Levy Campaign Deep Dive: Greene County Career Center

Building Trust · Learning Community Needs · Leveraging Community Infrastructure · Encouraging Student Advocacy

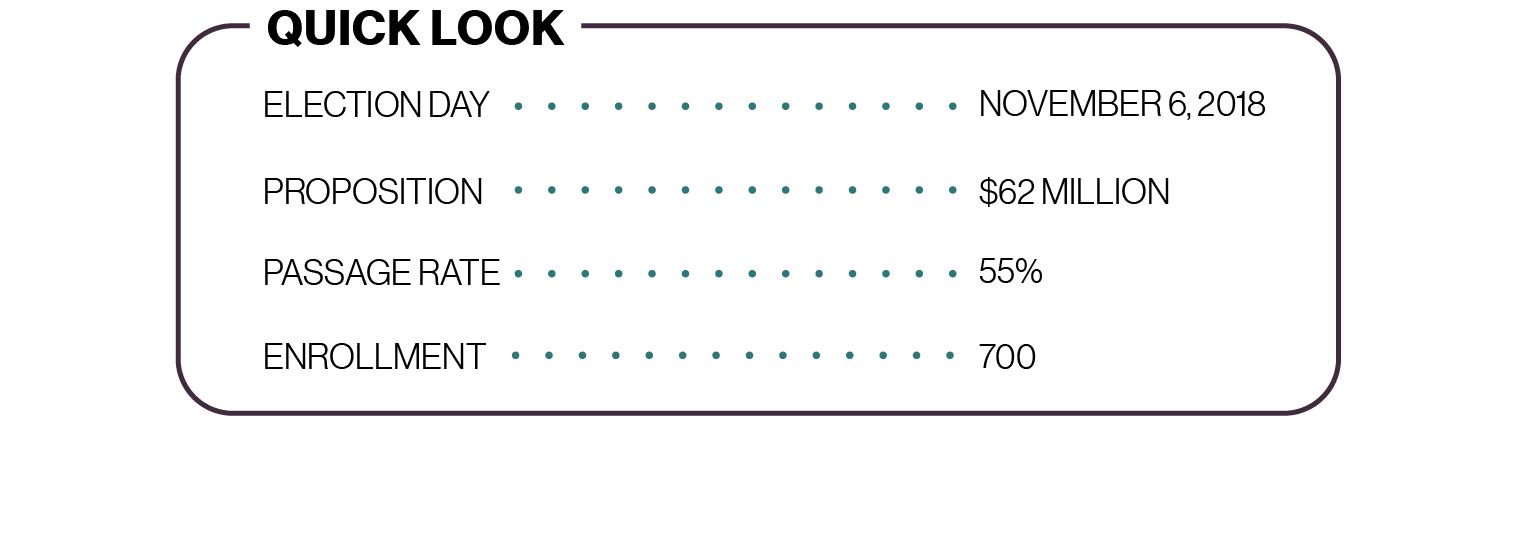

In November of 2018, Ohio’s Greene County Career Center (GCCC) successfully passed an $62 million levy to replace its 51-year-old facility. But passing a levy had never been the center’s Plan A.

“We’d started by trying to seek state funding,” GCCC Superintendent David Deskins tells SchoolCEO. But according to Ohio law, the state’s 49 career centers, including GCCC—can only apply for funding to remodel existing buildings, not to build new ones.

GCCC’s solution to the predicament? Try to change the law.

Working with various state legislators, Deskins and his team presented new legislation that would shift the way the Ohio School Facilities Commission operated. And it worked—the Senate added the language. The new law made it all the way to the desk of then-standing governor John Kasich, who struck the item down last minute. “So we were back to the drawing board,” says Deskins.

Unlike a traditional school district in Ohio, GCCC serves an entire county. “We’re a local shared resource for workforce training for high school students,” Deskins explains. “The kids come to us during their junior and senior years and earn accredited hours, so that when they leave high school, they can enter military service, go on to college, or go directly into the workforce with an industry certification.”

