Our teacher satisfaction survey spanned generations.

In the largest study of its kind, we asked educators what they look for in a job and how schools can improve their teacher recruitment.

This article is even better when paired with the companion discussion guide.

In Spring 2019, against the backdrop of an accelerating teacher shortage, we published “What Do Millennial Teachers Want?” In the largest study of its kind, we surveyed over 1,000 millennial teachers from across the country to explore questions like, What matters most when millennial teachers are deciding where to work? How do they find out about their jobs? How deeply does an educator explore a school’s online presence when applying?

Just a couple of months later, U.S. Census data confirmed that millennials had officially surpassed baby boomers as the largest living—and working—adult generation. At the time, a growing body of educational stakeholders had reached consensus that the country’s 56 million working millennials were the solution to teacher shortages. After all, the overwhelming majority of educators traditionally entered the classroom before age 40—and in 2019, the oldest millennials were turning 38. But the problem was more complex than a numbers game. By the start of the 2019-20 school year, the Learning Policy Institute reported that the demand for teachers had exceeded supply by more than 100,000 positions—confirming the presence of a significant break in the college-to-classroom pipeline.

Today—only four years later—most of the rules of old no longer apply. Gone are the days when teachers entered the classroom at 22 and stayed until retirement. Now, teachers leave the classroom much earlier. Research from the National Education Association (NEA) suggests that nearly 50% of new educators leave the profession within five years.

Of course, shortages have been compounded by the pandemic. But even if we exclude COVID, a lack of flexibility, expanding workloads, and increasingly hostile perceptions of education are deterring young people from entering the field in the first place. As a result, public schools are getting creative with their recruitment efforts.

That’s why we decided once again to explore the same ideas we researched in 2019—only this time, we conducted a teacher satisfaction survey across five generations, from ages 20 to 80. But while we’ve expanded the parameters of our study, our goals are much the same as they were four years ago. We want to know what teachers of all ages look for in a job, how they learn about open positions, and what you can do to attract—and retain—the best educators.

Who took our teacher satisfaction survey?

Between October and December 2022, we surveyed over 1,000 teachers from more than 300 randomly selected school districts. Our sample includes educators from all 50 states and all working age groups, and shares demographic consistencies with other nationally representative samples collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Gender: Approximately 76% of our respondents were women; 24% were men. Less than half of 1% were nonbinary (Figure 1).

Race and Ethnicity: Teachers were asked to indicate which ethnic and racial groups they identified with. These options weren’t mutually exclusive—respondents could select as many options as they needed to accurately identify themselves. More than 9% identified with two or more ethnicities.

Age: Consistent with NCES’s measures, the average respondent in our sample was about 43 years old and has been teaching for about 14 years. In addition, half of all teachers in our sample were 43 or younger. This isn’t a surprise considering that millennials and Gen Xers made up approximately 37% and 42% of our sample, respectively. About 14% of our sample consisted of baby boomers, and Gen Z followed at almost 7% (Figure 2).

Education: About 36% of respondents’ highest level of education was a bachelor’s degree. Over half of our sample (54%) had master’s degrees.

District Size: 27% of our respondents said they worked in an urban district; 29% in a rural district; and 43% in a suburban district (Figure 3).

We also found that age and gender are pretty evenly distributed across districts. In other words, for the time being, there’s no evidence suggesting that certain generations or genders gravitate toward certain districts, or that specific members of either category are motivated to pursue work in rural, suburban, or urban districts for any of the reasons we captured here. This means that in any given district, we could anticipate about 90% of educators to be between ages 20 and 60, that about half of educators would be 43 or younger, and that the majority of teachers would be women.

Are teachers considering new opportunities?

In their 2022 survey report, the NEA concludes that job satisfaction for teachers is at an all-time low. Teachers across the board are experiencing unprecedented levels of strain in their classrooms, increasing workloads without increasing salaries, and widespread burnout—all compounded by shortages and growing public criticism. Our analysis, however, indicates that the situation may not be quite so dire.

We asked respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: “I am happy in my current position.” Surprisingly, only about one in five respondents expressed any level of disagreement. In fact, only 5% of our sample strongly disagreed with the statement, as compared to the 19% of respondents who strongly agreed. Overall, nearly 65% said that they were at least somewhat happy in their current jobs (Figure 4).

But how much does happiness impact teachers’ job hunting behaviors? When we asked teachers to indicate whether they’d browsed for other job opportunities within the past year—even if they had no intention of actually applying—about 65% of our sample indicated that they had (Figure 5). Unsurprisingly, our analysis revealed that unhappy teachers were more likely to report having browsed other job opportunities than happy teachers.

