Common Ground

In our latest research, we examine the essential collaboration among superintendents, comms directors and technology officers.

This article is even better when paired with our companion discussion guide.

In the past decade, online school communications have become a necessary cross-functional duty of every school district in the U.S. As districts deploy sophisticated communication campaigns that include robust multipurpose websites, apps and two-way communication tools, central office teams have had to work together to ensure functionality, safety and accessibility. Within these teams, three major positions stand out: the school superintendent, the leading technology officer and the leading communications officer.

While the duties associated with these roles vary by district location and size, each of these major players brings their own perspective to school communications. Superintendents typically view school communication in terms of how it relates to their district’s overall health. Chief communications officers typically think about what types of communication are coming from which layers of the district—and what strategy ties them all together. Tech directors, finally, often conceptualize communication tools like school websites and apps as part of a broader technology network, and are most concerned about aspects like functionality and security.

But given these disparate and sometimes conflicting priorities, how can these three leaders work in sync to create communications strategies that satisfy all their needs? That’s exactly what we hope to uncover with this report. First, we synthesize existing research on each of these roles. Then, we share insights from three original case studies of districts across the country, to better understand the perspectives of each position and show what effective collaboration among these roles can look like.

About This Study

We set out to understand the complex working relationship between superintendents, school comms and tech pros with three guiding questions:

What is the demographic makeup of each role, and how do they differ from one another?

What are the priorities of each role?

What best practices can we learn from districts where these three leaders work together successfully?

Data and insights for this study come primarily from three sources, all of which are longstanding authorities in their respective fields: AASA, The School Superintendents Association; the National School Public Relations Association (NSPRA); and the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN).

To leverage these organizations’ expertise, we conducted a thorough study of their most up-to-date literature, as well as interviews with scholars Dr. Christopher Tienken and Paula Maylahn. Tienken, an associate professor of leadership, management and policy at Seton Hall University, serves as AASA’s research professor in residence and edits the organization’s Decennial Study of the American Superintendent. Maylahn, an independent consultant with more than 30 years in education, authors CoSN’s annual State of EdTech District Leadership report. We also cite findings from our 2024 research study produced in partnership with NSPRA, “A Seat at the Table: Research on the Relationship Between Superintendents and School Communicators.”

While many communications and tech officers work on teams of one, others (often in larger districts) lead wider teams. In general, throughout this study, we are considering the highest-ranking person in each department.

WHO ARE AMERICA'S SCHOOL LEADERS?

AGE

RACE

GENDER

YEARS AS:

Who’s Who in School Communication

First, let’s investigate who occupies these crucial roles in school communications. Although they may share spaces in the central office, the people who fill the roles of school communicator, tech director and superintendent often have wildly different backgrounds and priorities—which can sometimes put them at loggerheads. But when things go well, these differences in perspective can make a school communication strategy much stronger.

The Superintendent

Although the role has seen some diversification in the past few decades, the superintendency remains overwhelmingly white and male (Figures 2 and 3). In fact, The Superintendent Lab, a research group headed by Dr. Rachel White at the University of Texas, humorously underscored the homogenous nature of the role—finding that one in five superintendents is named “Michael, John, David, Brian, Chris, James, Jeff, Robert, Matthew, or Mark.”

Superintendent turnover has increased somewhat over the past decade—and it has become less common for superintendents to stay in one district for the majority of their careers. Additionally, according to AASA Research Professor in Residence Dr. Christopher Tienken, superintendents are entering the role earlier in their careers. “They once typically spent a lot more time as principals or in other administrative roles, but that is no longer the case,” he explains. Close to half of superintendents entered the role five years ago or less (Figure 4).

Superintendents also have, by far, the most visible and expansive role in the school district. In AASA’s most recent Decennial Study, published in 2020, they are referred to as the “human hub” of the district. They must alternately serve as CEO, politician, chief budget officer and chief culture officer—and that’s just scratching the surface. From hiring to bus routes, just about every decision involves the superintendent.