The programming at GCCC provides critical pathways for hundreds of students, putting all the more pressure on the Greene County team to find funding for a new facility—and eventually pushing them to go out for a November levy.

Lessons from Greene County Career Center

- Invest in the community's trust

- Learn from what the community needs from their schools—and their graduates

- Tap into the natural infrastructure of your community

- Teach students to advocate for their own education

Invest in the community's trust.

As it turns out, Deskins’s search for funding wasn’t in vain. By showing the community the center’s needs, he started to build the need for the levy—and showed taxpayers that he was fighting to keep expenses down. Instead of immediately going for the bond after failing to adjust the law, Deskins continued saving for the new building out of GCCC’s budget.

“We had been saving diligently to try to offset the cost for any kind of a levy request,” Deskins explains. GCCC had $18 million—about 23% of the new building’s cost—stashed away. “We felt that was really important to the public,” he says. “They saw that we were being careful stewards and utilizing the funds they had given us, saving toward this and not expecting them to contribute extensively.”

Deskins also wasn’t willing to go out for a bond without confidence that the community would support it. “Ultimately, we wanted to gauge the community before we put this on the ballot,” says Deskins. So GCCC ran a survey, looking for answers to three key questions.

“The first was their level of confidence in us as a career center,” Deskins says. “Were they familiar with who we were? Did they support what we do?” The answer to both was a firm yes. “About 77% of our public firmly believes in the benefits of the career center.”

GCCC also wanted to double-check that the market research they’d conducted in the 2015-2016 school year still rang true in the community. “That research identified our region’s current job needs,” Deskins explains. “So in December 2017, we wanted to know—do these careers make sense to us in Greene County, Ohio, as needed jobs in our region?” Again, a resounding yes. “Over 90% of our registered voters said, Absolutely. We believe those jobs promoting aerospace careers are pivotal to this region.”

“So that’s fine and dandy,” Deskins says. “You can have confidence in the career center. You can believe we need this programming. But when push comes to shove, the real question we’ve got to answer is, Are you willing to help pay for it by way of a tax increase?” When 59% indicated that they’d be willing to fund the cost of the new facility, the deal was sealed. “That gave our board the confidence to go to our public and try to pass a levy.”

Going forward with the campaign, community feedback would continue to shape the levy measure and the messaging that surrounded it. “I think the pitfall is coming up with an idea to build a new school or new stadium and then going to the community asking for buy-in,” says Ron Bolender, GCCC’s Public Information Administrator. “It should be the other way around—the school should already know what the community expects of them.”

Learn what the community needs from their schools—and their graduates.

Deskins and his team anchored their messaging on one central theme. “Our driving factor was the importance of building the workforce,” he tells us. “That was the common theme in everything we did.” The new facility wasn’t the focus—just the means to an ultimate end. “We’ve watched some of our other communities talk about the dire conditions of their buildings, and they fail,” says Bolender. “We determined that we’d talk about the growth and benefit for students, not necessarily the age of a facility.”

“We view this opportunity as a chance to set the stage for the next 75 years of building that workforce,” Deskins says.“If the community tells us that they want us to stay where we are and not allow those opportunities for our students, we will continue to deliver exceptional training—but we’re going to lose businesses in our region because they’re looking for higher-equipped students. We need your help to prepare our kids for those future jobs.”

Though this core theme stayed the same, “there wasn’t a one-size-fits-all message,” Deskins explains. With such a diverse audience, there couldn’t be. “Running a levy across seven towns, you need to count on all of them—but each one of those communities wants a little bit of a different twist.”

To determine which messages would land in which towns, GCCC once again asked their stakeholders. “We utilized leaders from each of those communities to give us insight on what messaging mattered to their towns,” Deskins explains. “Because we knew our audiences in these different communities, we could address what we knew were their concerns.”

And that community knowledge didn’t just come from leaders—it also came from active listening on the campaign trail. “Each time you’re speaking at those engagements, you’re getting pounded with questions,” Deskins says. “If you’re paying attention, questions give you the ability to garner a lot of feedback from your public.”

