Essential Work

How to Best Support Your Classified Staff

For the last 18 years, Sara Valerie has worked in campus catering at California’s Clovis Unified School District. It started out as a great “mommy job,” she says—she could be home in the afternoons and over holiday breaks with her two daughters. But now, years after her girls have graduated, she’s still there, and she plans to stay another 12 years. The reason why is simple: She loves the students.

“The best part of my job is seeing the children come in to get their breakfast every morning,” she says. “I’m the first person they see when they start their school day.” And Valerie, determined to make each morning a good one, greets every student by name. “We never know how their morning started off, so the way I greet them sets the tone for their entire day,” she says. “I’ve always treated each student the way I would want someone to treat my girls. In my mind, I’m a mom at work as well as at home.”

When the average person thinks about public education workers, they typically picture classroom teachers, not groundskeepers, custodians, or food service workers. But in every single school district, classified employees like Valerie are providing for students’ most basic needs while they’re at school: clean environments, comfortable conditions, hot meals.

These roles aren’t just improving students’ lives—they make school possible. It’s Maslow’s hierarchy: Kids must have their basic needs met before they can worry about learning. “If our bus drivers are not getting our children to and from school, we can’t hold classes,” says Dr. Jeff Butts, superintendent of Indiana’s Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township. “Our child nutrition workers are critically important. If our children are worried about empty stomachs, they’re not going to be focused on what’s happening in the classroom.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has further emphasized the importance of school support staff. In early 2020, thousands of food service workers, bus drivers, and other classified employees worked with their schools to provide and distribute meals to communities affected by school closures. That March, the California State Public Health Officer listed school support staff as “Essential Critical Infrastructure Employees.”

“In my 38 years of being a classified employee, that word—essential—has never been used to describe us,” says retired custodian Ben Valdepeña, former president of the California School Employees Association (CSEA). “But this year, schools realized that they could not survive without us.”

Unfortunately, schools all over the country are still attempting to survive without the number of classified employees they need. This will come as no surprise to most school leaders; if you’re not currently experiencing these staffing issues in your district, you’re in the minority. According to an October 2021 study by EdWeek Research Center, more than 75% of administrators surveyed reported “moderate” to “very severe” hiring shortages, especially for substitutes, bus drivers, and instructional aides.

“We have a labor shortage,” says Butts. “That means classrooms aren’t getting cleaned as much. Some schools are not able to transport all their children in school buses. Many of our paraprofessionals are being pulled into classrooms to fill in for teachers because we don’t have enough subs. All of those things have highlighted how valuable it is to have those individuals in our buildings and to have those positions filled.”

What’s behind the shortages?

As much as we wish this question had a simple answer, it doesn’t. There’s a complex web of factors, from inherent risks presented by the pandemic to hesitancy over masks and vaccines. But intertwined with those recent issues are more longstanding ones: respect, inclusion, culture, and compensation.

When we spoke with Kelly Post in November, she was working as a Special Education Behavioral Coach at a 39,000-student district in Texas. “I go to all 48 campuses, wherever there’s a need for additional training or there’s a behavior situation that people just don’t know how to handle,” she says. Post’s role, formerly titled “Senior Instructional Assistant,” entails helping students replace destructive behaviors with healthier ones—which is often much easier said than done. She’s trained and certified in Satori Alternatives to Managing Aggression, or SAMA, a method that combines verbal de-escalation with physical management techniques. “My partner in the district and I are usually the ones who come in and help when kids are harming themselves or others,” she tells us.

When the 2021-22 school year started, Post’s district was short 50% of the instructional assistants (IAs) it needed. Of course, the year of at-home learning in 2020-21 made the job much more difficult. “It’s really hard to do behavior coaching on a computer,” she says. “The kids just shut their laptops.” And it hasn’t gotten any easier as students re-enter their buildings. “All these kids coming back after COVID—they’re traumatized, even if they weren’t having trouble before,” she explains. “They’re all coming back from a hard place.” For some students, this emotional turmoil presents itself through behavioral issues.

However, when we asked Post what she believed was behind the extreme IA shortage, she didn’t blame the pandemic or even its fallout. “I think it’s something else,” she says. “Right now for our IAs and our district, I believe it’s the pay. You can make more money at McDonald’s—and there, nobody is going to hit or kick or spit on you,” she says. “You can’t expect them to work for less pay than they could make at a less strenuous job.”

