The Five Stage Bond Campaign

Lessons from over 50 districts on the path to bond success

Starting the process of a bond proposal may feel a little like standing at the foot of Mount Everest. Looking up toward your towering final destination, you can’t fathom how you’ll ever reach it. Whether it’s climbing the world’s tallest mountain or proposing a multimillion-dollar bond, monumental tasks are often smaller tasks strung together. A mountaineer has daily distance goals, places to stop and camp along the journey. As Desmond Tutu once said, “There is only one way to eat an elephant: a bite at a time.”

What follows isn’t a how-to guide, because as we’ve already discussed, one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to bond campaigns. Instead, it’s more like a climbing route, guiding your trek up the mountain. This framework breaks down the overwhelming process of a bond into smaller, more manageable stages. Each stage serves a different purpose and works toward a different goal, but these goals build on one another to produce a successful overall campaign.

Drawing from our conversations with leading school administrators from over fifty districts across the country, we’ll break down the five stages common to most successful campaigns.

This article explores the work of both districts and auxiliary advocacy committees. We encourage school district officials to thoroughly research state requirements and restrictions for the campaign. SchoolCEO ensured that each of the districts and individuals mentioned in the article remained in compliance with state laws pertaining to bond communications.

Stage One: Building the Proposal

Goal: Develop passionate campaign advocates.

Stage One includes the process of building the proposal: everything from a facilities study to town halls to formal community surveys. Of course, this process changes from one community to the next depending on the size and capacity of the district. However, almost every superintendent we spoke with agreed that it’s crucial to take this process outside the walls of the district office, putting decision-making power in the community’s hands.

The more we invest in a project, the more we’ll get out of it. This is more than just an old maxim. It’s proven by social psychology—the formal term is “effort justification.” We believe that our effort has purpose, and if the purpose isn’t clear, we’ll create it for ourselves.

So it’s not hard to see why it’s crucial to involve your community in building your proposal from the very beginning. Each time a district asks for a citizen’s input or invites them to work through issues on the bond, that individual pours a little bit more into the proposal—taking a little more ownership over the project’s success. So through this fact-finding process, the district has an opportunity to grow their own advocates for a bond campaign.

If you need a little refresher on advocates and how to grow them, check out:

schoolceo.com/advocates

What is a campaign advocate, and why do you need them?

During the campaign, you’ll deal with a few different groups of people. First, there are neutrals: citizens who may or may not support the bond—and may not even show up to the polls. Then, you have your adamant No voters. This group is actively against your bond, sometimes even working together to dismantle the campaign. Finally, you have your bond supporters. These voters will likely vote Yes, but only a few of your supporters will turn into campaign advocates.

Campaign advocates are people who not only vote Yes themselves, but also convince others to do so. What we know from looking at dozens of referendum elections is that the most powerful campaigns are run by community members—campaign advocates—not school districts. While billboards and mailers can be effective campaign tools, think about impact. What would sway you more as a voter: a billboard, or several friends proudly sporting campaign stickers? It isn’t always campaign materials that swing the vote; rather, it’s the people who stake yard signs and share photos of their “I Voted Yes” stickers on social media.

“The overall principle is: people influence people,” says Denise Lindberg, Public Information and Volunteer Program Coordinator at Hamilton School District in Wisconsin. The district passed a $58.9 million referendum in 2018. “If you have activated people to spread your message and to advocate for you, that’s the way to be successful.”

How do you get campaign advocates?

This early in the process, you might have advocates for your district, but you probably don’t have many for your bond proposal. So during the planning process, think of every engagement—every phone call or invitation to join the planning committee—as an opportunity to plant the seed for a potential campaign advocate. To really reach into every corner of the community, you’ll need to invite a diverse group of stakeholders.

At this point in the campaign, allegiance to the district isn’t important. In fact, several school leaders advise districts to invite individuals they assume to be No voters into the planning process. This diversity of feedback results in a proposal that the entire community feels comfortable supporting.

Even if these No voters don’t go on to support the bond, they still gain an understanding of the district’s needs. As community members parse through stories of leaky roofs and research on safe schools, they begin to understand the district’s why. And as they do, the locus of power moves from district leadership to the community, inviting them to take responsibility for students’ needs.

Director of Communications Merry Glenne Piccolino from South Carolina’s Aiken County Public School District calls this ripening the issue. “I don’t think it would have been successful,” Piccolino tells SchoolCEO, “if we hadn’t brought our community along on investigating the issues.” To better spread information about a bond throughout the community, it’s important to plant these seeds of advocacy all around the district.

The process is the product.

It would be easy for administrators themselves to choose which projects end up on the proposal. After all, maintaining control keeps the proposal neat and the process efficient.

However, taking the proposal out of the hands of the community at any point in the process leaves space for cracks to form in the structure of the bond—ones that may cripple the proposal. Giving decision-making power back to the public results in a proposal that truly is community-driven, that voters feel comfortable supporting.

