Bond Campaign Deep Dive: Austin ISD

Listening Equitably · Engaging Minority Families

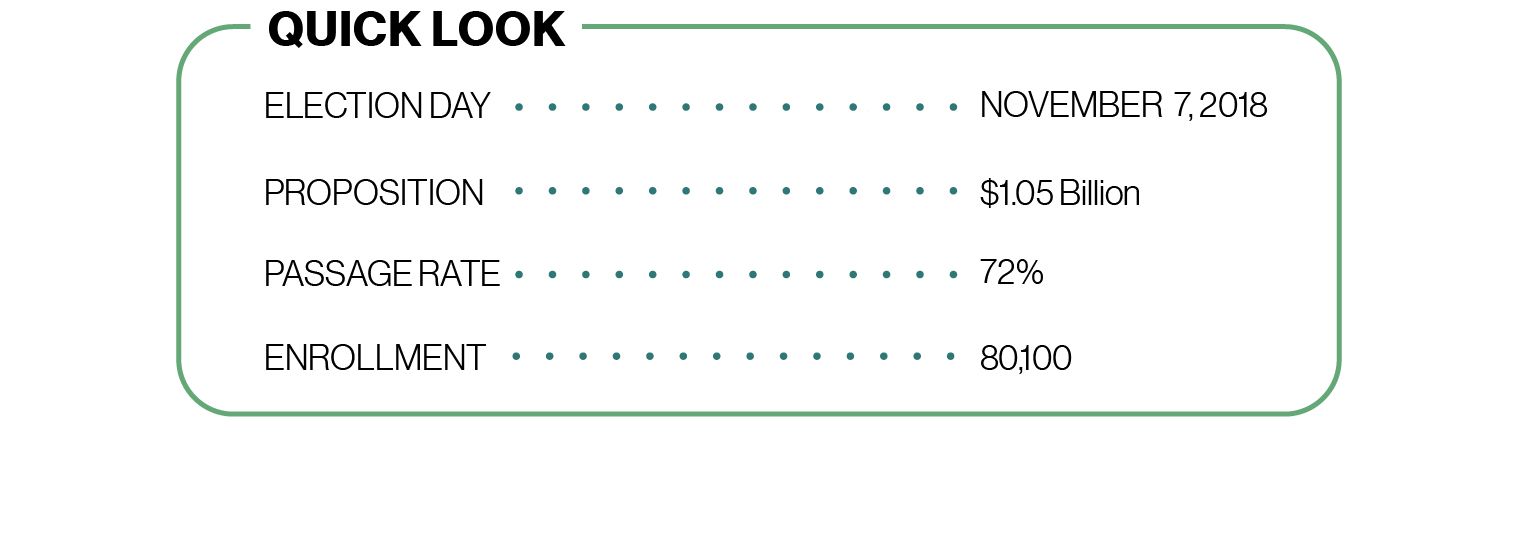

Austin, Texas, is one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States, and its community has a history of supporting school referendums. So when only two of four propositions in Austin Independent School District’s $892.2 million bond referendum passed in 2013, administrators were shaken. Local media speculated the failure might be due to sticker shock, a proposed performing arts center, or even unpopular consolidation proposals.

While the root of the problem is difficult to nail down, there’s no question that reaching such a large, diverse community is a formidable logistical challenge. In total, the district serves over 80,000 students on 129 campuses. More than half of families in Austin ISD—around 52%—are economically disadvantaged, and more than a quarter of students are English learners. Across the district, students speak over 90 languages at home.

Though the district had sought out feedback in the previous campaign, the input they’d received hadn’t necessarily been representative. “Folks that are more affluent had no problem engaging us around questions or answers that they needed,” says Celso Baez III, Assistant Director of Community Engagement and External Communications for Austin ISD. “Some of our communities of color don’t have the luxury or time to dedicate to meetings and aren’t waiting with bated breath for our next tweet or Facebook post,” he explains. “So we had to go to them.”

In the years leading up to the bond, administration has revamped their communications and engagement practices to reach their greater community more equitably. Administrators are paving a path forward to address community hurt and facilitate healing.

Just four years after those two propositions failed, Austin ISD ran and passed a separate bond, this time with only one proposition to the tune of $1.05 billion—the largest funding ask from a government entity in central Texas history. This time, they focused on listening.

Lessons from Austin Independent School District:

Listen equitably.

The way the district had been engaging families, at specific hours and on specific platforms, meant that some voices were being excluded. Even though Austin ISD used fairly typical bond planning processes—conducting an

extensive facilities study of all 129 campuses, creating a bond committee and volunteer group, and holding community workshops—this time, they focused intently on how they were collecting input.

“What we tried to do,” Baez explains, “was look at our engagement practices and really question ourselves: Are we equitably engaging in a way that really reaches our folks who aren’t typically engaged, are historically marginalized, and have the least amount of power?”