Over the course of our conversation, other issues surfaced, too. “In the last couple of years, the appreciation for us has gone downhill,” she says. “I’m less included in situations, left out of more meetings. My last supervisor was really good at making sure we were part of planning and implementation. These days, it feels like we don’t have that.” It’s not just the lack of inclusion that bothers Post; it’s the effect it has on her students. “Sometimes I’m on one campus dealing with a big behavior issue on Friday, and then admin will want me to go to a different campus on Monday,” she tells us. “I really need to stay where I am, so the kids can see the continuation and the consistency of dealing with that behavior. But I’ve had trouble convincing administration of that.”

This January, Post left her position after 26 years with the district. In a follow-up email to us, she explained her decision: “The culture and concern for others that have always been part of this district are not there any longer.”

Of course, Post is only one person, and each employee has their own story, whether good or bad. But perhaps, from her experience, we can learn a few ways school leaders can better support—and retain—their classified staff.

Check your attitude.

At this point, it’s hard to deny how crucial classified employees are to the operation of your school district. But relying on your school support staff is not the same as respecting them. You or other members of your staff may be subconsciously viewing classified employees as “less than” without even realizing it.

In a 2020 New York Times article, political philosopher Michael J. Sandel draws attention to a series of studies conducted by social psychologist Toon Kuppens. When Kuppens and his team surveyed Americans and Europeans about a wide range of marginalized groups—Muslims, people with disabilities, people of color, just to name a few—they discovered that respondents with college degrees indicated more bias toward those without degrees than toward any other group. What’s more, Sandel points out, “the study also found that elites are unembarrassed by this prejudice. They may denounce racism and sexism, but they are unapologetic about their negative attitudes toward the less educated.”

As Butts puts it, “our schools are microcosms of our society.” Any prejudices that prevail outside the walls of your schools have the potential to creep into your classrooms. And in a profession where education is always top of mind and credentials are a particular point of pride, this bias against the less educated has even more potential to take root.

In a school environment, this rarely acknowledged bias has tremendous implications. Most positions for school support staff do not require bachelor’s degrees, and about 43% of classified employees have neither an associate’s nor a bachelor’s degree. This set-up—people with less formal education working in an environment centered on education—can lead to an unfortunate dynamic where classified employees are seen as less important, less intelligent, or less skilled than the certified teachers in their buildings. “There are still people out there who feel that if we don’t have degrees, how important can our jobs be?” says Valdepeña.

Many of the classified employees we spoke with referenced this dismissive attitude toward their positions. “Years ago, I had a superintendent tell me, IAs are a dime a dozen. We can get another one tomorrow,” Post recalls. “I’ve made it my goal to say, I’m better than that—you’re not going to be able to find another me.”

The truth is that you couldn’t pull just anyone off the street into one of your district’s classified positions. Bus drivers are required to have a Class B Commercial Driver’s License. Paraprofessionals are often certified in SAMA or other risk management methods. Food service workers are trained in child nutrition and menu design. According to data from the National Education Association, 43% of education support professionals are required to have a special certificate, and 29% need a particular license. Classified roles may not require a traditional college education, but they do require specialized skills and training.

Your classified staff members are no less capable and no less intelligent than your teachers and fellow administrators. Their expertise just lies in different areas. In a March 2020 issue of New York Magazine, journalist Sarah Jones hits the nail on the head: “It should be obvious now, if it wasn’t before, that there’s no such thing as unskilled labor.”

Of course, this is a thorny problem, and it’s not limited to your district. You can’t completely eradicate a pervasive cultural prejudice or even guarantee it won’t show up in your classrooms. But as a school leader, you can set a tone of respect in your schools.

A simple first step toward respecting classified staff is acknowledging them—in public, at staff meetings, in your communications. If you’re not careful, it can be easy to focus your all-staff meetings and other staff-wide events solely on teachers, making support staff feel like second-class citizens.

For Butts, it’s about being intentional. “I need to make sure that I’m talking not only about issues that are important to our teaching staff, but also about the issues that are important to our classified staff,” he says. “Every time I communicate how proud I am of the successes happening in our buildings, I have to acknowledge that everyone in those buildings is responsible for that. Yes, that means teachers and administrators—but it also means our child nutrition workers, custodians, secretaries, and paraprofessionals.”