A teacher’s happiness also appears to impact their likelihood of actually applying to the jobs they’re exploring. When asked, nearly a quarter of our sample—about 23%—said they had applied to at least one other position since starting in their current roles (Figure 6). However, we didn’t find evidence that happiness—or unhappiness—is the strongest predictor of whether a teacher will explore opportunities elsewhere or not.

In fact, happiness only accounted for a small amount of the variation in responses revolving around job browsing. These findings align with a broader trend appearing in labor markets across a variety of industries that BBC Worklife refers to as “the Great Flirtation”: “a constantly wandering eye to other openings, regardless of how long a worker has been in a role, and how content they are in their current job.”

Are teachers looking to leave education?

We asked respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: “I would leave the field of education if given the opportunity.” Their responses revealed a nearly even split down the middle. Forty-three percent of educators appeared to disagree with the statement to some level, while 40% agreed (Figure 7).

But are teachers actively trying to leave the classroom? The answer is mixed. Of respondents who indicated that they had applied elsewhere since starting in their current positions, 80% said they’d applied to other jobs in education. It would appear that even those who are trying to leave their current districts aren’t necessarily trying to leave the field—though they aren’t completely opposed to it, either. Our data indicates a relationship between how frequently a teacher hunts for other jobs and their willingness or desire to leave education. In other words, the more frequently an educator explores other career opportunities, the more likely they are to be willing to leave the classroom altogether.

Predictably, we also found a statistically significant relationship between an educator’s happiness in their position and their willingness to leave the classroom. Our analysis suggests that happy teachers are more likely than unhappy teachers to plan on staying in their current positions indefinitely or until retirement. In other words, unhappy educators have significantly more interest in leaving their current positions—and the teaching profession—than their happier counterparts.

For school leaders, the takeaways here are fairly simple: Making sure your teachers are happy might not keep them from looking at other jobs, but it could keep them from actually leaving your district—or even education in general. But how can you keep your teachers happy? What do educators want?

What are teachers looking for in a job?

