The Labyrinth to Leadership

Are millennial educators making it to the top?

Anyone who has spent time in K-12 education leadership recently has probably noticed an elephant in the room at almost any summit or conference—increasingly high turnover at all levels. According to recent data by Education Resources Strategies, an education statistics firm, school superintendent turnover has already been high over the past decade—and it’s only getting higher. By March 2022, a record 26% of the nation’s largest school districts reported hiring a new superintendent in the previous two years.

All this shuffling at the top has led many in the field to wonder if hiring or promoting new administrators will become even more difficult, similar to what is already happening with teachers. After all, teacher recruitment and retention were problems long before the pandemic, and there are signs that it may only get harder as more and more classroom positions remain vacant.

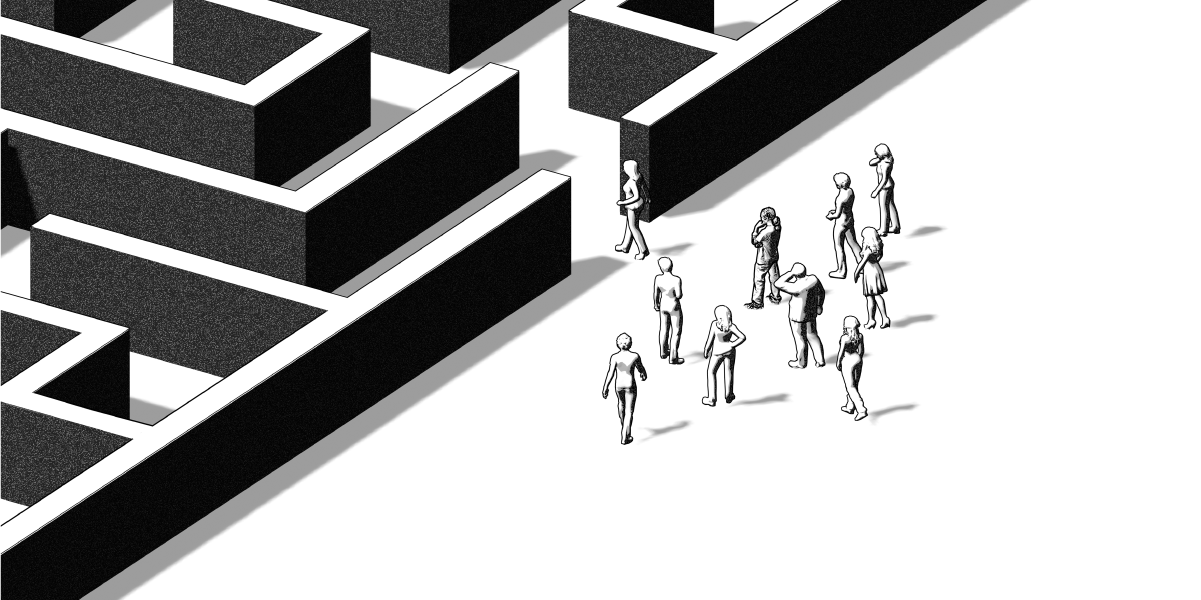

While it may seem like this problem will eventually trickle down—or trickle up—to education leadership, our recent research study shows that this may not be the case at all. While popular thinking has characterized leadership recruitment issues as a dried-up well, it seems more likely that potential leaders are getting lost in a maze of confused communication and inconsistent support.

In February 2022, we surveyed over 2,000 millennial teachers concerning their attitudes toward joining school leadership at all levels and their perceptions of the pathways that will help them get there. What we learned from analyzing the data and comments from our respondents is this: Interest in moving into leadership positions is astoundingly high among millennial teachers. In fact, your next school leaders could be right in front of you.

Where are the future supers?

