Dr. Tiffany Anderson: Sneakers to the Ground

Superintendent Dr. Tiffany Anderson is leading a new legacy of learning in Topeka and beyond

Once again, there’s history being made in Topeka, Kansas. The school system once at the center of 1954’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education case is now being led for the first time by an African American woman—and she’s well aware of the powerful message that sends her students. “Just seeing me walk through the door changes mindsets,” Dr. Tiffany Anderson tells SchoolCEO. Anderson has a long legacy of changing lives, along with an unrivaled passion for service.

And though she’s spent a majority of her 27 years in education as an administrator, she still considers herself a teacher. “The title is superintendent, but, ultimately, I’m teaching and learning everyday,” she says.

When we sat down with Anderson, her humility spoke volumes—she keeps her thoughts and her heart centered on students, especially the most vulnerable. Through four superintendencies in three different states, she has facilitated and overseen transformative initiatives for tens of thousands of kids, all while showing up for her communities at every turn. With her business suit and signature white tennis shoes always on, this daughter of two retired pastors says service and purpose are ingrained in who she is. Fortunately for many students and counting, she’s a superintendent.

Dancing in the Puddles

Many years before her time in Topeka, Anderson—a St. Louis native—became the youngest principal in the state of Missouri at just 24 years old, at an inner city school where she says nobody wanted to go or work. “When I first toured the building, it rained inside the classrooms,” she explains. “I asked the teachers how they taught this way, and one said, Around the buckets, baby—how would you teach?”

Despite her respect for the teachers’ grit, Anderson wanted to change this acceptance of low standards and outcomes in the school, so she got creative. “You can either complain about the rain or dance in the puddles—I choose to dance in the puddles,” she tells us. In the case of Clark School, the issue was literal puddles. “I videotaped all of the mold and disrepair and rain in the building, and I put a label on it reading The Holiday Program at Clark School, because I knew that would get the attention of the St. Louis City administrative staff,” she explains. “In a district that size, you can’t assume they know what hundreds of buildings look like. But they saw the tape, and they were horrified. So they began fixing stuff.”

This would only be the beginning of Anderson’s work to improve schools. She also knocked on doors in neighborhoods surrounding the school, inviting residents on tours to see where their kids were learning. Support for the school soon began pouring in. During her time there, Clark School would see significant improvements and has now become Clark Accelerated Academy. Soon after, she led initiatives to reduce achievement gaps and increase graduation rates for students of color as the assistant superintendent of Rockwood Public Schools in Missouri. Then, Anderson was ready to take her brand of caring leadership to the superintendency. She started in Virginia’s Montgomery County Schools, where she refocused the district on college preparation. Under her leadership, every Montgomery County school earned accreditation.

Back in her home state, Anderson briefly and successfully ran an urban college prep academy before taking over as superintendent of Jennings Public Schools. Jennings, a suburb of St. Louis near Ferguson, was in desperate need of Anderson’s knack for community building. There she once again proved that high-poverty schools can also be high-achieving ones.

While in Jennings, Anderson oversaw initiatives to install free washers and dryers in district schools, open a community food pantry for families in need, and partner with Washington University to open a medical and mental health clinic inside

one of the high schools. The successful academic results of addressing the community’s poverty are impossible to ignore. By the time she left Jennings, the graduation rate and college placement rate were both 100%. “That’s almost un-

heard of in a school with 100% poverty,” she says. Her work to uplift and support students and families experiencing poverty—while simultaneously improving academic outcomes—garnered national attention. In 2016, NPR praised Anderson “for embracing a holistic approach to solving the problems of low-performing students by focusing on poverty above all else, and using the tools of the school district to alleviate the barriers poverty creates.”

For Anderson, it’s vital that her work serves as an example to others. “We have to uplift these models of success—know who they are and where they are and talk about them,” she says. “That inspires everyone else who’s trying to find models they can learn from.” That, she adds, changes mindsets. “When someone says that public schools aren’t, we should be able to say public schools are—they are great, they are innovative, they are amazing, and let me show you a few,” she says. “We should be able to do that without hesitation.”