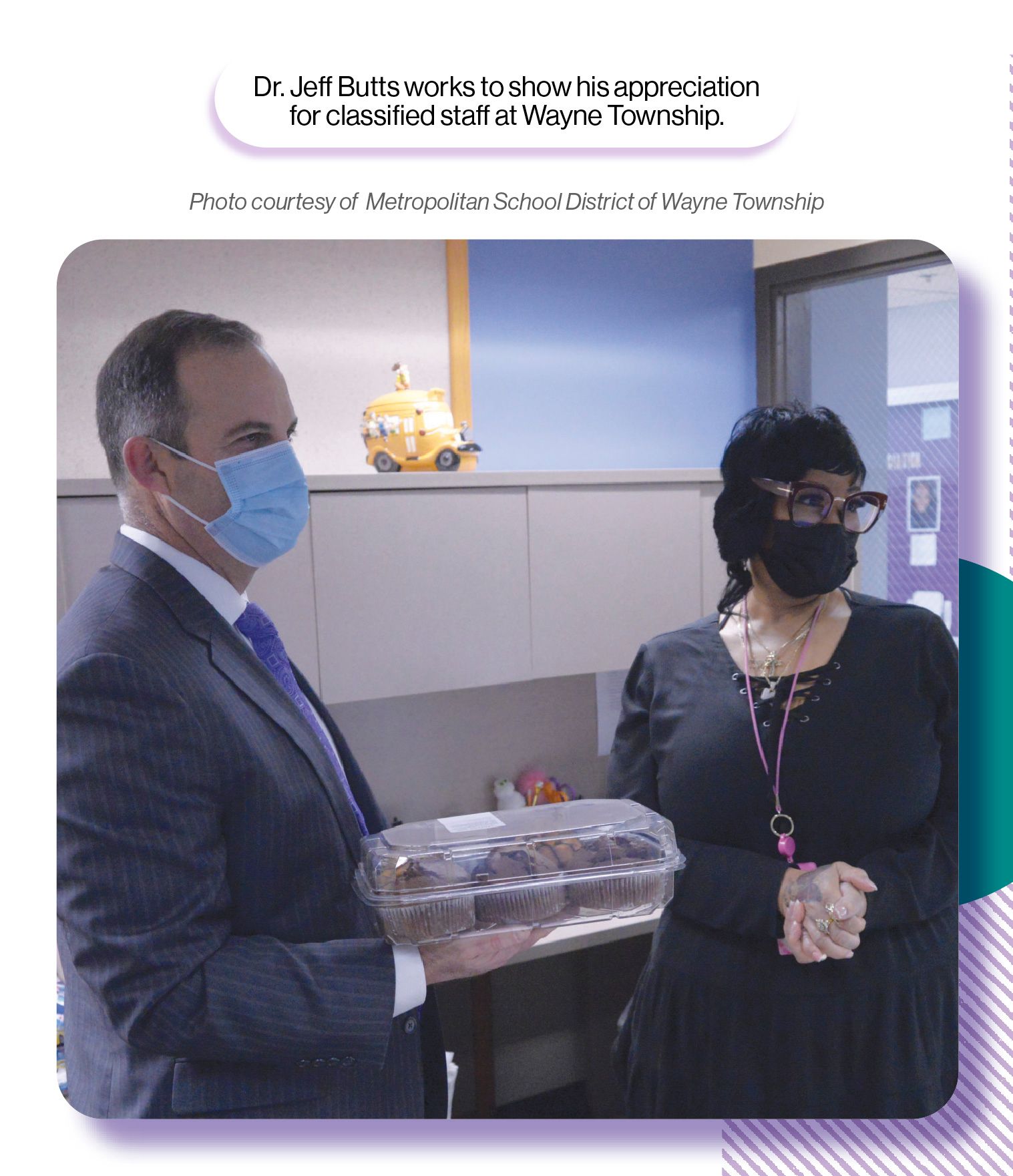

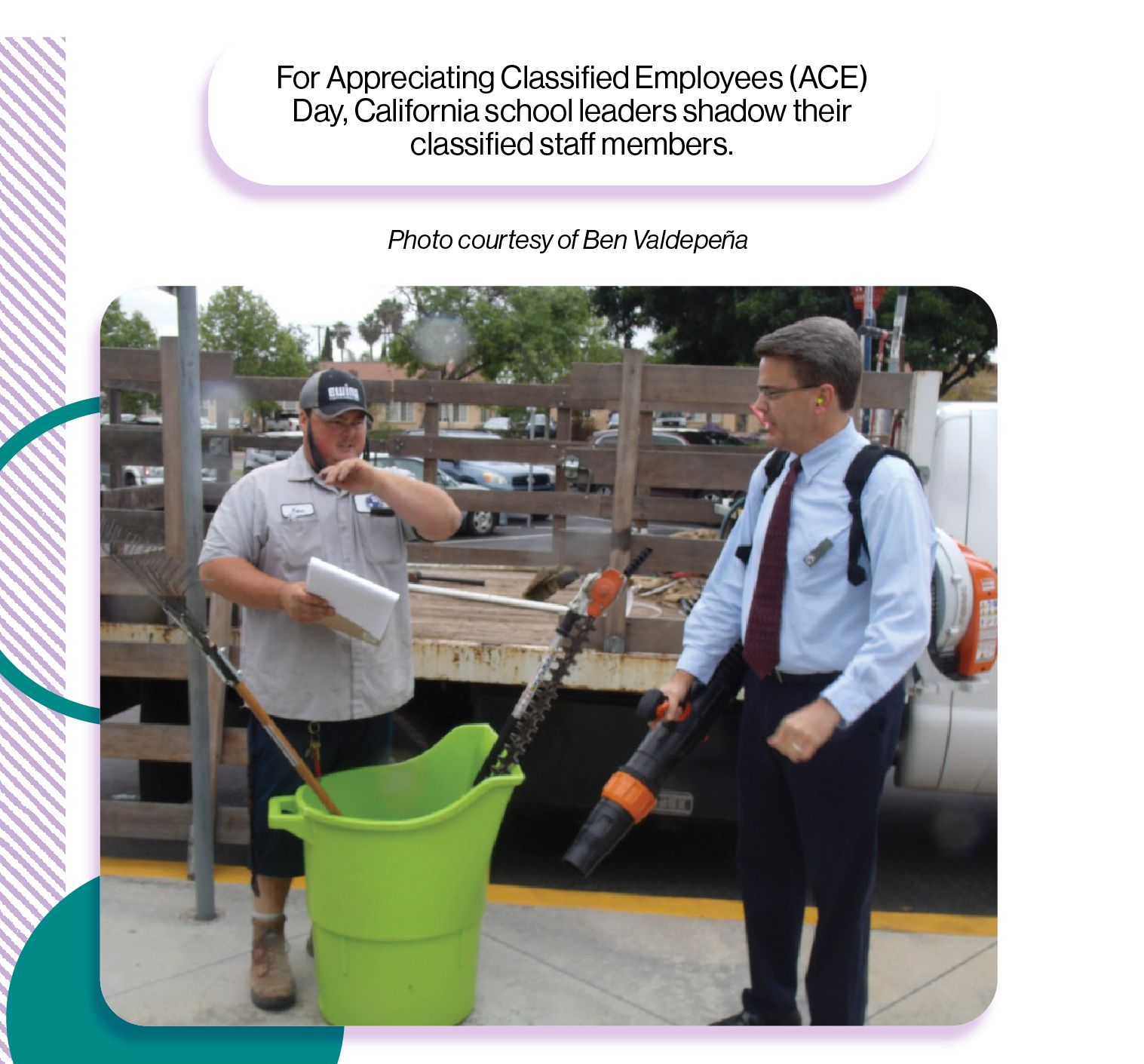

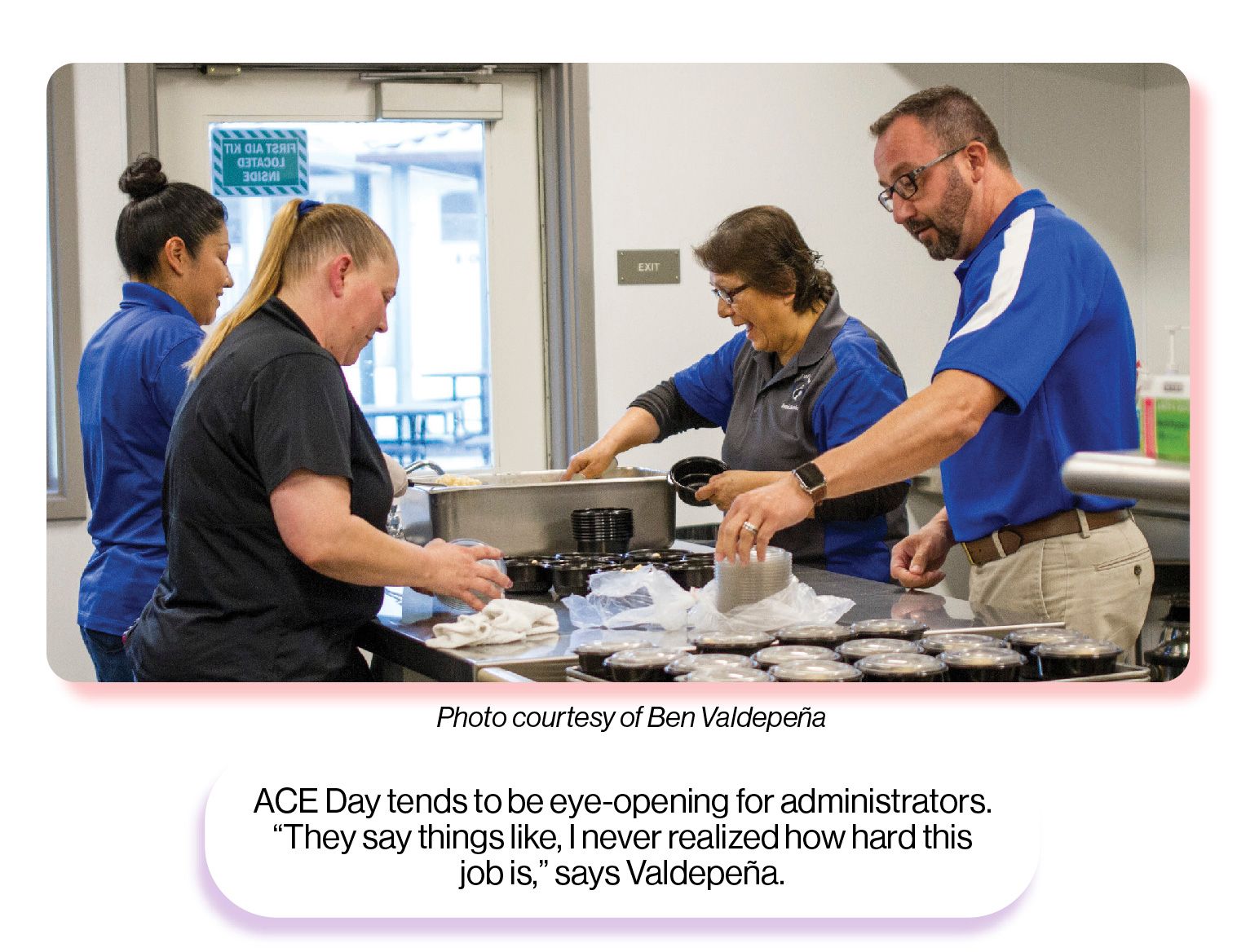

You might even find a hands-on way to turn those biases on their heads. Each year, the CSEA chooses 10 districts to hold what they call “Appreciating Classified Employees (ACE) Day,” an opportunity for administrators to shadow their support staff. “You might meet the grounds guy and start mowing lawns at 5:30 in the morning,” says Valdepeña, “or go work with a custodian, or serve lunches to the kids.”

For school leaders, this often leads to a striking revelation: I could not do this every day. “At the end of the day, the stories that you hear—there’s tears,” Valdepeña tells us. “They say things like, I never realized how hard this job is. I never realized how important it is.”

Whether you choose to implement some version of ACE Day or not, it’s crucial that you instill in your teachers and administrators the idea that no fellow employee is beneath them. Without that basic bedrock of respect, your classified staff cannot thrive.

Treat them as experts.

Respecting your classified staff is crucial—but it’s also the bare minimum. Once you’ve recognized them as professionals with unique and valuable skills, it makes sense to consult them on issues that pertain to their areas of expertise. However, many districts do not involve their classified staff in planning at all.

No matter how hands-on you are, no matter how many classrooms and campuses you visit per semester, you don’t see nearly as much of your schools as your classified employees do. While you keep a bird’s eye view of the entire district, these employees are often dealing with a single building or subset of students day in and day out. It’s possible, then, that they know what those buildings and students need better than you do. So why not ask what they think?