Let’s talk a bit about our research study. In surveying millennial teachers, we wanted to answer a few questions. First, how do these educators, many of whom are now seasoned professionals, feel about moving into leadership positions? Secondly, are there supports in place— leadership pipelines, mentorship programs, or even casual administrative support—to ensure that this transition happens? Finally, what impact could this new generation have on the demographics of school leadership as they assume power?

You might be wondering why we chose to focus our efforts on millennials. In some ways, we designed this study to be a follow-up to our 2019 study, “What Do Millennial Teachers Want?” As many millennials are now in their 30s and 40s, they are no longer rising young professionals; at their current ages and experience levels, they’re much more likely to be ready for leadership.

While recruiting millennials remains a concern for education leaders, retention is just as important—because without them, where will your next generation of leaders come from? Given that millennials are unlikely to stay in districts where they don’t see a path forward for their careers, leadership opportunities are an absolute necessity for retaining millennial teachers.

When we began our study, our team wondered if the intense nature of current K-12 education leadership might result in a diminished number of aspiring leaders. After all, administrators from principals to state superintendents have spent the last two years serving as the spokespeople for increasingly contentious decisions.

Notes on our research:

When we refer to leadership in this survey, we are specifically referring to K-12 administrator position, either at the building level or at the district level. We acknowledge and celebrate that classroom teachers often lead from the seats they're in, but for this survey, we are referring to school administrators such as principals, assistant principals, district leadership of any kind, curriculum coordinators, and equivalents—but not lead teachers, counselors, or coaches.

A leadership pipeline was defined in our survey as a formal program that identifies, builds, and supports top talent within a district with the purpose of promoting internal hires into administrative positions. Similarly, a mentor was defined as a colleague who often has more experience in the field and helps support professional growth.

In our research, we define millennials as anyone born between 1980-1995.

What we found, though, was that millennial educators—especially those with more than a year of experience in the classroom—continue to show interest in becoming leaders. In our first study of millennials in 2019, we found that one of the top five qualities millennials desired in new teaching opportunities was the potential to rise through the ranks. Our new data suggests that this continues to be true. Respondents were asked, Are you interested in moving into school administration? The vast majority of survey participants—over 73%—said that they were either “very” or “somewhat” interested.

What this means is that for every four teachers, three are interested in some kind of leadership. But how high do they want to go? To find out, we asked respondents who were interested in leadership, What is the highest level of administration you aspire to reach in your career? The most popular answers were district-level leadership other than the superintendency (36%) and building-level leadership (35%). It is worth noting, though, that nearly one in five interested educators said they aspired to the superintendency itself (Figure 1).

Generally speaking, our respondents were interested in moving into leadership regardless of how long they had been in the classroom, although this interest did wane somewhat over time. A staggering 76% of new educators—teachers with fewer than two years of experience—were interested in a future administrative position. This number decreased only very slightly in educators with three to five years of experience; 75% of these educators expressed interest in moving into leadership. Teachers with more experience were generally less interested in leadership. Even still, 34% of seasoned educators with more than 15 years of experience reported that they were “very interested” in moving into administration.

Our survey was clear—teachers at all levels of their careers are interested in leadership. Furthermore, 67% of our survey respondents said they would rather pursue a leadership position in their current district than move to another—so those interested are likely already in your buildings. If you listen to these emerging leaders and provide the support they need to make it, the search for your next generation of administrators could be a natural passing of the torch, instead of a frantic national search for the right candidates. The key, of course, is retaining your future leaders until you’re ready for them to move into positions of power.

Your leaders are right in front of you.

If your leaders are already in your buildings, how do you make sure they end up in positions of power when the time is right? The answer is complex, but, according to our study, there are two places to start: leadership pipelines and formal mentorship programs.

In our survey, we asked respondents three questions around these topics:

- Does your district have an established leadership pipeline or a robust process for identifying future administrators?

- Does your district have an established mentorship program with assigned mentors, aside from those intended for novice teachers?

- In your experience, is mentorship (either informal teacher relationships or formal programs) in your district an effective tool for teacher growth?