For instance, constituents in the county’s more rural communities worried that with the advent of new programs like aerospace engineering, agriculture and other skilled trades would fall to the wayside. So they asked about it. “That wasn’t in our survey anywhere,” says Deskins. “But once we were talking about the levy, we started getting a lot of questions about our current programs—Are you keeping things? Are you getting rid of things?”

“So we listened,” he says. “We immediately adjusted our marketing to address what we heard during our presentations, our public engagements, our business advisory meetings. Every time we went out into the public, we viewed it as an opportunity to garner feedback, then modify the message.”

Tap into the natural infrastructure of your community.

GCCC might have been forced to raise their funding through a levy—but the time they spent trying to change funding laws paid off in its own way. “The work that we’d done on trying to pass the legislation allowed us to really get a strong delivery message to different state legislators and politicians—folks that had served in office,” Deskins says.

And those relationships, in turn, led to more relationships.

“Our local business leaders are already connected to those state officials,” says Deskins. “They’re probably contributing to campaign funds for some of those state legislators or leaders, and as a result, they already have an open door policy of connectivity to them. So I utilized relationships with all of those entities to find out: Who are the important people that need to be in the loop on what we’re doing? And how do we best reach them in a way that will garner their awareness and, hopefully, their buy-in?”

The support of local businesses, for a career center, is paramount—even more so than for a traditional school. “So we leveraged business and industry,” says Deskins.“We called on them to get involved.” Through business advisory boards, GCCC has assembled groups of 10-12 business leaders from each offered career path, who give advice and critiques to the center’s instructors. “We rely on them to not only help us spread the information, but to provide the support to parents and students around their industry and what they need,” Deskins says.

Naturally, this community support proved extremely useful during the bond campaign. “For instance, a former governor of Ohio is one of our business advisory members,” Deskins says. “So we utilized him for a quote on our mailers, but his help and support—talking to other business leaders when he was out on the speaking circuit—was also very pivotal for us.”

Teach students to advocate for their own education.

“Our best marketing strategy is letting people come and see what our kids get to do everyday as part of their training,” Deskins says. “We have people from all walks of life coming in to see what we do and offer.”

It’s not unusual for these guests to be pretty high-profile. “Our current seated governor lives in our county—he has been on our campus probably three or four times in my five years here,” says Deskins. “All of our business advisory teams come into our building at least twice a year. We’re constantly giving tours to different government and local community leaders.”

Students, in turn, rise to the occasion. “My kids expect me to come through their lab, probably at least one day a week,” Deskins says. “They all understand that when I walk in, no matter who I’m with, you’re expected to walk up, look them in the eye, shake their hand, and tell them about what you get to do at this career center. It is your job to help them understand why this kind of school matters to you.”

“My students take that seriously,” says Deskins. After all, it’s not just promotion for the school—it’s also career training. “We really spent a lot of time stressing to our staff that customer service was going to be essential for the future of these students. So as the adults, we had to not only model it, but get really good at it.” And when the kids learn by example, and prove what they’ve learned, they’re rewarded. “I try to go back into those labs and commend the students for the impression they made on that adult, which only further creates the desire for them to do it,” he says.

Building a culture of appreciation takes time, especially from Deskins. When asked how he took care of himself during the levy process, he just laughs. “If you talk to my wife, she would tell you that I didn’t,” he says. “My schedule and my pace was way more than she thought I should have been doing.” On a typical week, Deskins works 9 -12 hours Monday through Saturday—and sometimes Sunday as duty requires. During the levy, he was working up to 16 hours a day, seven days a week.

But all that work was well worth it. The levy passed, with 55% of the vote, and GCCC has already broken ground on its new facility. You can find up-to-the-minute updates through a construction live feed on the school’s website.

“The volume of work in a new building project has been nothing less than utterly exhausting,” Deskins tells us. “But I get to see the dream of the future for tens of thousands of students in this county, giving them opportunities they would never have been able to attain had we not chosen to go forward. It’s a really challenging role—so I feel really blessed to have been asked to come and do it here.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!