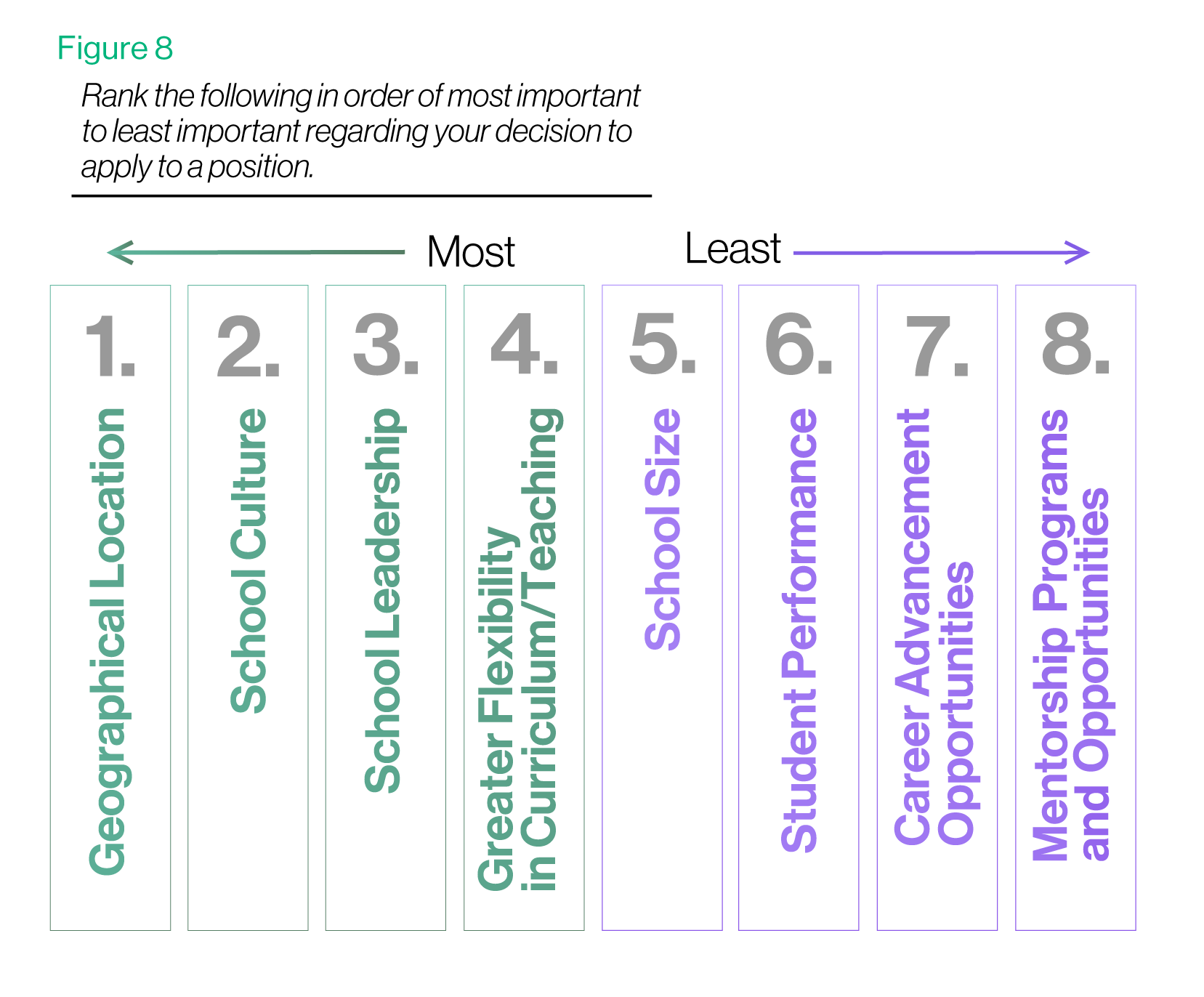

We asked respondents to rank the following factors in order from most important to least important regarding their decision to apply to a position:

- School Culture

- Mentorship Programs and Opportunities

- School Size

- Geographical Location

- School Leadership

- Greater Flexibility in Curriculum/Teaching

- Student Performance

- Career Advancement Opportunities

Geographical location ranked highest among these factors, followed by school culture and leadership. At the lower end of rankings, our respondents indicated that when it comes to making career decisions, student performance, career advancement opportunities, and mentorship programs and opportunities were overall less important than other dimensions. This doesn’t mean that student performance and access to mentors aren’t important to educators, though—other characteristics simply take priority (Figure 8).

Interestingly enough, location, culture, and leadership were also the top three considerations identified by respondents in “What Do Millennial Teachers Want?” nearly four years ago. Let’s dig a bit more into each of these dimensions.

Geographical Location

Respondents indicated that the geographical location of an opportunity weighs heavier than any of our other seven dimensions when it comes to making decisions about where to work. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that teachers are itching to move to pursue new opportunities; in fact, the opposite may be true.

We asked respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: “I am willing to move or considering moving to a new area to pursue another career in either teaching or a non-education related field.” About 30% of teachers indicated that they would be willing to move to a new area to pursue another opportunity, while almost 60% of educators indicated little to no interest in moving. It may be that teachers are emphasizing location in their job searches because they don’t want to move and are therefore mainly considering opportunities in their current areas.

However, if nearly a third of teachers are willing to relocate, you can’t discount the possibility of teachers moving to your district from somewhere else—and weighing the benefits of your location in their decisions. For example, Gen Zers indicated a significantly greater willingness to move for a new career opportunity than Gen Xers and baby boomers. If you want to attract teachers from outside your immediate community, it’s a good idea to market the benefits not just of your school district, but of its surrounding area. (For more about marketing your location, click here.)

School Culture

Our respondents ranked school culture as the second-most important factor in their career decisions. This priority was also reflected by the answers to the open response portion of our teacher satisfaction survey. When we asked teachers what advice they’d give to school leaders about marketing a district and its open positions to prospective teachers, “culture” was the fourth-most common word in their responses (after “teacher,” “school,” and “district”).

Looking more closely at these open-ended responses can help us better understand what kind of school culture teachers are looking for. For example, many related the idea of culture to strong relationships between colleagues. “Play up your school culture,” one respondent advised. “If you honestly believe there’s a positive school culture and colleagues have strong relationships, talk about it. It’s a huge pull—teaching is a profession that is extremely dependent on working relationships between adults.”

A few teachers even offered advice for how to build that kind of relational culture. “Highlight what you have to offer teachers in terms of social support [and] opportunities,” wrote one respondent. “This ... can be anything from having little traditions like having monthly birthday lunches to having a Christmas party to playing a game with prizes before each staff meeting. In my experience, a teacher should feel like they can fit in easily and get to know their colleagues. The better they fit into the school social puzzle, the more likely they are to find common ground and be invested in staying for more than the pay and benefits. We need to have connections with others for the best teamwork and communication.”