Changing Mindsets, Teaching Purpose

Anderson is constantly working to shift perceptions in her district to yield positive results. But that starts with understanding. “It’s all about relationships,” she tells us. “Kids will work for you if they trust you; they won’t if they don’t. Adults are the same way. I tell people, Seek to understand in order to serve. In order to change how I think or at least give me another perspective, you have to understand me, and I have to understand you.”

She carried her work to Topeka Public Schools (TPS), where in 2016 she became the first African American woman ever to lead the historic district. “That, in and of itself, changes a lot of minds about what a superintendent looks like in Topeka, Kansas,” she explains. “I am one of two black women superintendents in the entire state—that changes mindsets, too.”

To make sure the district is serving all students, Anderson and her staff spend a lot of time looking at and addressing equity gaps. “Sometimes society might give an image of who you are that really isn’t who you are,” she says. “Our role is to help make sure you’re uplifted and supported in ways that allow you to see that you are pretty amazing and brilliant, and that your purpose in life is one that no one else can define for you.”

TPS starts by teaching students about purpose. “We spend a lot of time looking at things like race, gender, and equity gaps,” Anderson tells us. They even start with kindergarteners, asking them things like, What’s your why? “When you’re grounded in your purpose and your beliefs, you further know who you are, why you’re here, and why you get to do what you’re doing,” she says.

Currently closing out her fourth year in Topeka, Anderson regularly uses her commute to listen to the words of others who inspire her. “I listen to a sermon at least twice a day, once on the hour drive to work and once on the way home, and normally one of those is by Martin Luther King, Jr. In multiple sermons, he says, I can do well if you can do well, and you can do well if I can do well—we’re all interconnected,” she says. “Literally, your success is connected to me. Everyone reading this right now is connected in terms of making sure we uplift one another. Changing mindsets has a whole lot to do with understanding that for kids. How they succeed or fail is going to impact their teacher, their community, economic prosperity, and our nation. We can’t do well if our children don’t do well, and vice versa.”

Purpose seems to be an unstoppable driving force for Anderson. Not only does she serve as Topeka’s superintendent, but she’s also a lifetime member of the NAACP, is an adjunct college professor in both Kansas and Missouri, and was most recently appointed by the governor to the Kansas State Board of Education’s Postsecondary Technical Education Authority. On top of all that, she finds time to write about topics close to her heart, like ending the school-to-prison pipeline. “The purpose of my job is to advocate for the marginalized,” she tells SchoolCEO. “To be a voice for the voiceless, and to ensure that we are a better world tomorrow than we are today.”

Building a Human Experience

In Topeka, which has a 78% free and reduced lunch rate, Anderson has incorporated several strategies based on her equity work in Jennings, including a mobile food pantry, a mentor program for high school seniors, and a school-based comprehensive healthcare clinic at Topeka High School through a partnership with the University of Kansas Hospital. Just like Jennings, the district has also added washers and dryers to 18 schools for parents to use in exchange for volunteer work.

This good work not only helps the community, but also has a positive side effect: earning trust and support for the district. “We spend a lot of time really looking at what we say, what we do, and how we message that,” she tells us. “Pretty much everything that works in a classroom as it relates to being a teacher leader—branding what you do, building relationships, making sure engagement and learning are at their highest levels—carries over into district-level experience. That’s really a key component of what we do in transforming the school or community, really looking at how we can build a human experience.”

That experience can look many different ways in a district like Topeka, but Anderson says it still goes back to nurturing relationships in the community. “I believe schools are a business as well,” she tells us. “It’s the business of educating students. So when we talk about building a quality experience, we want to make sure that our students and our staff know they belong and know we love and care about them.”

One successful way Topeka Public Schools proves they care? Something they call the Dream Team. “If you have an issue or challenge and have a dream for something, you can submit it,” Anderson explains. “Our Dream Teamers—all volunteers from the central office—work to make dreams come true for people in the community. All of that’s focused on experiences that let our community know we care very much about them as members of our Topeka School family.”

A relatively new initiative, the Dream Team attempts to fulfill dreams across the district. For example, a district custodian’s home was recently damaged in an accident. “The repair costs exceeded what his insurance check would be,” Anderson says. So the Dream Team approached both a local financial firm and a construction company for help. “Within days, the two of them together rebuilt the side of the home, renovated it, and bought new furniture,” she adds. “That’s one of our larger dreams. It has just been wonderful.”