As Dr. Gustavo Balderas, Oregon’s 2020 Superintendent of the Year, explains, “The process is the product.” His team’s engagement and refinement work at Eugene Public Schools was extensive, with more than a dozen town halls, a formal community survey, and individual meetings with each building’s staff. Once they landed on a proposal, they’d take it back to the community and board—then refine—then take it back out. This process lasted months.

“What we did right,” says Balderas after the election, “was involving the board and the community right from the onset of everything we were doing. It is exhausting, but it’s the right work because of the benefit to kids.”

Though the editing process takes time, this community engagement can serve as marketing in and of itself. Contributors aren’t evaluating the proposal anymore—they’re fighting to implement their own ideas. And while individual community members shape the bond, the community at large watches as the district adjusts to their input. When the proposal has been approved, you can move on to Stage Two.

Campaigns in Action

Corunna Public Schools: Needs, Not Wants

At Corunna Public Schools, Superintendent John Fattal was part of a process where the community led the revision process from the get-go. “We had maybe 35 groups in our cafeteria, five to seven people in a group,” he explains. Leadership would introduce a topic from their bond wish list, like new turf for the football field, and have groups rate each item’s importance from 0-4. “That helped prioritize what we were going to do with the bond,” he says.

Fattal himself was in favor of installing new turf, which would have potentially saved the district money over the long term. “There were a lot of people who wanted that,” he explains, “but the group consensus was, That’s more of a want, not a need.”

By prioritizing community needs, the process produced budding advocates for the district’s referendum. “Again, I can’t overstate how important it was to get the support of the community to sell it,” Fattal says. When it came to communicating the need for the bond, “the big piece was that core group.”

Stage Two: Developing Your Messaging

Goal: Share your proposal as a story.

Once you’ve decided on the components of your bond proposal, messaging is the next peak to conquer. At first, the prospect of building influential and strategic messaging might seem just as intimidating as starting the climb. But remember, you’ve already made it partway up the mountain.

Think back to the last time you applied for new jobs. You probably had a resume and cover letter ready, highlighting your skills and experience—but for each unique application you submitted, you slightly changed the way you presented yourself.

You didn’t make anything up (at least, we hope not), but you likely didn’t present every detail of your job history with equal weight. Instead, you tailored your application to the specific job you were applying for, emphasizing your most relevant skills and experience.

The same principle applies to building out your bond messaging. It’s not about running a “sneaky campaign” that hides information from voters. It’s about knowing your audience, both as a cohesive community and as segmented groups, and learning to communicate in a way that tells the story of your proposal.

As you start to build unified messaging, you’ll want to develop your slogan—a message your supporters can rally behind. In just a sentence or even a phrase, your campaign slogan is a simple explanation of the proposal’s why. This messaging should help unify every piece of your campaign, from hashtags to PowerPoints.

Beyond your slogan, you’ll need two other tools: audience-specific messaging and basic bond education. Using these tools, you’ll communicate the content of your proposal in a way that’s accessible to each audience.

Campaign Slogan

Your campaign slogan is a concentrated explanation of the district’s purpose, meant to loop in every potential voter. In short, it’s a visioning statement.

From the district’s perspective, creating a slogan is an opportunity to tie the district’s vision or mission statement into the proposal. For Round Rock ISD, a district with a history of academic success, the message was “Building on Excellence.” With a single phrase, the district’s communications team reminds voters of the district’s past success in order to propel the district into the future—all, of course, without advocating for a Yes vote.

Once a district has built out a slogan, the campaign committee has an opportunity to build off of the district’s messaging. The repetition amplifies the message, linking the district’s Facebook post to the campaign committees’ yard signs.

Campaigns in Action

Warrensville Heights City School District: #BuildingOurFuture

The year before Warrensville Heights City School District, located in an “inner-ring suburb” of Cleveland, went out for a bond, the district was in danger of a state takeover. To make the bond process even more challenging, the state’s debt limits mandated that a bond couldn’t be run in Warrensville without state approval.

Unlike Warrensville’s previous superintendents, however, Donald J. Jolly II is a graduate of WHCSD and carries with him a contagious faith in the district. He decided to prove the district could deliver on their promises.

“What we did was make a promise to the community. We’d build our first building without a bond,” Jolly tells us. And they kept their promise. Warrensville Heights secured funding for their new elementary school, which cost about $30 million, without going to taxpayers for help. The move was a huge step towards building community trust.

The district also made sure to communicate the positive changes taking place at WHCSD—like reopening a closed school, boosting enrollment by almost 300 students, and improving the district’s report card rating. “We made some very tangible accomplishments during a short amount of time that people were able to actually visualize,” Jolly explains. “It helped us put that picture of the future into people’s hands.”

So by the time WHCSD finalized their referendum proposal, the community had already witnessed broad, positive changes in the district. This build in momentum grabbed citizens’ attention, ripening the environment for a bond campaign.

When it came time for the Warrensville team to brainstorm campaign messaging, they honed in on this growth, landing on the slogan “Building Our Future.” This future-focused messaging pulled attention away from the state takeover and toward Warrensville’s growth. For parents, messaging on the future coupled with tangible change was a slam dunk, communicating that the district was on a positive trajectory. “We are growing,” Warrensville’s Communications Director Kayla Pallas tells SchoolCEO. “We are trying to build facilities that meet 21st-century needs, and Warrensville is a place they need to stay.”