“You need your classified staff to help with planning because they will see things that administrators come up with that are wrong or that are really going to put a strain on the system,” says Valdepeña. He gives us an almost comical example: An administrator decided to serve buttered popcorn in his school’s cafeteria. “It literally looked like it snowed,” he tells us. “The popcorn was everywhere. The butter ruined the finish on the floor, along with the mops we were using to sweep it all up.” The night custodian even had to work outside his normal shift and spend four hours scrubbing the floors. “We could have stopped all that if we had been part of the planning,” Valdepeña says—”but quite often, we’re not.”

Including your classified staff in planning can not only prevent challenges, but also make a real difference for your students. Early in her career, Donna Mazyck, now the executive director of the National Association of School Nurses, changed a student’s life—and it all started with an attendance review meeting. “I was the first nurse at that school, and they were not accustomed to having a school nurse come to the attendance review committee,” she says. “But I had asked the principal if I could sit in because it was possible that I might have helpful information.”

During the meeting, administrators were discussing a high school senior with chronic tardiness and absenteeism. “She was in danger of failing,” Mazyck says. “So I volunteered to contact that student and find out what was going on.” She suspected that—as is often the case—this attendance problem might have its roots in health issues.

It turned out that this student was dealing with a perfect storm of factors. Unbeknownst to the school, she was struggling with untreated arthritis, making it difficult for her to get up in the mornings. What’s more, her mom—her only caregiver—worked the night shift, not getting home until after morning classes started. The family also didn’t have a car, so if this student missed the bus, she didn’t have a ride to school.

With this new knowledge in hand, the school worked to alleviate the student’s challenges and help her succeed. They were even able to secure much-needed health insurance for the family, allowing the student to receive treatment for the first time in years. The school counselor also changed the student’s schedule to make her first period class a study hall, in case she needed more time getting to class.

“It was just amazing to see that conversation turn around,” Mazyck tells us. “I used my nursing knowledge to reach out and realize that the issues were deeper than they appeared.” The student went on to pass and graduate—something that might not have happened had Mazyck been excluded from the conversation.

Show them they’re valued.