At the start of each school year, TPS hosts an all-staff convocation at Washburn University. This past year, they invited the custodian to share his Dream Team story. “You had 2,500 staff members being reminded of who we are,” Anderson says. “We recognize that we’re all connected and only collectively can we do this work.”

On a smaller scale, a Topeka teacher recovering from surgery wasn’t able to decorate her classroom before school started, so the Dream Team stepped in. “They showed up before she arrived the very next morning and decorated her room in the way she was hoping,” Anderson says. Even though the dreams can range in size and scope, Anderson says it’s a special way to let people feel seen and heard.

“We want to make sure that you feel special and that you have an experience as a result of connecting with Topeka Public Schools,” she explains. “It’s very similar to companies that are highly successful by always working to make a better product or create an experience that’s more engaging and inviting. We as public schools need to do the same to make sure that learning is at its highest levels—and that our parents and those without children in school become partners and have avenues in which they can really have that experience.”

Creating trusting relationships goes beyond the TPS staff. The district also works to partner with others to help students and community. “Once you build strong, trusting relationships, you really have the opportunity to make changes and, ultimately, move performance,” Anderson explains.

“Schools cannot accomplish what we need to accomplish alone, nor should we want to,” she says. “Public schools are the driver for economic vitality locally and nationally. So if you want to move the economic needle and have prosperity in your community, you really need partners to be engaged and to understand the why behind what you do.”

One example of these successful partnerships is a project called Impact Avenues. Working with local businesses, housing corporations, the City of Topeka, and the Kansas Department of Children and Families, this initiative provides housing and support services for students and families experiencing homelessness. “In Topeka, we have 400 to 600 homeless students in any given year,” Anderson tells us.

During her first year in the district, she required all her principals to spend one hour a month at their local homeless shelter to mentor people in the community and to learn about generational poverty. “It was so powerful,” she says. “Our graduation rate at our highest-poverty school eliminated the achievement gap last year, so close to 90%—black students and white students—are graduating at the same rates now, which is a first for Topeka.”

In addition, the college placement rate in TPS has continued to climb. “In my last district, that rate is now 100%, so we know we can get there—we’re just a little bit larger than Jennings,” Anderson explains. “It shows that this work can be replicated and that building relationships and bridges is a key component in ensuring success for everyone.”

Interrupting Poverty with Opportunity

If you walk through the halls of Topeka Public Schools today, they won’t look anything like they did in 1954. “Schools have changed so much even just in my 27 years in education,” Anderson says. Despite widening income disparities—the free and reduced lunch rate is now above 70% nationally, indicating there’s more children living in poverty—Anderson says there’s something substantial helping make up for gaps in equitable learning. “Technology now rules the day,” she tells us. “What might surprise people is the innovation occurring in our schools on a daily basis and the tremendous amount of talent and creativity in our classrooms.” Technology in the classroom levels the playing field, so to speak. “No matter how much money you do or don’t have, teachers are able to make learning exciting and fun,” she adds.

In terms of class time, Anderson says the old ways of sitting in rows and staying quiet are long gone. “Now it’s an active and productive classroom where you can hear and see learning happen,” she tells us. “Today, you’ll see a great deal of personalization and student engagement in education. Classrooms are a dynamic place because we know so much more about the brain and how students learn.” We also know a lot more about culturally relevant pedagogy, Anderson tells us. “Schools today give you hope, they inspire you, and they help you look for what’s possible for the future.”

The future is a focal point in Topeka Public Schools. The district currently offers a variety of career pathways, with up to 60 college credits available through courses in its high schools. “You can get an industry credential or you can graduate high school with your associate’s degree,” Anderson explains. “Every public school should have those opportunities—with virtual education, concurrent credit, and colleges partnering with public schools in some amazing ways, there is no reason why students should not be able to be prepared for college and career.” Anderson is careful to say “college and career,” because she believes students should leave their options open for the future.

“Individual plans should be created at a very early age,” she argues. “When students enter elementary school, we have career fairs and we talk about what they want to be and where they want to go. That should be drilled down to individual plans of study, at elementary and middle schools.” These plans of study should focus more on curricular interests—STEAM, math, science, etc. “What are some very specific things that you enjoy doing? See, that’s personalization,” Anderson says. “That looks a little bit different than just having a career fair.”