Baez considered how to hear the perspective of typically disengaged families. “We tried to design community engagement activities in a way that folks really felt we were doing things with them, and not to them. That was key,” he says. “We could say until we’re blue in the face that we engaged every corner of the district, but if we didn’t make folks feel like they genuinely and authentically engaged with us, like they were heard, then it wouldn’t be effective. Because there’s a lot of residual hurt that has yet to heal based on our city’s segregated past. We know there is rampant distrust in public education across the country, and we knew that any process that would lead toward the bond would move at the speed of trust. We needed to address our school district’s trust deficit. So we didn’t go in there, bull in a china shop, trying to rubber-stamp things.”

Of course, this didn’t mean the district neglected deadlines or goals, but it did mean finding ways to be more present in the process. “We tried to approach the process in a way that humanized the school district and mirrored what we teach our kids everyday around social and emotional learning—to really empathize and listen actively to our communities,” says Baez. “That’s what built the trust in our master plan, the trust to get over 72% of the vote in November.” Once the district developed a plan, the focus transferred to educating the community about the impacts of the 2017 bond.

Communicate with all families.

To get started, Austin ISD leaned on communications structures already in place across the district—principals, parent support specialists, and the community engagement team—especially in the most economically disadvantaged schools and neighborhoods.

“We put together a toolkit that just about anybody could use,” Reyne Telles, Executive Director of Communications and Community Engagement, explains. This toolkit included talking points, a script, and a video—all of which Telles asked his team, along with key administrators and principals, to present twice. “Principals were to present to their PTAs, their staffs, and their advisory councils,” he adds. “So we utilized our district as a large organization to reach as many people as possible.” They also hosted nontraditional engagement hours for parents and community members working two or more jobs or keeping atypical work hours.

For community presentations, the district provided detailed resources, but also let speakers take some ownership of the process. “We did a slide text of what could be said,” Telles explains. They provided different versions of the slides specific to a presenter’s expertise or interests, some as scripts, some as bullet points. “We weren’t pigeonholing a presenter into something that made them feel or seem uncomfortable when they were in front of an audience.”

Of course, proper engagement often meant meeting community members where they already were. “Soccer is a big game in Central and South America,” says Telles, “so we had soccer tournaments to engage adult soccer fans. When players signed up, they were given information on the details of the bond.”

Another night, the team presented bond information at an arcade and bowling alley popular among African American families in the community. By figuring out where the district’s audiences gathered in the city, Telles’s team was able to reach families of color more effectively.

Welcoming the broader Austin ISD community to the table also meant bridging a language gap. “Depending on the audience, we would have two meetings going on simultaneously: one in English, one in Spanish,” Telles says. For Spanish speakers, the district provided headsets to listen to an interpreter. “It was the exact reverse of that when the majority population spoke Spanish; then English speakers got headsets,” he adds.

The district also added bond-specific episodes to their biweekly television program, Breaking Down the Barriers. This show provides information for all families, especially families of color, in regards to programs and initiatives available in the community. In these special episodes, they broke down the bond in great detail, making the entire project more accessible.

Because the district had engaged the community up front, they were prepared to face any opposition. When a PAC formed against the bond, the district simply doubled down on the truth. “They felt like the slogan itself, without a tax rate increase, was disingenuous,” saysTelles. “We were very transparent that the tax rate would remain flat. Families could still see an increase in their taxes based on the rise of home values.”

The district also predicted certain questions and concerns, and provided paper and digital copies of FAQs. “We weren’t afraid to put it out there whenever we heard there was criticism or a communication question,” Telles says. Generally, the district maintained a positive message throughout the campaign. “When you look at our communications plan, it says not to spend a lot of energy on the people whose minds you won’t change anyway,” Telles says. “It’s really getting the support of people you know are cheerleaders for the district and our schools.”

In November of 2017, 72% of Austin voters approved the measure. If you ask Telles about the district’s success, he’ll give credit to having a master plan and to listening to the community. “At the end,” he says, “it all comes down to trust in the organization.”

The listening process didn’t stop after the vote. Visit Austin ISD’s website and you’ll see opportunities to submit comments and ideas, or to attend workshops. The district also employs Historically Underutilized Businesses to fulfill bond-funded construction, showing a commitment to minority- and women-owned businesses.

To maintain community trust, Austin ISD keeps voters well-informed. Not only does the district send out quarterly newsletters related to the bond, but they also maintain a webpage for each construction project, including biweekly drone videos to show progress. The district is also sure to invite members of the voting community, even those without kids in school, to celebrations like groundbreakings or ribbon cuttings. Again, for Austin ISD, it’s all about engagement, giving the entire community ownership of the district’s schools.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!