This future-focused messaging also looped in another group: adults without students in the district. “We had a groundswell of our seniors who are supportive of this measure with the increased cost of their property taxes,” Jolly tells us. About 80% of homeowners in the area are senior citizens, which surprisingly proved to be a huge asset for the district.

“It’s kind of a unique situation,” Jolly explains. “Our most invested seniors truly want to leave the community better. When they came here, all this stuff was new. Now, it has done over 40 to 50 years of service, so they’ve invested in leaving new facilities for the future.”

Seniors didn’t just support the bond—many became some of the district’s most valuable advocates. “We have very key senior citizens who endorsed the measure, and who were part of our marketing out in the community,” Jolly explains. “They understood the value of having new schools, and they put a very strong mandate on me, as superintendent, to continue to improve our schools.”

United, volunteers latched onto Jolly’s positive vision throughout the campaign. “We really focused on the benefits,” Pallas tells us. “Not only to our residents, but also to the students. We are thinking future forward with our district—building something that will leave a positive legacy for decades to come.”

The district’s focus on the future worked—and quite effectively. Their bond passed in November 2018 with 76.9% of the vote.

Campaigns in Action

Wickenburg Unified School District: Splitting the Message

In Arizona’s Wickenburg Unified School District, Superintendent Howard Carlson’s team made the strategic decision to adjust messaging—not what was in the bond, but what was prioritized—by splitting voters into groups. “We had a retiree message, a family message, and a community message,” he tells us. His team even differentiated these categories by geography.

For retirees in the northern part of the district, who have lower expendable income, the fact that the bond wouldn’t raise taxes was a huge sell—so Carlson’s team drove the tax piece home in that area. In the more affluent southern part of the district, the team created “more of a balanced message,” emphasizing that citizens could do something good for their community by supporting the bond. By focusing on each segment’s situation and needs, Carlson could better gain the support of each group.

Audience-Specific Messaging

The point of audience-specific messaging is to highlight different parts of the bond that will appeal to specific voting groups. You aren’t changing the proposal; rather, you’re making the proposal relevant to each voter.

Generally, the two groups most likely to show up at the polls are your supporters and the district’s frequent voters. From there, you can split this core target audience into smaller segments like parents, retirees, small business owners, etc.

As you split voters into segments, ask yourself: What does this group need from the proposal? How will the bond meet that need? The juncture of these two questions is your audience-specific messaging.

Bond Basics

Your audience-specific messaging should tell the story of your bond—strategically prioritizing different aspects of the proposal to appeal to various community members. Part of the district’s job, though, is to educate the community on the entirety of the bond—even the nitty gritty details of your proposal. After all, anything left a little fuzzy or unclear opens the door for naysayers to jump in and spread misinformation.

The last tool in your toolbox, then, is messaging that educates the community on the bond in its entirety. In this part of your messaging, it’s important to be systematic in sharing each piece of the proposal in a way that supports the rest of your communications.

Define your bond in simple terms.

Before you had firsthand experience running or training for a school referendum election, you may not have known what a bond was. Bonds and levies can be puzzling, and they aren’t part of most community members’ day-to-day lives.

So extend a helping hand to voters. Explain why the district needs to go out for a bond in the first place, breaking down tough subjects like the tax impact and broader information about the projects on the ballot. In Texas’s Spring ISD, the district’s communications team created a video explaining the need for a bond using a student’s voiceover. “I’m not sure if you know this,” says the student, “but school districts across the state only receive funding for daily operations. That means that things like new schools, buses, and renovations require funds from a bond.” The video is supplemented with pictures, and the script avoids too many large or technical words.

Organize projects by community.

You’ll need a space to put the longform proposal somewhere in your communications. So as you organize this bulk of information, keep in mind that the closer the benefits feel to each individual voter, the more likely it is that citizens will vote in your favor. As you build out the details of the proposal on your website, break down the bond’s benefits by community: How will each campus benefit from the bond? How will the bond affect senior citizens or businesses?

A bonus tip from Round Rock ISD: Don’t forget feeder schools. Even if an elementary school isn’t receiving any benefits from the bond package, they’ll eventually benefit from projects affecting middle and high school campuses as students move through the school system.

Get ahead of naysayers.

During the campaign, naysayers use a few common arguments to cripple the bond: mistrust in district administration, alleged misallocation of funds on frivolous projects, and resistance to tax increases. To get ahead of the naysayers, we recommend that you prepare answers to the following questions, and any others raised during the planning process, before the campaign.

Can I trust the district financially?

Chances are, tax-averse community members will be some of the bond’s strongest opponents. Before they have a chance to spread negativity about the district’s finances, pump stories into the community about the success of a past bond, a project the district funded without a proposal, or how long the district has gone without asking taxpayers for financial assistance.

How was each project chosen?