The Chief Technology Officer (CTO)

In some ways, CTOs are similar to superintendents. The majority of both groups are white and male (Figures 2 and 3), although there are more women in the K-12 tech space than in similar roles outside of school systems.

Out of all three administrators, the role of chief technology officer has likely changed the most in the past few decades. Twenty years ago, the work of CTOs centered more around technological infrastructure—such as maintaining phone systems, classroom projectors and desktop computers. But given the rapid expansion of technology use in schools, tech directors have had to quickly adapt to keep up.

“School districts initially relied on their IT departments to manage the wires and switches,” explains Paula Maylahn, author of CoSN’s annual State of EdTech District Leadership report. “Now, everything involves them.” And a surprising number of CTOs have been in their careers a long time—meaning that they’ve witnessed this shift firsthand. More than half are over the age of 50 (Figure 1), and almost 70% report being tech leaders for over a decade (Figure 4).

Maylahn says that five years ago, many CTOs were working to solve for the breakneck switch to online learning—ensuring internet connectivity for stakeholders, choosing products to facilitate instruction and quickly implementing one-to-one device policies. Now, they’re building policies and procedures to respond to the rapid spread of artificial intelligence (AI) while also protecting their districts against increasing cybersecurity threats. According to recent research by the nonprofit Center for Internet Security, 82% of schools reported experiencing a cyber incident between July 2023 and December 2024. Needless to say, the constant shifts in K-12 tech don’t appear to be stabilizing anytime soon.

The Chief Communications Officer (CCO)

While some larger school districts have employed comms professionals for decades, the pandemic’s forced emphasis on school communications prompted many more to add the role to their teams. And thanks to the progression of the school choice movement—from the emergence of charter schools two decades ago to the swift state adoption of voucher programs in the past few years—public schools can no longer afford to deprioritize communications and marketing.

As a group, school communications professionals are strikingly different from the other two roles in this study. While (like their counterparts) the majority of them are white (Figure 2), most school communicators are women (Figure 3). What’s more, as we found in our 2024 research “A Seat at the Table,” many of them come from careers outside of school systems. Nearly half of school comms pros come from public relations or marketing backgrounds, and a quarter started their careers as journalists. This gives many comms professionals a perspective that is often missing in district cabinet meetings. Unlike their colleagues with backgrounds in education, they are less likely to be familiar with so-called “eduspeak” and more likely to consider how messaging will sound to families and community members.

The field itself is also changing. School communicators now juggle multiple responsibilities—from social media to website management to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. And as we found in our research, many school comms professionals feel dissatisfied with how they spend their time, as urgent tasks like crisis communications often take precedence over long-term planning and strategy.

|

FIGURE 5:

PRIORITIES BY ROLE |

||

|

SUPERINTENDENTS

Finance

Personnel Management

Conflict Management

Superintendent-Board Relations

School-Community Relations

Facility Planning/Management

Law/Legal Issues

School Reform/Improvement

Curriculum/Instructional Issues

School Safety/Crisis Management

Policy Development/Management

Student Discipline

Education Equity/Diversity

|

COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTORS

Crisis Communications

External Communications

Social Media

Community Relations/Public Engagement

Media Relations

Website Management

Internal Communications

Strategic Communication Planning

Writing/Editing

Marketing

|

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORS

Cybersecurity

Data Privacy & Security

Network Infrastructure

Determining AI Strategy

IT Crisis Preparedness

Cost-Effective/Smart Budgeting

Parent-School Communication

Broadband & Network Capacity

|

Complementary, Not Conflicting

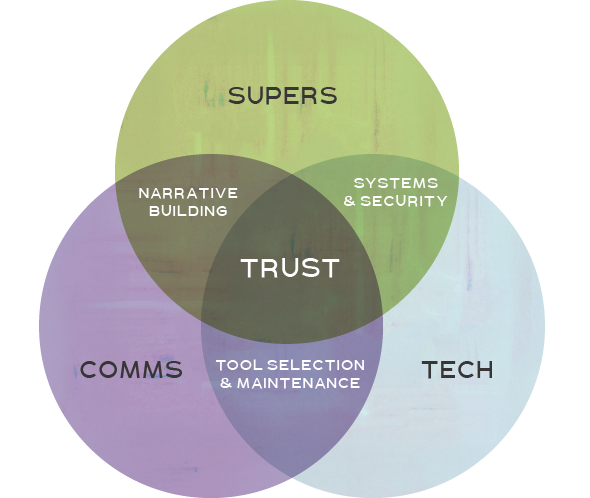

Each of these three personas brings their own perspective and priorities to the task of school communications. But even if they don’t seem like it at first, these priorities often overlap and complement each other—and recognizing these overlaps will make collaboration a lot easier.

In the studies we referenced, AASA, NSPRA and CoSN each supplied a list of potential priorities or tasks, and asked their respective respondents to rank them. In Figure 5, we compare those ranked lists side-by-side. As you’ll see, while each administrator has their own focus, their top priorities share a common thread: building a relationship of trust with the broader community. These priorities are especially important given that Americans’ trust in public schools is at a 24-year low, per Gallup’s 2025 Mood of the Nation survey.

In recent years, superintendents have become increasingly likely to be embroiled in political conflicts with their school communities. As discussions around school choice—and therefore school finance—have become more heated in the past few years, these stressors have also topped the list of superintendents’ concerns and priorities. For Tienken, this pressure has been compounded by the amount of misinformation that superintendents must now contend with, both on social media and elsewhere. “Superintendents spend much of their time responding to misinformation. Some of that they can do proactively, but there’s plenty of reactive work, too,” Tienken tells SchoolCEO.

Comms professionals also feel this pressure to build and maintain community trust. Crisis communications, external communications and social media management top the list of what school communicators spend their time on—even as areas like internal communications and long-term strategic planning are forced to the bottom of their to-do lists.

One might assume that, since they are less outward-facing than superintendents and CCOs, technology officers would be somewhat removed from issues around district-family communications and combating misinformation. But this isn’t the case. While many of CTOs’ top priorities reflect behind-the-scenes work such as infrastructure and interoperability, providing a seamless, safe experience for students and families is a tech director’s north star.

This is especially true as cybersecurity has risen as a focus—an issue that can easily impact how much a community trusts their district. Maylahn, who has spent the last decade surveying CTOs on their priorities, has seen parent-teacher communication continually rise as a tech priority. “Ten years ago, parental communication wasn’t even on our radar as something CTOs were dealing with,” Maylahn says. “Now, that’s absolutely not the case.”

Notice that for all three roles, parent communication or school-community relations are listed as either priorities or—in the case of superintendents—issues taking significant time. Both of these priorities share a common theme: relationships with the community. Given their other priorities though, this shared focus shows up differently for each role.

Same Goal, Different Lens

Despite their different perspectives, each of these three leaders operates with the same goal in mind: to ensure that their district gains and maintains its community’s trust. However, they each see that goal through their own unique lens. When each of these lenses are adequately understood and included in decision-making, the result is increased faith in the district.

Consider the following hypothetical: In auditing parent-teacher communication practices across their district, a central office team finds that teachers are using a variety of tools to communicate with families. From the communications officer’s perspective, this lack of cohesion creates a less-than-ideal experience. Families—especially those with multiple children in the district—may be unsure where to look for important information, negatively impacting their trust in the district. The technology officer might have concerns related to trust as well, but from a slightly different angle. For them, building trust means keeping student data safe—and the more communication apps teachers are utilizing, the harder it becomes to ensure each one meets the district’s security standards.