Topeka middle schoolers are already interning and being exposed to career fields like biochemistry. “We have some creative ways of digitally tracking their individual plans of study,” Anderson explains. That includes giving young students career and college surveys to help point them in the right direction when they get to middle and high school. Then it’s about exposing them to jobs they may not know about. “How would you know you wanted to be a biochemist if you’ve never seen a biochemist?” she asks.

“We really try to outline concepts, standards, and skills. And then we explore what jobs are in each field,” Anderson tells us. “Some jobs you can get within a very short period of time, and so we’ve grown a partnership with our local community colleges.”

As an appointee on the Postsecondary Technical Education Authority, Anderson also helps make decisions about career technical education in Kansas’s public schools and two-year colleges. “If you want students to lead, they have to be prepared with the skills they need to do that,” she says.

Through a partnership with local energy company Evergy, the district is now looking into creating career pathways for jobs in wind energy and science. “That doesn’t take a four-year college degree,” Anderson says. And high school students in the district are already interning at Evergy and being guaranteed jobs right after graduation. The goal is to connect students with their passions, which may mean a job that will earn students a living without years of postsecondary study or debt. “You’re not preparing them for college, you’re preparing them for life,” she tells us. “You’re preparing students to live a life in which their purpose can come alive.”

To do that, educators need to learn what makes their students tick, what energizes them. “That student could be the next scientist, the next mathematician, the next poet, singer, or artist—it’s about finding that part out and creating multiple ways for students to get there,” she explains.

For Topeka Public Schools, proper preparation also comes with high expectations. “We ensure that we teach at the highest levels,” Anderson says. “We ensure mastery is there, and then we offer college credit while you’re in high school so when you leave, you have many options available to you. It’s the path you choose to take; it’s not a matter of the path choosing you.”

Providing their students with as many career options as possible is also about equity. “The best way to continue poverty is to reduce access and exposure—that reduces opportunities, and young people often find themselves in a cycle they can’t see a path out of,” Anderson explains. “We have an opportunity to interrupt that, to disrupt poverty by changing that cycle, by giving opportunities, by exposing young people to many different pathways and careers and letting them know that there are no barriers but your mindset. When you realize that, the whole world opens up for you.”

Being Who You Are

Anderson leads from her heart and mind with a systemic approach to growth and change. When she speaks about her students, she looks you in the eyes as if you’re one of them, and it’s impossible not to feel like you’re being given a lesson by the world’s most sincere teacher—and perhaps you are.

“There are a variety of ways in which leaders can really think about how to engage other people in the work,” she explains. “Ultimately, your purpose becomes a bit of your brand and who you are.”

