one-on-one engagement for their students than did parents in urban districts.

Parent Solution: Build Relationships

- “My kid would actually listen and do his work when he could see a video of his teacher telling him to, even if it was pre-recorded. Having those videos was a lifesaver.”

- “One-on-one meetings with students weekly were a vital part of my kids’ school week.”

- “Hold teachers accountable for real lessons. Some teachers were excellent with daily online lessons and office hours; others never contacted my student the entire three months and made up a grade; others emailed once a month with no teaching material.”

- “I hope to see an improvement in teacher-to-student and student-to-student interaction. My daughter struggled with the loose teacher supervision and lax goals. It would be great if social clubs and sports can be resumed in some revised manner.”

Problem: Lack of Organization

The next common issue raised by parents was simply a lack of planning—which is clearly an extension of the circumstances. Around 21% of parents wrote in advice for school leaders to streamline their program: implement teacher training, pare down the number of apps and platforms used, and provide tools to create an effective learning environment. “At the beginning, we were using a total of nine different learning websites, which is way too many to keep track of and navigate,” noted one parent.

Across the board, parents called for more streamlined access. We asked, “How many apps do you estimate you use to keep track of your child(ren)’s education (For example: Remind, Moodle, Canvas, ClassDojo, Bloomz, district app, etc.)?” (see Figure 15). Though a little over half of parents used one or two apps, over a third used three or more. “Going to 7-10 different websites, programs, and platforms was overwhelming and time-consuming,” wrote a respondent.

There is also the common question of accessibility. We asked parents their preferred technology: “When accessing information about my child(ren)’s education (grades, homework, communication, etc.), I would prefer to use a…” (see Figure 17). While 10% preferred a tablet, 35% wanted to access information on a smartphone. And though 55% of respondents preferred a laptop or desktop, we noticed something striking. Almost every participant—95% of parents—took our survey on a smartphone. Clearly, parents are reaching for their phones. But when it comes time to look up information about their child’s school work, there’s a barrier—we would guess this is from ease of use.

Later in the survey, we directly asked parents about ease of use. As parents completed the following sentence with the range of responses mentioned above, “Accessing information about my child(ren)’s education (grades, homework, communication, etc.) from a smartphone was…” about 58% indicated that access was “somewhat easy” or “very easy,” which indicates that ease of use might not be as significant of a problem as expected (see Figure 18).

However, disaggregated data shows a complication: both urban and rural parents indicated that they found accessing this information to be more difficult, on average, than did suburban parents. A higher proportion of rural parents—41%—prefer to use a smartphone to access information about their schools (see Figure 17). Income made a difference as well; lower-income families are having a harder time getting information off their phones. Parents making less than $50,000 a year were significantly less likely to mark “very easy” or “somewhat easy.” We know that lower-income families are more likely to depend on a smartphone to access the internet. If apps, programs, and district websites are not easily accessible on mobile devices, the district risks excluding students.

Parent Solution: Streamlined Programming

- “I would like them to rethink the whole school experience to be an optional on-site and mostly remote learning experience, like work. There’s an evident lack of a well thought-out plan of how to improve remote learning. Think outside the box!”

- “With more preparation, it could work well. If all of my kids’ assignments and grades could link up to one site, it would be great! Having one in middle school and one in elementary, they are wildly different. If I could access one place for both kids, it would help tremendously.”

- “Use fewer apps. It is difficult to keep track of everything.”

- “Many faculty are incapable of teaching online. Faculty also need more training about how to use an LMS and how to engage students with distance learning tools.”

Problem: Confusion

In around 12% of open-ended responses, parents called for more support: better communication with their child’s school, training in distance learning plans, and less hands-on work.

We asked parents to evaluate the frequency of communication from three separate groups: their children’s teachers; building-level school leaders like principals or other school administrators; and their district—the superintendent or other district administrators (see Figure 19). Each question prompted participants to indicate a range of responses from “far too frequent” to “not frequent enough.”

Surprisingly, parents indicated similar responses across all three questions: in each question, around 60% marked that communication was the right frequency. Otherwise, responses generally skewed towards “infrequent,” with between 27-30% of respondents indicating that communication was either “very infrequent” or “somewhat infrequent” across each question. Suburban parents were more likely to indicate that communication with their district was not frequent enough or far too infrequent. Still, a little more than an average of 10% of respondents were overwhelmed by communication.