Support, respect, and appreciation were also common themes. One respondent recommended building “a positive school culture with supportive administration who value educators as professionals”; another wanted “a supportive, engaging culture that values staff and student input.”

School Leadership

Third—but not far behind location and culture—comes school leadership. But what are teachers looking for in their school leaders? Once again, we turn to our open responses for more context.

Here, the idea of support emerges again as a major theme. “Teachers need support from leaders,” wrote one respondent. “If a teacher knows [they are] supported and backed, that goes a long way in feeling happy in [their] job.” Another emphasized the distinction between genuine support and micromanagement: “Good teachers want to work for districts whose administrators have their backs and aren’t just looking over their shoulders, who can help them grow without cutting them down to size.”

Others stressed the importance of authenticity in leadership. “Give true statements about your leadership and school climate beliefs, and give examples of actions taken by your leadership and staff that support your beliefs,” wrote one respondent. In other words, put your money where your mouth is. Other respondents also said they were impressed by leaders who stick to their principles. “Evidence of ‘backbone’ in the school leadership is one of the big things that I look for,” wrote one teacher.

And although our sample ranked culture as a more important consideration than school leadership, we don’t have to tell you that leadership has a massive impact on culture. Teachers recognize this, too. “If we are giving advice to DISTRICT leaders, like superintendents, I would say that you and your staff at the upper management level set the tone for the whole district,” one respondent wrote. As another teacher put it, “School leadership can make or break your experience.” It’s critical that you as a school leader recognize your responsibility to cultivate the kind of supportive, relational culture that will attract and retain quality teachers.

What about salary and benefits?

Of course, no conversation about what teachers want would be complete without addressing the elephant in the room—compensation. We asked respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: “My decision to work in my current district was primarily shaped by salary and benefits.” We were somewhat surprised to find that the answers were split pretty evenly; 42% disagreed at least to some degree, while 39% agreed at some level. About 19% were neutral (Figure 9).

Compensation also emerged as a major theme in our sample’s open responses. Among respondents to our teacher satisfaction survey, general consensus appears to be that while nobody expects to get rich teaching, pay is important. “No one will say that they teach for the money, but if the salary was marketed, it might attract more prospective teachers,” wrote one respondent.

Salary also seems to play a part in a teacher’s cultural experience of the district, particularly whether or not they feel appreciated. “Teachers want to work in a district where they feel valued and respected—by the admin, community, and students ... [and] we want to be compensated accordingly,” wrote one educator. “We are tired of doing things ‘out of the goodness of our hearts.’ That doesn’t pay the bills or support our families.” Others, however, claimed that other factors matter just as much as, if not more than, salary. “It’s not the money that makes teachers teach—it’s feeling supported,” wrote one teacher.

Our respondents also indicated a desire for transparency around salary on the front end. “Be upfront about how much a position will pay,” one respondent wrote. “It’s ridiculous to post a job and not include a salary.” Others expressed a desire to see pay scales or to understand how the evaluation process might affect their salaries over time.

All told, it seems clear that while salary is important, money alone isn’t enough to significantly move the needle on teacher recruitment. One overarching theme transcends all the narratives we identified in our analysis: the need for balance. Many of our respondents argued for the necessity of competitive pay while also acknowledging that other factors matter just as much. “Money is great and an added benefit,” wrote one respondent, “but I would stay in a building if the culture was amazing and I was appreciated.” In short, raising pay without improving your culture may not do much to help your teacher recruitment—or your retention.

How do teachers learn about open positions?

Great culture, strong leadership, and competitive salaries won’t do much for your teacher recruitment unless prospective hires actually hear about them. So where are today’s educators learning about jobs—and how can you use those platforms to your advantage?

Does social media matter?

When it comes to social media, about 70% of our respondents indicated that they use Facebook, 55% use YouTube, and 49% use Instagram. Only 21% of teachers in our sample indicated that they use Twitter, while about 27% reported using TikTok. And between generations, the only significant difference in usage was on Instagram. Unsurprisingly, Gen Z educators are more likely to use the platform than Gen X or baby boomer educators.

But even though 97% of our respondents reported using at least one platform, our sample appears largely apathetic toward school social media. For example, almost one-third of our sample strongly disagreed with the statement, “I look at school social media posts on platforms like Facebook and Instagram,” while only 10% of respondents strongly agreed with the statement (Figure 10). Only a minuscule 1.4% of our sample reported learning about their jobs through social media.