In general, responses were very positive. Over 70% of respondents reported the presence of some form of leadership pipeline in their districts (Figure 2). Additionally, the vast majority (65%) of educators reported that their districts have some kind of formal mentorship program that includes all educators. Mentorship was viewed favorably by our survey participants, even though roughly a quarter of districts do not have formal mentorship programs.

Overall, 73% of respondents expressed that mentorship, in general, was used effectively in their districts, regardless of whether or not they had formal mentorship support. It would seem that even when there are no official assignments or programs, mentorship is still a crucial building block of teacher development.

What does this mean for you and your district? First, you must be prepared to use these tools—leadership pipelines and mentorship—to your advantage. If you’re among the 66% of districts that have a leadership pipeline in place, you’re on the right track. If you’re in the third of districts that don’t, this should be your first step.

Building a leadership pipeline may seem intimidating if you've never had anything like it in place, but plenty of districts have laid the groundwork for you. In fact, the Wallace Foundation, an educational philanthropy group based in New York, published a guide in November 2021 for building leadership pipelines titled "Principal Leadership in a Virtual Environment." It details not only how to build a sustainable pipeline, but also how to use federal funding to do so. This guide can be found on AASA's website under the Wallace Foundation Resources tab.

Mentorship, on the other hand, is probably happening within your district—either officially or unofficially— whether formal programmatic support exists or not. Collaborative relationships among teachers mean that mentorship, including peer mentorship, happens naturally as teachers work together to hone their craft. It is up to you, however, to take these relationships to that next level. As has been demonstrated by previous research, mentorship of all kinds can be a critical component of teacher success and support, especially among people of color.

We won't be going in-depth into building mentorship programs, but there are plenty of resources out there, such as AASA's "Six Steps to an Effective Mentorship Program." While most districts have some kind of mentoring program for new teachers, research shows that teachers at all levels benefit from mentorship. Just like quality classroom teaching, a strong mentor-mentee relationship fosters learning on both sides.

Leadership pipelines, on the other hand, can’t exist without institutional support. Although these pipelines aren’t inherently expensive, they often require a lift that can only happen at the executive level—and that starts with you.

Lost in the Maze

If your future leaders are already in your district, then where are they? We initially wondered if leadership positions weren’t being communicated internally, but it seems this isn’t the case. We asked respondents, When there are administrative openings, are those positions and their requirements clearly communicated to current staff districtwide? About 78% of those surveyed said that their districts communicated new administrative openings either “very clearly” or “somewhat clearly,” which is definitely a step in the right direction (Figure 3). But communicating the availability of these positions is not enough; you must also provide the support necessary to prepare your educators for that next step in their careers.

This is especially true if you are aiming to increase diversity within your district. Research shows that women are more likely than men to view themselves as unqualified for positions that they are, in fact, qualified for. Similarly, people of color are less likely to be hired for jobs that they interview for compared to their white peers, regardless of their other qualifications.

Doing this outreach on your part by personally identifying a diverse group of educators with leadership potential is one way to ensure that your pipeline is both accessible and welcoming to everyone. Inclusivity is an active process; you cannot make positions accessible without addressing your own system’s inherent barriers. Building a leadership pipeline that works to correct for any institutional biases is one way to make this happen.

Millennial educators want (more) opportunities.

If you’re recruiting experienced teachers right now, you are likely still recruiting millennials, even as the first Gen Z teachers begin to join the workforce. As we know from our previous research in 2019, opportunities for career advancement are vital to millennials searching for their next position. If seasoned teachers are leaving your district for others, chances are that they didn’t feel as if they had adequate opportunities for advancement. Additionally, some research suggests that the presence of teacher-leadership pipelines increases retention and even the overall quality of a district’s instruction.

Of course, knowing that three-quarters of your teachers are interested in leadership doesn’t mean that all of those teachers will—or even want to—leave the classroom. It’s up to you to find out what drives interested educators to seek out leadership. Is it recognition? A desire for higher compensation? Or is it something more complex, like a drive to hone their craft or to build upon the leadership skills they’ve gained in their years in the classroom?