Parent Solution: Communication and Support

- “Although our district has a ‘home portal’ where parents can see their children’s assignments and grades, teachers weren’t keeping them up-to-date, and I couldn’t keep track of my child’s assignments. There were times a teacher would update after weeks of no communication, and I would suddenly realize my student was far behind. It would be so helpful if there were a daily update on student work.”

- “There needs to be more efficient communication. I received so many emails and calls every day, and it was often hard to organize the information. I felt overwhelmed a lot of the time. I think fewer emails, combining information, would be better. Also, I received multiples of the same email day after day. Once a week should be sufficient.”

- “Be mindful that most families have multiple students. So sending emails—especially to parents of high school students—is highly confusing not knowing which of my students the information is directed at. Also, highly overwhelming to get multiple emails per week from more than 20 teachers.”

- “There needs to be more detailed instructions for parents to monitor and understand assignments and due dates.”

- “I think teachers need more training on this style of teaching, and parents need more resources to be able to help our children.”

Problem: Too Much Busy Work

Student workload and learning expectations were divisive issues, highlighting inequities in the system. We asked parents to complete the following question with responses ranging from “far too small” to “far too large”: “During distance learning, my child(ren)’s academic workload (coursework, homework, lessons, etc.) was…” (see Figure 20).

Only 44% of respondents said they thought the academic workload was the right amount, with 33% saying there was too much work and 23% saying there was not enough. However, when we disaggregated the data, we found that the concern about a light student course load goes up by income level. Parents with an annual income of more than $50,000 were more likely to indicate that the course load was “too small” or “far too small.” In short, wealthier parents could afford to have higher expectations for their students’ academic growth during the crisis.

In the open response portion of the survey, 7% of parents indicated that expectations were set too low for their students. “I felt a lot of the distance learning assignments were busy work‚ and kids didn’t take it seriously,” wrote one respondent. Another indicated, “I don’t feel like my child was challenged at all.”

On the other hand, around 5% of parents asked for more flexibility around workload and grading. “Be considerate of the workload given to students that don’t have access to technology,” wrote one parent. “There should be less of a workload,” advised another. While many parents indicated that workload was too high, the work provided was often described as “busy work”—students weren’t supported or engaged in learning. So it seems that teachers’ expectations in terms of quality were indeed too low—even if the workload was too high.

What’s more, what is deemed as the “right” workload seems to be dependent on students’ circumstances at home. While some students weren’t challenged by the work, others struggled to keep up while babysitting siblings or driving to reach a WiFi signal.

Parent Solution: Raise Expectations

- “Some families have more than one child to help. Teachers’ demands and constant emails and calls were cumbersome as we had more than one child distance learning, and I was working 40-45 hours a week as essential personnel.”

- “The workload was far too much, and they didn’t learn as much as they could have.”

- “I would say that kids are not getting anywhere near the same level of education at home that they would at school. Most assignments since March were just practicing what was already learned earlier in the year, and not new material. Most parents are working and may have more than one child at home. Especially with younger children that need guidance, parents I know do not have the time to spend teaching (if working).”

- “Some teachers gave an ample amount of work that wasn’t necessary. However, they did manage to do a good job on upgrading grades constantly.”

Supporting School Leaders

While this survey focuses on ways for school leaders to improve, we wouldn’t be telling the full story without acknowledging the outpouring of support in parents’ open responses. A few parents even gave shoutouts to particular districts, congratulating leaders on a great response. (We’re looking at you, Robertson County School System and Anne Arundel County Public Schools.) In general, words of thanks and encouragement abounded.

- “I would like school administrators to know that we appreciate the effort they’ve put into making this transition as easy as possible.”

- “You guys hit the ground running and did a fantastic job of teaching my children from a distance.”

- “Thank you for rising to the challenge of implementing distance learning curriculum so rapidly.”

- “Thank you for all you did to quickly adapt to the situation and keep the kids on track!”

- “God bless them—I don’t know how they do it.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!