This doesn’t mean that you should completely ignore social media in your teacher recruitment strategies—but these findings do suggest that schools should be focusing the majority of their recruitment efforts elsewhere. As with any kind of marketing, you want to meet your prospective recruits where they are—and for now, that doesn’t seem to be on social media.

What about school websites?

We asked respondents, “Before applying to the district you currently work in, did you look at the school’s or district’s website(s)?” Over 70% indicated that they had done so (Figure 11). Furthermore, 38% reported first learning about their positions through school or district websites, and 64% indicated looking online for information before accepting a job offer.

But here’s where it gets interesting: When we asked respondents to agree or disagree with the statement, “My school’s online presence attracted me to my current position,” 57% of our sample said they strongly disagreed. Less than 10% agreed in any capacity. In fact, almost 84% of our sample indicated that their school’s online presence did not attract them to the role at all (Figure 12).

These findings present an interesting dilemma. While prospective teachers don’t seem to be engaging with school social media much, an overwhelming majority are visiting school websites—but those websites aren’t necessarily attracting applicants. So what can school leaders do to make their websites more successful teacher recruitment tools?

Make sure your website is mobile friendly. When asked, more than three-quarters of our respondents (76%) reported using their phones to research the jobs they apply for. What’s more, your largest talent pool—millennials and Gen Zers—are even more likely to search for jobs on smartphones than other generations. If your website doesn’t work well on mobile devices, you’re creating barriers for a substantial proportion of your potential recruits.

Keep your site updated. “Make sure your websites are ALWAYS and COMPLETELY up to date,” one teacher advised. “Anything less is a turnoff to potential employees.”

Make information easy to find. The more relevant information potential applicants can find directly from your homepage, the better. “Make a website that is easy to navigate and looks clean and modern,” one respondent wrote. “Have links to any social media sites on the homepage. Have a tab for open positions.”

Make it look good. According to research from the journal Behavior & Information Technology, it takes about 50 milliseconds—one-twentieth of a second—for a user to form an opinion about a website. A poorly designed website can ruin a candidate’s first impression of your district before they even get any information. In the words of one respondent, “have a website that doesn’t look like it came straight out of the ‘90s.”

Highlight your culture on a careers page. Your careers page should include more than just job descriptions; it should also be selling potential applicants on your district and its culture. “Post information about awards and nominations current staff have won; post testimonial videos from staff and students about how great your district is; post a video showing your upcoming graduates and how much scholarship money they have been offered; show NHS kids doing all their volunteer work,” one respondent suggested. “Potential employees want to see a thriving district with high-caliber students who are well-rounded citizens in their community.”

How important is word-of-mouth for teacher recruitment?