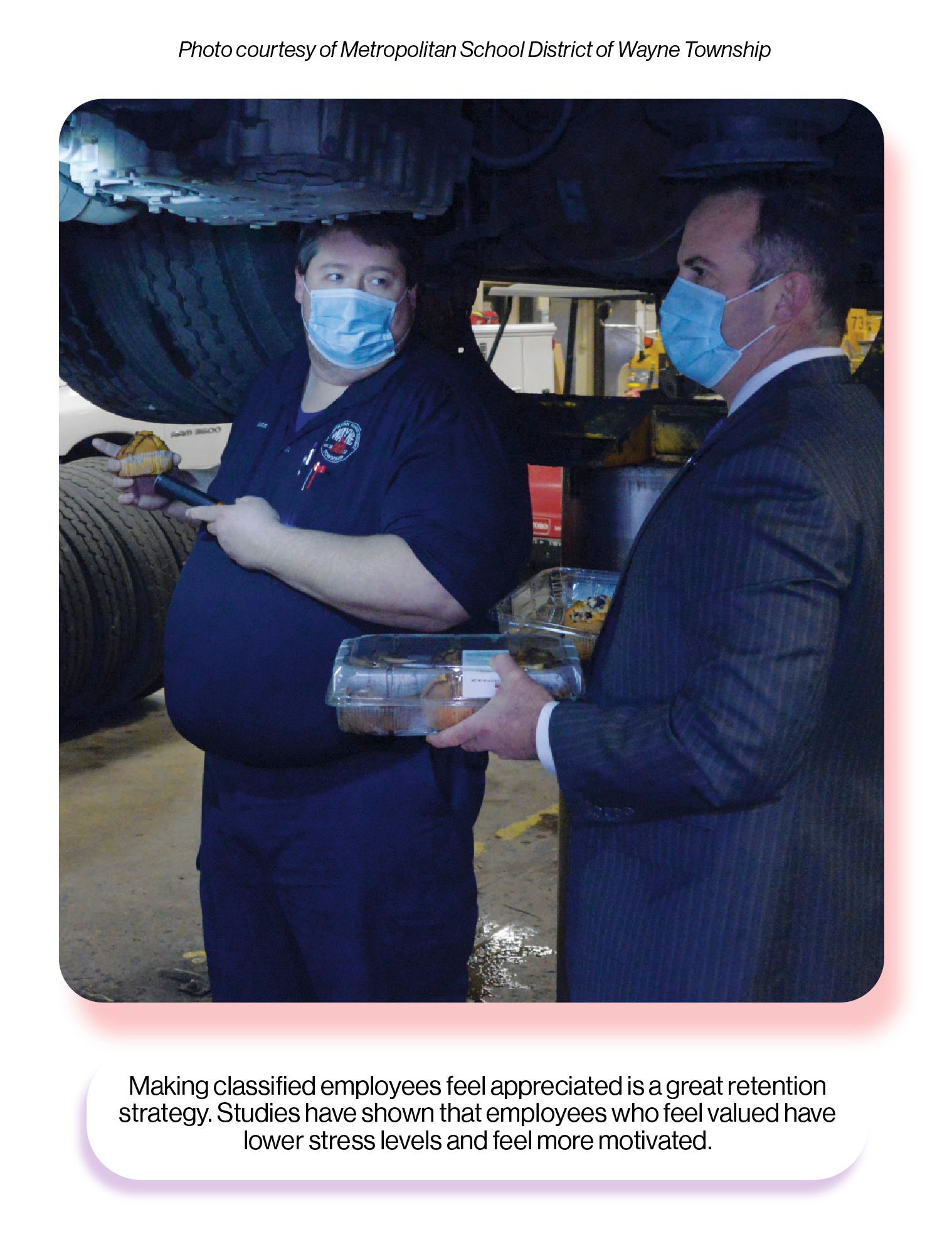

Basic respect and inclusion are great first steps toward a healthier environment for classified employees, but they’re just that—first steps. It’s crucial to also show your support staff that you appreciate and value them. This isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s also a great retention strategy.

According to data from business consulting firm Deloitte, companies with employee recognition programs experience 31% less turnover than those without them. Other studies have shown that employees who feel valued have lower stress levels and feel more motivated. So how can you show your appreciation? Here are just three ideas.

Don’t outsource for classified roles.

Research shows that the vast majority of classified staff members are deeply invested in their school communities. According to data from the National Education Association, 71% of educational support professionals live within the geographic boundaries of their districts. That number is a bit higher in Wayne Township—around 75%. “This is their community,” says Butts. “This is where they live. This is where their children go to school.”

The same study indicated that more than one in five classified staff members help with extracurricular activities, like coaching a sport or supervising an after-school club. About one-third have even given their own money to help pay for classroom materials, field trips, and class projects. “They are very loyal and devoted,” Butts says. Don’t they deserve the district’s loyalty in return?

For Butts, this means promising not to outsource for classified positions. “Our board has been very intentional and determined not to outsource, and our employees know that. We communicate that a lot,” he says. “They know that we value them, that we do not plan on outsourcing their jobs, that they’re going to remain employees of ours, that we’re going to take care of them.” This arrangement benefits Wayne Township as much as its employees. Classified staff employed by the district—not contracted through outside companies—have much more reason to invest in your school culture.

Provide fair compensation.

Of course, you also show your appreciation for your classified employees through the benefits and compensation you provide. Much like teachers, few school classified staff enter the profession expecting to get rich. “They know they’re not making a lot of money,” says Valdepeña “They’re here for the kids.” But unfortunately, as the saying goes, passion doesn’t pay the bills—and across the country, many classified employees are having trouble making ends meet.

These employees do have other options, and some of them may look more attractive. Since 2020, Target and Amazon have both offered a minimum wage of $15 per hour. McDonald’s is following suit, planning to reach an average wage of $15 per hour at its company-owned locations by 2024. By comparison, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly wage for a full-time teacher assistant in the U.S. is $13.89—meaning that half of all employees in that role make even less. No matter where you are, the competition for your classified staff is only going to increase; your wages should increase with it.

As we’ve mentioned, staffing shortages are complicated, and increasing pay isn’t a magic bullet. But no matter how much your classified employees love the students they serve, it will be difficult for them to stay in your district if they’re not making enough to live on. To successfully recruit and retain these critical staff members, it’s important to ensure you’re offering a living wage.

According to the most recent data from MIT, the living wage in the United States—the amount needed to meet a family’s basic needs—is $16.54 per hour, before taxes, for a family of two working adults and two children. But depending on your location and local costs of living, what constitutes a living wage could be higher or lower. You can use MIT’s Living Wage Calculator to find guidelines for living wages in your city or county. While you may not be able to meet this threshold immediately, the information this tool provides can help you justify higher wages to your board.