Of course, some voters won’t know about the district’s extensive engagement process—so show them how the community helped form the proposal. Post an article describing a student’s idea that made it through to the final design, or share photos of community members looking through blueprints.

What will the tax impact be?

One of the biggest barriers to a Yes vote can be the tax impact on individual households. So address the financials: How long will taxes be raised? What is the individual tax impact? A few districts even shared tax calculators on their websites.

Stage Three: Preparing Your Campaign Advocates

Goal: Train your current campaign advocates to go out and grow more.

Once the district lands on unified messaging, there are steps you can take to keep advocates at the forefront of your campaign. Generally, this involves a formal “volunteer committee” or “advocacy committee” that breaks off from the district to advocate for the Yes vote.

At this point, your advocates are budding seedlings. Fragile and young, they aren’t yet ready to stand on their own. So the preparation stage involves nurturing your fledgling campaign supporters with the training and tools they need to advocate properly for your bond—and to build more advocates. So to ensure that your advocates are spreading consistent information, you’ll want to train them on the right messaging.

The first step, though, is to cement your supporters into advocates. Sometimes, all you need to do is ask—and provide the support and tools for potential advocates to follow through.

Small Group Meetings

The best thing about advocates and key communicators is that one strong advocate can produce several more. To build more supporters, school leaders we spoke with met in person with community members all around the district.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a group of five or if it’s 50,” explains Dr. Paul Mielke, superintendent at Hamilton School District. “If you get a chance to tell your story, it can make a difference, because those five people could be really influential and sway the opinion of 100 people.”

To leverage this idea, many school leaders benefited from “coffee talks” where active advocates host bond meetings in their homes with anywhere from 10 to 30 others in attendance. The talks feel intimate, making the need more personal. Given time, these person-to-person connections develop and expand, growing more and more budding supporters of the bond.

“It’s not the information that influences people to vote,” explains Mielke. “It’s relationships that influence people’s opinions and their actions.”

Teacher Cheat Sheets

Sometimes bond supporters—maybe even your own staff—want to help spread your messaging, but they aren’t quite sure how to do so. To help supporters spread the word, several districts created tools to guide advocates in sharing campaign messaging. This tactic not only prepares your advocates for action, but also gives your messaging great consistency, leading to more unified campaigns.

Many leaders we spoke with were smart about engaging those closest to the district first. At Fond du Lac School District in Wisconsin, Superintendent Dr. James Sebert pulled his staff together for a presentation, inviting questions and comments. “I think the best thing that we did was meet with the staff early and often and get our 800-plus employees feeling excited and good about it,” he tells us.

Engaging staff was the first step, but Sebert sealed the deal by creating tools that helped staff deliver a consistent message. After the initial meeting, Sebert used an online platform to assemble his team’s questions and suggestions. After days of back-and-forth, he put together a “teacher cheat sheet” for staff to reference in the grocery store, in the church foyer, or over the fence. “We really wanted our staff to have the resources and knowledge they needed to help people,” he says. “And it was the key to getting us to have a very successful 60% vote.”

Palm Cards

Districts across the country echoed the idea that providing tools and messaging training was key in passing their bonds. In Ohio, the Worthington City Schools team created miniature messaging cards. “We printed our messaging on what we call palm cards,” says Director of Communications Vicki Gnezda. “Everybody had that messaging, then we also did some verbal training with leaders so that they understood how to reframe things through the message.”

The team didn’t just provide a one-time training, but continued to develop both their messaging and their advocates throughout the campaign. “We had a really good team of volunteers representing all areas of our school district, and we, as the district, met with them weekly,” says Superintendent Trent Bowers. “They are key communicators for us—they’re really trusted.”

Stage Four: Executing the Campaign

Goal: Capitalize on advocates’ sway to gear up for the vote.

By Stage Four, the summit is in sight, but the path is set to get even steeper in the last stretch. Now, it’s finally time to execute the formal communications piece of the campaign: the door knocking, posting, emailing, rallying, calling, and mailing—anything that gets your campaign messaging into the hands of voters.

Luckily, by this time in the campaign, you have the support and resources of your advocates—and likely a separate, volunteer advocacy committee—to help traverse the final distance. While the district needs to stick to the facts, this advocacy committee can more explicitly ask for Yes votes.

But let’s take a minute to think about your position in the campaign. As you’ve parsed through facilities information, met with architects, and dug into the details of school finance, you’ve gradually become more and more comfortable with the bond, its projects, and the district’s pressing needs.

However, to a voter who has never seen a bond proposal, trying to sift through these ideas is, again, sort of like standing at the bottom of Everest. And the average voter might not have a strong enough reason to brave the obstacles.

Think of your marketing, then, as providing every possible way to introduce your voters to the best parts of your bond—extending a rope down to each voter. Instead of introducing all the details of the bond right away, you want to gradually acclimate them to the environment.