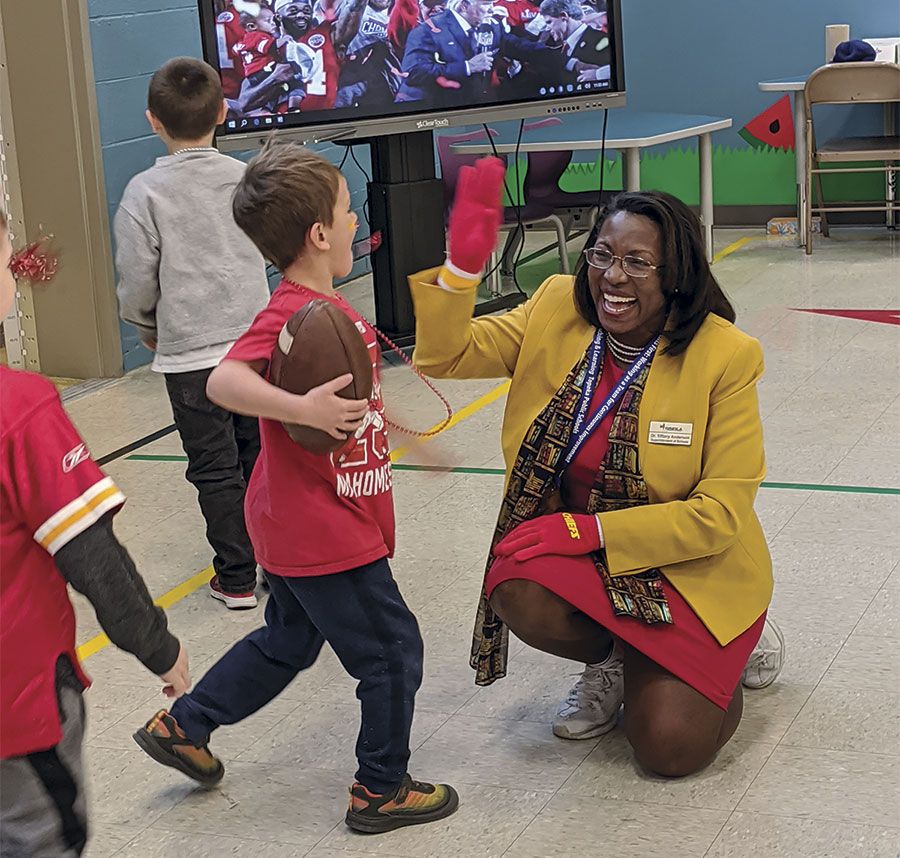

When it comes to branding, Anderson doesn’t seem to have any issues. “No matter what state I’m in, most people know if they see a black lady with a suit and tennis shoes, that’s Dr. Anderson,” she says.

People have long been fascinated with the superintendent’s trademark white tennis shoes. “It’s really kind of funny,” she says. “When I was a teacher, I always wore a suit and tennis shoes to work.” Anderson was raised to dress professionally, “for where you’re going and not for where you are,” as she puts it. “And part of wearing tennis shoes is not only for comfort, but has now become a message—that you must be flexible and ready for anything that comes your way.”

Often, Anderson wears the same pair of white shoes for the duration of each school year. “By the end of that year, they’re holey and torn and dirty,” she says. “You’ve got to be willing to get dirty—and it’s okay, because you know the holes and dirt got there while you were serving boots to the ground.”

Some years ago, Anderson started saving the shoes, writing the date on each pair at the end of the year. “When I was a superintendent in St. Louis, we had the Ferguson riots—and boy, do those shoes look bad!” she says. “Those shoes tell a story.”

The sneakers also let people know that Anderson is who she is. “I don’t need heels and dress-up clothes to show who I am. And I can’t do this work in heels,” she says. “Sitting on the floor, doing crosswalk duty, running down the street to catch a parent, doing a home visit? I need to be ready to meet people where they are and do that humbly.”

Anderson shared this attitude with her late husband, Dr. Stanley Anderson, an award-winning OBGYN and robotic surgeon. Today, she says his memory lives on through her work with children. “He brought them into the world, and I took it from there,” she says. “I had 24 amazing years of marriage to another servant leader.”

In 2016, Anderson was given PricewaterhouseCoopers’ People with Purpose honor, along with an invite to that year’s Academy Awards. “I wasn’t going to go,” she says. “I didn’t need an award to know that what I do is purposeful. Then my husband said, If you go, you get to meet Denzel Washington, so I said, Baby, I’m going! And off to the Oscars I went.” Before her big trip to the red carpet, some of Anderson’s family members convinced her to ditch her white tennis shoes. “I had nice shoes on,” she says, “I had on heels and a ballroom gown, and what do you think people asked me on the red carpet? Where are your tennis shoes?” So she ran back to her hotel room and replaced her heels with her trademark white sneakers. “Now I’m standing there in photos with other people on the red carpet in a ballroom gown with some sparkling white tennis shoes on,” she says, laughing.

Always learning and teaching, Anderson says her experience at the Oscars taught her an important lesson, one she likes to impart on her students. “Be who you are,” she pleads. “Don’t let anyone tell you who you are. Stand on it and know that you are authentically created to be brilliant and great, and that the world is better just because you’re in it.”

Despite her experience and success, Dr. Tiffany Anderson of Topeka speaks with the determination and heart of an educator who’s just getting started. “I was built to serve and to teach and to learn,” she says. “For people who know nothing about my career, just seeing me enter a room full of business suits in my tennis shoes sends a message: Don’t worry about what you’re wearing or what people are thinking about you. Come as you are and be ready to serve—boots, or sneakers, to the ground.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to have a digital copy of the most recent edition of SchoolCEO sent to your inbox.