While it may seem like your hands are tied when it comes to budgetary constraints, many superintendents have found creative ways to use ESSER funds or even Medicaid to help pay support staff. In fact, according to a 2017 survey by the American Association of School Administrators (AASA), 68% of superintendents said their districts used Medicaid dollars to fund school nurses, counselors, and other health staff members.

Providing good benefits that offset some basic living expenses can also help make your district a competitive employer for classified workers. At California’s Clovis Unified School District, all support staff who work at least 20 hours per week have access to the district’s health plan, as well as an employee health center. Operated through a company called miCare, the health center provides sick visits, preventative screenings, disease management services, and more—all with no copay for employees or their dependents.

This arrangement benefits Clovis USD just as much as its staff, as the miCare model allows employers to buy health services at cost. Plus, when staff have easier access to primary care, they need fewer specialist and emergency visits, miss less work, and are healthier in general—which leads to greater productivity. It’s a win-win.

Here’s the bottom line: When it comes to cutting corners in your budget, your classified staff should not be the first expense on the chopping block. As we’ve seen over the course of the pandemic, your schools cannot run without them. What’s more, happy, well-paid employees are often your best advocates in the community. Remember: 71% of school classified staff live in their districts. Many of them are parents of your students. Their voices are a critical part of the overall conversation surrounding your schools—are those voices positive or negative?

Say thank you.

Sometimes, showing that you value your classified staff is as simple as thanking them. This small expression of appreciation can make all the difference in an employee’s experience—as can the absence of it. Valdepeña once faced a demoralizing lack of gratitude from administration after literally saving a child’s life. A kindergartener ran into the middle of the street, and a truck was barrelling toward him. Valdepeña pulled him out of the truck’s path just in time. “This shows you the value of classified employees: I walked into the office with this kid and nobody thanked me,” he tells us. “I was miserable for the rest of the day.”

Throughout your district, classified staff members are doing their essential jobs every day, and that alone deserves acknowledgement and appreciation. But they often go above and beyond their job descriptions, and your schools are better for it. “Spend time actually looking at your classified employees for what they do—not just what they’re supposed to be doing,” Valdepeña says. “You’ll find they’re doing a lot more.”

Recognize their impact on students.

According to research from The Search Institute—an organization that examines the roles of relationships in child development—students who have strong relationships with caring adults are more likely to be engaged at school. Similarly, a study in the Journal of Community Psychology found that when middle and high school students have strong relationships with adults outside their families, they exhibit less risky behavior and an increase in general well-being. For some students, it’s easier to connect with adults they don’t see as authority figures—like classified staff.

As a custodian, Valdepeña experienced this phenomenon often. “The kids would tell me things that they should have been telling their counselor,” he says, “and a lot of times, it was because I wasn’t wearing a tie. They felt more comfortable talking to me.” Once, a student confided in Valdepeña that she was pregnant; he took her to the counselor’s office and even helped her share the news with her mom.

Butts sees it at Wayne Township, too: kids confiding in and relying on educational support professionals. “Many of our classified staff develop relationships with our students, and those become mentoring relationships,” he says. “They sometimes fill the role of an adult that a child doesn’t have in their life outside of school.” A variety of factors could explain why certain kids feel more comfortable with non-teaching staff: race, class, or language barriers, just to name a few. “We have to be cognizant of the cultures that our students are coming from, the environments that they’re coming from at home,” Butts says. “Some of our students don’t feel comfortable going up to somebody in a suit and tie.”

For most classified employees, this dimension of the job isn’t an extra task on their plate; it’s the reason they come to work. “A lot of us, myself included, became classified employees for other reasons but stayed because we loved working with the kids,” says Valdepeña. As a school leader, it’s important for you to acknowledge and appreciate this aspect of a classified employee’s day-to-day work. They’re not just performing the crucial technical functions of their roles; they’re often changing lives—and being changed in return.

“I have had many titles in my life,” Valdepeña tells us, “but the title that I love most is Mr. Ben. That came from the kids, from their hearts. They see the value in Mr. Ben or whoever is taking care of them at school.”

Next time you see a member of your classified staff, look a little closer. See the skills they bring to the table, the time and effort they invest in certifications and licenses, the early mornings and late nights they spend keeping your school buildings running. See them as a resource, an expert with input you could use. See a human being, just like you, who needs to know they’re appreciated and valued. See what the kids see.

“Superintendents need to look at classified staff through the eyes of the children,” says Valdepeña. “Their worlds will change once they do.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!