Systematic Communications

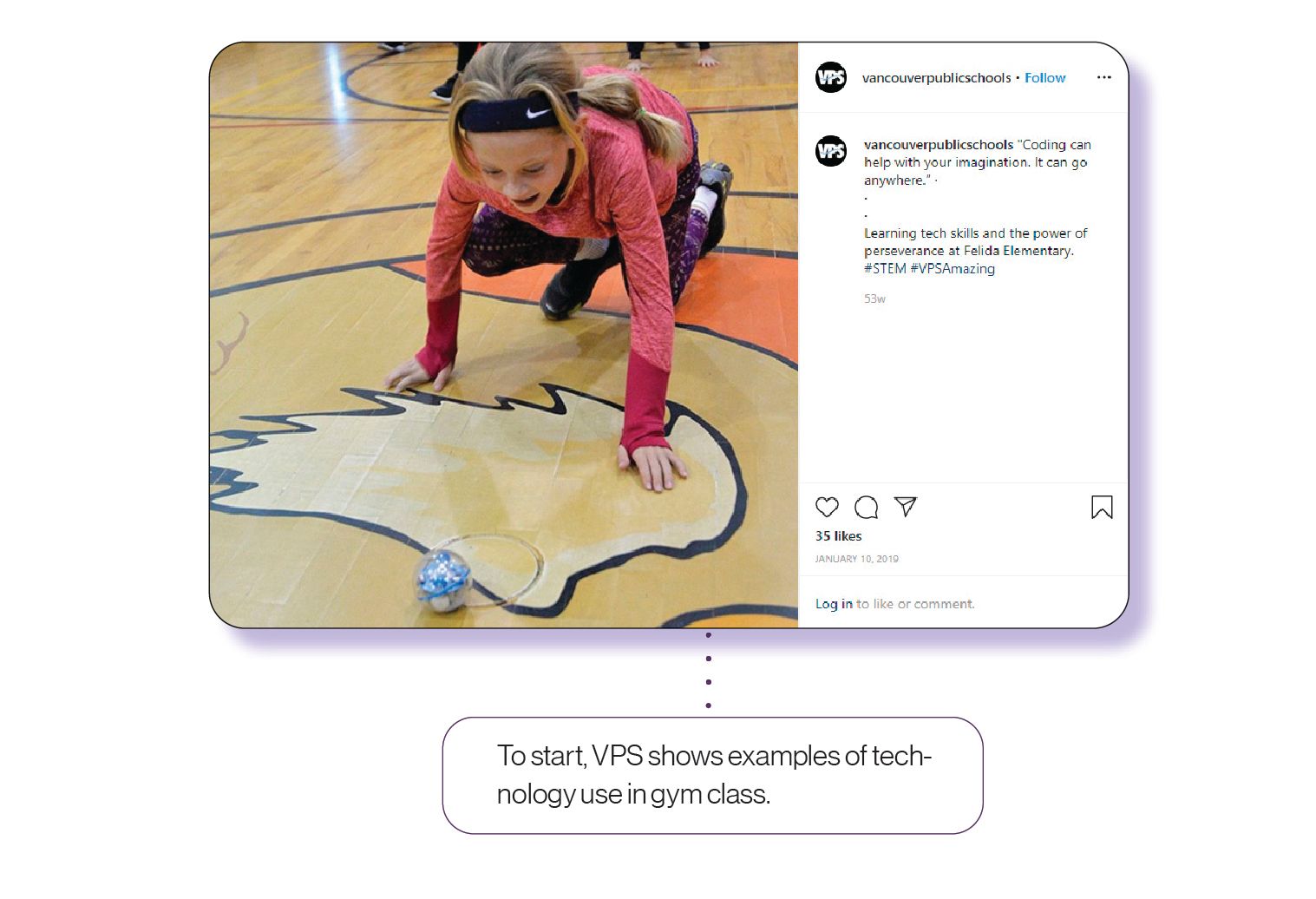

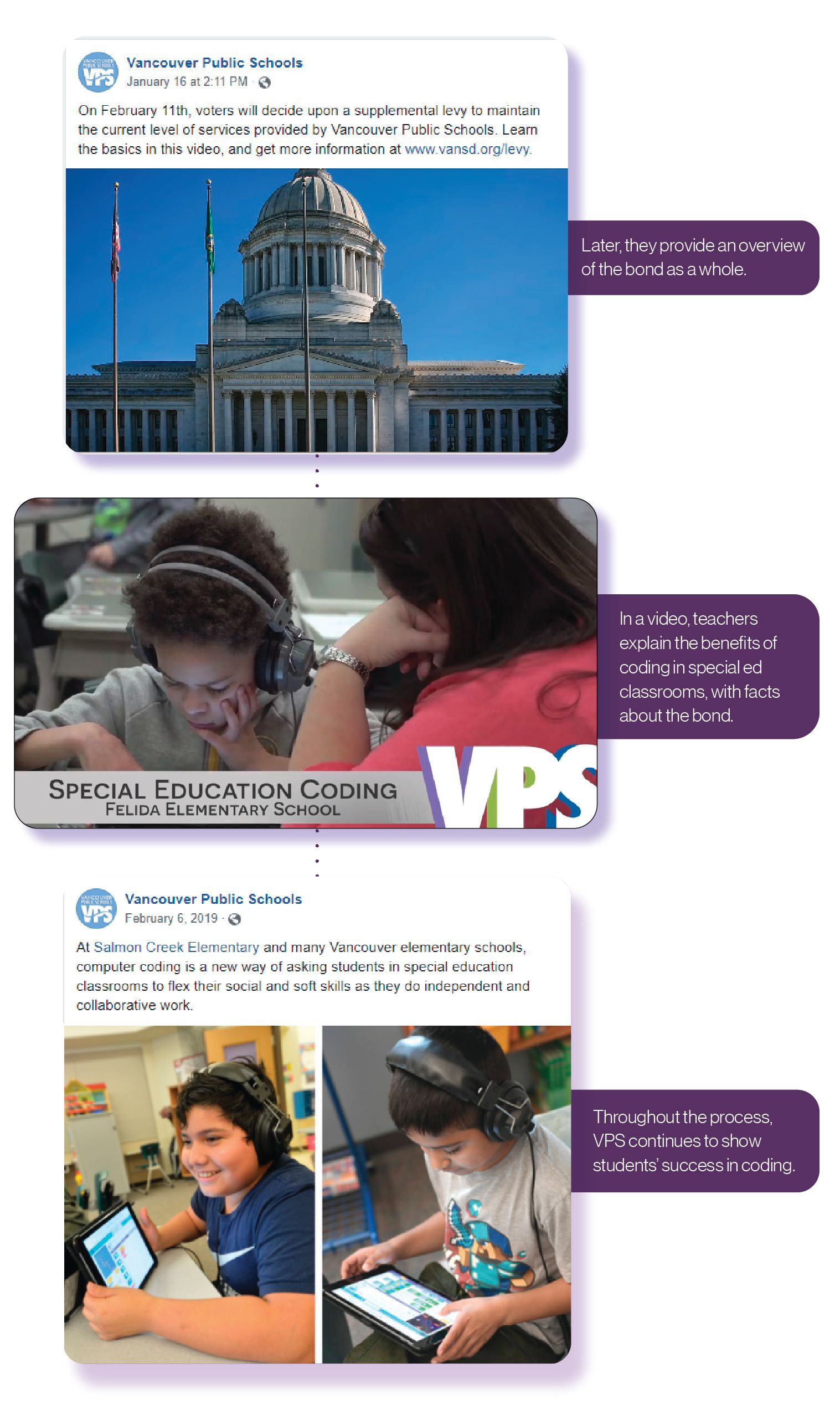

In recent years, private sector marketers have become highly systematic in their communications. Each Facebook post, tweet, email, and flyer is one piece of a greater puzzle, adding substance and clarity to the overall picture of the marketing campaign.

Your bond campaign should operate the same way. To ease your audience into the ideas of your bond, you’ll begin slowly and systematically sharing the details of your proposal, building up to a main ask: a Yes vote. In essence, you want to guide your audience through the thought process that led you to put these projects on the ballot in the first place.

For example, let’s say your proposal includes a new football field. To explain your need for the stadium, you might share images of the football team practicing in ill-suited spaces with text that describes the team’s successful track record. Let your community get to know the team—send a story to the local media about a student whose life has been changed by the sport, and if you can, include information about the bond.

After building the case for the need across several communications channels, you’ll provide your solution. You might share a photo of community members giving feedback on the bond issue, then, a simple description of the tax impact. Don’t focus on one project for an extended period of time; rotate these posts and use different channels to stay top of mind without overwhelming your voters. Then, just before the vote, you’ll ramp up your communications, almost inundating the community with your story.