Understanding this why often means building variations into your leadership pipeline that provide opportunities for everyone—supporting both teachers who want to become administrators and those who simply want to grow. For the latter group, consider options that push them to become true master educators, such as pursuing National Board Certification or taking advantage of teacher leadership programs associated with local universities.

Varying your leadership opportunities can benefit your district’s efforts in both recruitment and retention. Wes Watts, superintendent at West Baton Rouge Parish Schools in Louisiana, has helped spearhead the implementation of a leadership pipeline program with two differentiated cohorts: LEAD West and TEACH West. While both paths focus on leadership development, LEAD West targets educators who want to eventually move into some kind of administrative or instructional leadership role, while TEACH West supports those working toward true pedagogical mastery.

Barbara Burke, Director of Human Resources and Staff Development at West Baton Rouge, has helped design both programs. “We realized after our first cohort that we needed to support all of our staff, not just those who want to leave the classroom,” Burke explains. With support from Associated Professional Educators of Louisiana (A+PEL) and Louisiana State University’s School of Education, both cohorts include one-on-one leadership coaching, ensuring that everyone is supported as they grow into the next stage of their careers.

Watts and Burke say the program has already had an enormous impact on their district—even though they are just now closing out their second cohort. “We are already having people move into leadership roles that we would have previously had to search or do principal recommendation for, including our newest Career and Technical Education Coordinator,” Burke explains.

Do they know you have a pipeline?

It is not enough just to have a leadership pipeline—every single staff member has to know about it, from first-year teachers to veterans inching toward retirement. It doesn’t help your district if you are hyperfocused on, say, first and second-year teachers. While you want these educators to be engaged and excited as they launch their careers in the classroom, you also want to involve more seasoned staff.

Our research shows surprising differences in awareness of leadership pipelines depending on tenure. While knowledge of leadership pipelines generally increased among more experienced educators, it peaked with teachers who had been in the classroom for 6-10 years and dropped after that. Only 60% of those who have been teaching for more than 15 years said they knew of leadership pipelines in their districts (Figure 4):

We also asked teachers, Have you ever been personally encouraged by an administrator to pursue an administrative position? Teachers with 6-10 years of experience were most likely to report being approached by their administrators (69%). This makes sense given that these teachers may be far enough along in their careers to be ready for a career change. Unfortunately this figure, too, drops off for teachers who have taught for longer.

What does it mean that more seasoned educators are most unaware of—or even overlooked by—leadership pipelines? As we reviewed this data, it reminded us of findings from our Winter 2022 research study, “Who Speaks For Your Brand?” In that survey, we found that the longer an educator had been working in a district, the less valued they felt by their administrators (Figure 5). While these findings about more experienced teachers could be unrelated, it is striking to consider that some of the most seasoned educators in your buildings could also be the most disaffected.

Disengaged teachers with low morale are unlikely to go looking for additional responsibilities—even if their wealth of experience means that they are uniquely qualified for the job. After all, they’re just trying to survive and avoid burnout. This is especially troubling as those same veteran educators, millennials or not, are the teachers you likely rely on to set academic and cultural norms for new hires.

Once you have an established pipeline, you need to do the work to make sure that your pipeline is an enriching experience for everyone—not just more work. West Baton Rouge, for example, supported their leadership cohort by paying an hourly stipend for after-hours meetings. This could also look like offering teachers in leadership pipelines additional planning time to collaborate with their cohorts. As you know, teachers already struggle to find enough hours in the day. Leadership pipelines should help alleviate burnout, not present additional expectations for a tired but passionate teacher.

Millennials may fear the downsides of education administration.