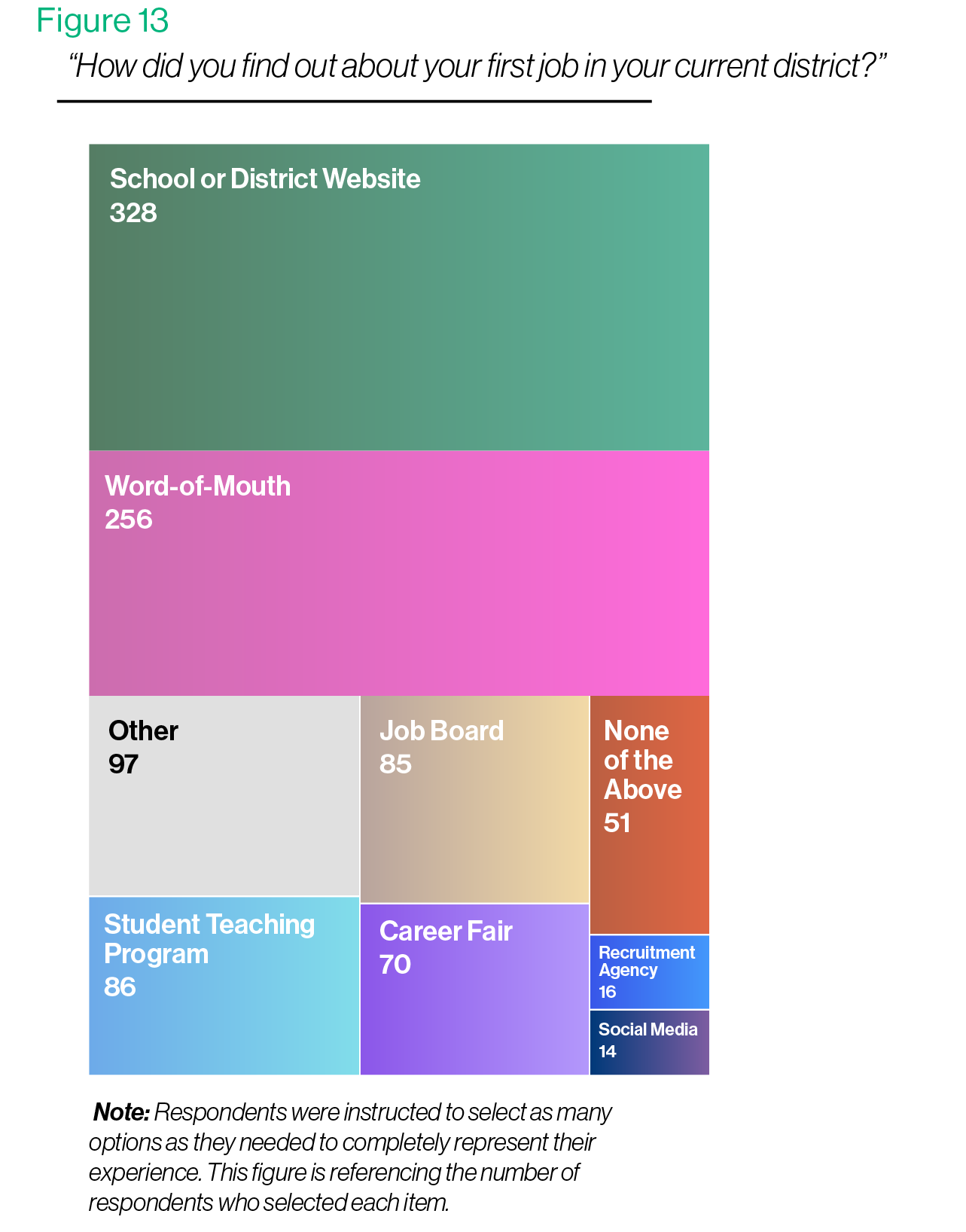

More than a quarter of our sample (26%) reported learning about their first jobs in their current districts through word-of-mouth (Figure 13). That’s more than any other avenue besides school or district websites. It’s clear that even in the so-called digital age, word-of-mouth marketing matters. So how do you make it work to your advantage?

The answer is fairly simple: Build a positive culture, and your employees will talk about it. Teachers reflected this idea in their open responses. “Create a supportive working environment that teachers brag about,” said one respondent. Another agreed: “Produce a culture where current employees will recruit friends based on how happy they are.”

That said, word-of-mouth can deter applicants from interacting with your district just as easily as it can attract them. If your culture and leadership are lacking, prospective teachers in your area will hear about it. “Teachers know how well other districts value their teachers, and while we know that no school is perfect, the perception of teacher value is important,” wrote one respondent. “When 20% of a staff is leaving, it’s not because other schools were marketing themselves better—it’s because somewhere along the way there was [or] is a failure of leadership. The best marketing is happy employees. Teachers talk; treat them well.”

If you’re like most school leaders, you’re probably thinking about the education labor crisis around the clock. You wake up to read alarming reports about the drop in enrollment in teacher preparation programs, and you fall asleep after reviewing hiring goals for next year. The challenge that most school leaders are facing is immersive and overwhelming. All of this can contribute to a general feeling of powerlessness, especially against the backdrop of other crises facing K-12 education.

But our findings suggest a more hopeful narrative. Teachers are happier in their jobs than you might expect, and they’re not all set on leaving the profession—or even their current positions. That means that when it comes to teacher recruitment, you actually do have a great deal of power. By understanding what teachers are looking for in a job—namely, strong culture and leadership—you can make sure your district is constantly improving in these areas. And by knowing where and how teachers are finding jobs, you can adjust the tactical strategies of your teacher recruitment process to net as many applicants as possible.

There’s no doubt that much of what makes teacher recruitment difficult is outside your control—but take charge of the areas you can. Every district is operating under the constraints of a difficult labor market, so any advantage you can create will give you a better chance of attracting top talent. By giving teachers what they want, you can move closer to what you want: a district full of happy and dedicated educators.

Originally published as "What Teachers Want" in the Winter 2023 edition of SchoolCEO Magazine.

Brittany Keil is a writer and researcher with SchoolCEO and can be reached at brittany@schoolceo.com.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!