You’ll repeat this guiding process with all your bond projects, answering the burning questions your audience is probably asking: Why is this project on the ballot? Who will it benefit? Why does the district deserve it? By showing need, highlighting the benefits to students, and exemplifying the district’s trustworthiness, you can systematically bring your audience around to your side.

And while it seems like the traditional “marketing” piece is just now coming into play, you’ve already created your strongest marketers: passionate advocates for the bond.

Using Advocates to Personalize

Most of the time, traditional campaign tactics like door knocking and phone banking have advocates built into the equation. In each case, there’s an advocate asking each voter to consider passing the referendum. In an advocacy-based campaign, this idea should structure most of the district’s communications.

Remember: people influence people. Your audience is more likely to listen to average community members than to you. So as you move forward, consider how you can highlight your advocates’ voices—not your district’s—on as many communication channels as possible.

While taking the time to build in connections often takes more work, the payoff is generally greater in the long run. To get started, work through these questions:

Where is your audience getting information? To answer this question, a few districts conducted surveys or even checked in with their advocacy teams. Think broadly: the newspaper, social media, community events, even faith communities. The goal is to narrow down the communications channels where your messaging is most likely to get into the hands of voters.

How can you plug your advocates into these channels? If you realize that most of your audience is on Facebook, then encourage advocates to share bond posts. Whether you’re sharing information on social media, in the newspaper, or through face-to-face engagement, each channel will be much more effective if your advocates act as spokespeople.