Even respondents who were interested in becoming administrators still had their reservations about leaving the classroom. We asked interested teachers, What appeals to you about an administrative position? Do you find anything about school leadership unappealing? Their answers revealed many threads of apprehension, including an unwillingness to leave behind daily interactions with children and legitimate fears of being held accountable for student testing data or other factors that may feel out of their individual control. Dozens of respondents also reported disinterest in interacting with families and other potentially tedious or difficult aspects of the job.

Similarly, we asked those who expressed disinterest in leadership, What do you find unappealing about moving into an administrative position? Is there anything about school administration that you WOULD find appealing? Some of these comments suggested how the current political climate could be impacting internal perceptions of education leadership. “I enjoy my content area and guiding young scholars,” one respondent reported. “I am not and never have been interested in an administrative position because of the politics involved.”

Some educators surveyed also worried that being an administrator would mean more work altogether. “Being within an administrative position requires more hours as well as dedication,” wrote one participant. “You are responsible for a lot of people. It’s important that you are on top of things when it comes to your staff and students.” Another respondent echoed this concern, as well as the expectation that school administrators must always be accessible. “I need time off the clock and time spent with my family,” they wrote. “I have family members who were school administrators at all levels, and they were constantly interrupted by phone calls and emails. I want separate work and home lives.”

While superintendents’ responsibilities vary by district and broad national change seems unlikely, the industry seems to be inching toward becoming more family-friendly as school boards are forced to work harder to recruit candidates. Recent contracts for superintendents have made local news for including more paid leave, opportunities for remote work, and even substantial periods of sabbatical leave—all of which were practically unheard of prior to the pandemic. Will this be leveraged for meaningful change? It is uncertain, but there is hope that this progress will continue as the nature of work evolves, not just in American classrooms, but in the country as a whole.

Current paths to the superintendency are inequitable.

When we set out to do our research, we wondered how the gender and race makeup of an emerging generation of leaders compared to recent research presented in the 2020 American Superintendent Decennial Study. While AASA’s data has consistently shown slow and steady progress toward education leadership’s increased diversity—there are more women and people of color in the superintendency now than ever before—our data showed that there is still work to be done to keep this progress moving forward.

Although the millennial educators in our study were generally very diverse, we saw evidence that men continue to be overrepresented in education leadership. When we asked respondents whether they’d ever been personally encouraged by an administrator to pursue an administrative position, men and women answered very differently. While 76% of male educators reported that they had been approached regarding their leadership potential, only 57% of women said the same. This is especially troubling given that nearly 76% of teachers are women, something that is not reflected in the gender makeup of education leadership nationwide (Figure 6):

The causes of this disparity are difficult to solve without deep, systemic change. However, formal programs like leadership pipelines address the first barrier toward more equitable representation: access to those in power and an understanding of how to become a person in power.

While implicit bias is impossible to avoid on an individual level, this doesn’t have to be true of systems, especially when they are designed with equity in mind. Without a formal pipeline in place, it may not be obvious if women are being encouraged toward leadership less often than men. That disparity will be much more apparent if your upcoming leadership cohort is mostly white men.

What happens if nothing changes?

Maybe you’re in a rural district with few resources and even fewer leadership opportunities. Maybe you’re in a large, sprawling district where individual campuses hire and recruit their own leaders. There are many reasons a district might lack a leadership pipeline, but in order to recruit and retain high-quality teachers and leaders, you can’t let those reasons stop you. If your district is one of the 30% that respondents report may not have leadership pipelines, your next move is to make that happen, no matter your circumstances.

The research is clear: There’s heartening potential for a huge shift in what education leadership looks like in the United States. But there is also reason to fear that this shift might not happen at all. In many parts of the country, teachers are burning out faster than they can be certified, even given increasingly innovative alternative certification programs.

A strong district needs to have strong leadership at all levels, from the classroom to the district office. It is your charge, as superintendent, to create an environment in which all kinds of leadership can flourish. If your district is a great place to work where personal and professional growth is prioritized, it will likely be able to thrive no matter the national climate.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!