Campaigns in Action

Corunna Public Schools: Handwritten Letters

In Corunna Public Schools, Superintendent John Fattal’s team went through a voting list from the previous election and then narrowed down, name by name, the people they thought might be Yes voters. Then the team did something exceptional.

“We wrote a personal, handwritten letter for each person who we thought supported us in the last election, reminding them to vote,” says Fattal. “We had a lot of people tell us afterward that that was a really important piece for them.” Fattal’s team focused their effort on potential Yes voters, leveraging the influence of their advocates.

Campaigns in Action

Heber Elementary School District: Getting Shares

Heber Elementary, a relatively small, “familial” district in California, knew that in order to catch older voters’ attention, they’d need to capitalize on the social media reach of their advocates. So to encourage likes and shares, the advocacy team asked parents to volunteer students to appear in a marketing video for the bond. “Parents love to share pictures of their children,” says Superintendent Juan Cruz—and he’s right. The starring students’ parents became natural marketers, sharing the video and driving views.

Campaigns in Action

Northwest Allen County Schools: Leveraging Media

At Northwest Allen County Schools, Chief Communications Officer Lizette Downey works to build relationships with the local media early in the campaign. “I do a lot of direct pitching to the media,” she tells us. “I would highly advise other school leaders to contact their print media editorial boards and have your superintendent and communications person sit down and meet them.” Even though the resulting coverage isn’t always positive, the connection often pays valuable dividends.

In that initial meeting, Downey explains any needs and obstacles the district is facing in detail. “That will serve you well, because if they have questions, they will pick up the phone and call that superintendent,” she explains. “That happened a lot for us, and it’s very useful.”

“I would also encourage school leaders to plan out—just based on the size of the community—some media hits of different upcoming events,” says Downey. Instead of merely announcing the annual school play, Downey looks for a personalized story. “If you can pull out a kid who has found an interest in theatre that motivated them to stay in school, I try to get those kinds of stories into the hands of the feature writers.”

During the campaign, Downey leveraged these contacts as well. “We also recruited our political action committee parents to write letters to the editor, and we had those strategically timed,” she explains. Anyone who volunteered to write a letter got some help from Downey’s team: messaging guidance, ideas, samples, and information on where to send it. “You want to make it as easy as you can for them to follow through,” she says.

Adjusting the Campaign

During the campaign, misinformation is inevitable. Someone mishears the facts, or tax-averse community members organize a formal faction to unravel the district’s work. These groups are nothing to brush aside; left unchecked, they’ll cost the district valuable time and energy, spreading seeds of mistrust throughout the community.

Still, opposition is natural, even expected. While you can take steps to avoid controversy, the campaign’s strength lies in the team’s ability to pivot.

At this stage, advocates become more important than ever, slipping into conversations that school administrators can’t access. With their wide reach, advocates can alert the district about any confusion or opposition growing in the community. Using this information, the district can adjust their communications to get ahead of the opposition. Plus, if advocates are armed with the facts, they can challenge misinformation as it occurs.

Campaigns in Action

Hamilton School District: Starting Early

Superintendent Dr. Paul Mielke started planning for misinformation far before the campaign began, asking his initial planning team to write down questions they’d heard in the community about the bond. Then, he turned these questions into an FAQ sheet. “We had a pretty extensive list, probably 30 to 40 questions, and all the facts,” he says. Parents used these FAQs to inform themselves and others. “They were talking to their neighbors either on social media or face-to-face, making sure that they had accurate information,” he tells us.

Then, when advocates heard misinformation, they let Mielke know. And Mielke didn’t wait for that negativity to fester. “I did a number of individual phone calls,” he tells SchoolCEO. “If they found out that a neighbor was being very negative or had misinformation, I called to clear anything up. I don’t know if they voted Yes, but at least they understood the rationale for what we were doing, and why we were doing it.”

When other school leaders asked why Mielke would waste time on a single voter, he explained the power of reach. One person who is adamantly against a bond reaches many others, so quelling their distrust not only stops their negative influence, but might even grow an advocate as a result.

“If you can switch over one person who is very adamant against the bond, then neighbors start asking: What happened?” he explains. “And they become an advocate for you.”

Campaigns in Action

Aiken County Public Schools: Targeting Opposition

During Aiken County’s 2018 campaign, the district faced organized opposition. “I really went after negative criticism,” Merry Glenne Piccolino tells us. “We had such a short window of time. Negative information and misinformation can spread so quickly.”

So Piccolino took action. She first used her advocates to learn what the opposition was up to. “It wasn’t uncommon for someone to drop by my office with a flyer that had been left on their doorstep,” she says. “I wanted to be aware of what they were communicating and review it to determine if it was factual or not. If it was causing any level of concern, what they communicated clearly needed some explanation.”

To start, Piccolino and her team tried to address the misinformation personally. “I listened to what they had to say, and we tried to meet with them to understand their points,” she says. The opposition, however, refused to meet with the district. So Piccolino tried to learn where they were coming from in order to adjust her messaging. “On a very basic level, I studied their communications and determined where they were getting their numbers from, which fueled my communications,” she says. “I was able to explain it, debunk what they were saying, or provide some clarity.“

Then, she made this information public. “We devoted an entire section of our website to correcting misinformation about the bond campaign,” she explains. “Then I created some social media ads to correct misinformation and lead people back to our website for the truth.”

While addressing the misinformation, Piccolino kept it kind and factual. “I did it in such a way that was respectful, just like I did with any other communication,” she says.

Sealing the Deal

Now, you’re almost cresting the mountain. But instead of resting on your laurels, it’s time to invest all your resources, energy, and momentum into the vote. Treat this final stretch as a celebration and an opportunity. Election Day is when you can finally translate the positive momentum of your campaign into action.

And of course, you’ll need your advocates to keep pushing voters up the mountain. So invite advocates to post a quick photo of their voting sticker with a caption describing their reasoning and enthusiasm. Share these posts from voters. Line the streets near your voting location with staff and supporters. In these final stages, we recommend districts leverage all their advocates one last time to drive their peers to the polls.

“At the end of the day, if you’ve got that face-to-face engagement,” says Superintendent Tim Throne at Oxford Community Schools in Michigan, “that can be the difference between: I am going to take action, or Well, I may agree, but I’m not motivated to go and act.”

Campaigns in Action

North Branch Area Public Schools: Getting Out the Vote

Even though it’s been nearly three years since Minnesota’s North Branch Area Public Schools held their 2017 bond election, Superintendent Dr. Deb Henton still has the voting results saved to her desktop. “And I pride myself on having a clean desktop,” she says. “It is one of the greatest pictures that I will ever have in my lifetime.”

To Henton, passing this bond held special significance: the district had failed to pass their last seven attempted referendums, going 15 years without a successful bond. Ever resilient, Henton and her team started planning for their 2017 campaign the day after the 2016 vote fell short. She enlisted the help of Dr. Don Lifto, an expert in school bond elections, to conduct surveys with his municipal advisory firm Baker Tilly. After conducting in-depth surveys with the firm, Henton’s team gained a little insight into what went wrong. In short: “Our parents did not vote in great numbers at all,” Henton explains.

For their next election, North Branch set out to attract parents to the polls, offering opportunities to vote long before Election Day. “One of the key factors in our victory was early voting,” Henton says. Any registered voter could swing by the school to vote during business hours. “Our school board even set longer hours on specific days,” she explains. “We were really strategic about when we had the district office open for early voting.”

The team got creative in how they encouraged voters to show up, too. “We had a petting zoo for our families,” says Henton. “And if they had an I Voted sticker on, they got a free Dairy Queen ice cream.” Of course, Henton checked beforehand to make sure that the zoo was an appropriate distance away from the polling zone. “Then, the night of our elementary carnival, we had a special table letting people know they could go vote early—and we had early voting open,” she says.

School building staff also played a key role. “Our early childhood coordinator would let families know when they dropped off kids that they had this opportunity to go vote,” Henton explains. “She’d offer to watch their kids if they wanted to go vote early.”

Fortunately, this work paid off. Early voters turned out in droves. “In 2016, we had less than 200 early voters,” says Henton. “In 2017, we had close to 800 people.” As it turns out, those early votes would make a huge difference. “The second question actually failed the day of the vote. But when you added in all the early votes, it passed,” she says.

“I would say to people that are trying,” Henton tells us, “that if you are able to be successful, it will pay you back so many times. Your efforts will not have gone without notice or in vain, and it’ll be such a wonderful thing.”

Stage Five: Moving Forward

Goal: Lay the groundwork for the next campaign by maintaining trust.

We caught Superintendent Dr. Tammy Campbell on the phone right after her district, Federal Way Public Schools in Washington, successfully won their second of two groundbreaking referendum elections. “What we’re doing right now,” Campbell explains carefully, “is laying the foundation. Our next bond will be passed based on the way the community feels informed.”

At first glance, it might seem like a bond election is a contained event: beginning with the proposal and ending on Election Day. But what Campbell illustrates is that a bond campaign isn’t over after the vote, and it doesn’t begin when the community announces the proposal. Each measure is born out of its predecessor; each election is informed by the last.

The district’s actions after the vote, then, are a critical piece of their next campaign. If the measure didn’t pass, take heart. You have a new opportunity to connect with the community and learn: What did we miss? In the upcoming months, recommit to the listening process.

If the vote was successful, it’s time to start thanking your voters and advocates, as well as highlighting the progress you’re making on bond projects. Even if there aren’t any physical changes to post, the main goal here is to provide updates that show the district making good on its promises.

“It’s just about having transparency and showing the taxpayers that you’re doing what you said you’d do with the money,” says Superintendent Matt Kimball of Blue Ridge ISD in Texas. “And you’re doing it as efficiently as possible.”

During the entirety of the bond process, this means taking pains to—once more—put power back into the community’s hands, asking for input and inviting the community to celebrate your district’s growth.

After all, a community owns their district. This process of making and maintaining lasting impact and connections provides an opportunity for districts to learn from their communities, and for communities to learn from their schools.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!