On their own, the superintendent might not have considered either of these perspectives—but ideally, they have regular time set aside on their calendar to meet with these other two leaders. Both tech and comms have time to bring up their concerns, and together the team decides to choose a standard two-way communication tool for all the schools in their district. But what tool to pick? Again, each person in the room brings their own considerations to the table. For the comms officer, the key factor is effective communication itself; for the tech officer, it’s data security. The superintendent, meanwhile, has to consider the district’s budget as well as staff buy-in. Adopting a tool that’s too expensive could damage trust with the community, while adopting one that teachers hate will damage internal trust.

No administrator alone can see this problem from every angle at once, but each viewpoint is critical to finding a solution that effectively meets their shared goal. Ignore or exclude any one of these perspectives, and the district runs the risk of losing trust—the crucial currency on which all schools run.

Finding Common Ground: How to Make This Work

So how can your team work together to build and reinforce your community’s trust in your district? We’ve got five steps to get you started.

Everyone needs a seat at the table.

If you read SchoolCEO’s 2024 collaborative report with NSPRA, you won’t be shocked to learn that communicators can’t do their best work if they are excluded from the decision-making table. But in speaking to Maylahn, we were surprised to learn that this challenge isn’t unique to communications—it’s felt acutely by tech departments as well.

“Plenty of tech directors have been with their districts long enough to see multiple rounds of administration,” Maylahn explains. As a result, they’re ideally positioned to play a role both in decision-making and in helping stakeholders understand the why behind the decisions. After all, they’ve invested more time than anyone else in ensuring that tools work with others used throughout the district—all while satisfying privacy and security needs.

Having access to decision-making spaces also gives each leader the chance to share how their perspective is relevant to the decision at hand. After all, no one likes to find out a decision relevant to their expertise has been made without them, especially if this changes their workload or other aspects of their job. And, of course, including more viewpoints will result in better decisions in the end.

Interdepartmental communication should be frequent, fluid and grounded in respect.

Each of the researchers we spoke to stressed the importance of frequent, high-level communication between superintendents, communications directors and technology leaders—as well as the importance of understanding one another’s perspectives. “Those three people need to get in a room and do some soul-searching,” Tienken advises. “List your strengths and weaknesses as communicators and as problem-solvers. Communication and problem-solving go hand-in-hand, and while each position has complementary strengths, they can’t know where to go until they know each other.”

As you can see in our case studies, successful collaboration between comms, tech and superintendents hinges upon frequent and fluid communication. But you can’t communicate effectively without intentionally setting aside time to do so. “Nothing can happen without functional relationships, and that means meeting more than once or twice a year,” Maylahn says. “It’s important to have standing meetings with agenda items, even if tech and comms are already part of a superintendent’s cabinet.”

So build time into your schedules to discuss shared projects at regular intervals, even if nothing is changing. The more frequently you all get together, the stronger your relationships will be—and the more natural your collaboration and communication will become.

Shared professional development is hard to get, but invaluable.

Both Maylahn and Tienken discussed the need for frequent, team-based professional development, especially given the fast-paced change in the fields of technology and communication. “The problem with having your job change every few years is that you almost always need professional development around emerging technologies,” Maylahn explains. Unfortunately, opportunities for this kind of PD are few and far between, and difficult to schedule even when offered. Furthermore, when budgets are lean, professional development spending is often one of the first areas cut.

If team-based professional development isn’t possible for your district right now, try having each leader attend professional development outside their field of expertise. For instance, a communications director could attend sessions with their tech director at CoSN’s annual conference, or a tech director could work through NSPRA’s rubrics of practice. Giving each member of the team exposure to each other’s industries—including trends and best practices—can develop both mutual understanding and stronger rapport.

Strong data makes for stronger decisions.

In addition to their subjective viewpoints, each departmental leader has access to unique data sets that can help inform the district’s overall communications practices. Superintendents often have access to information about student test scores, as well as broader community data and comparative data between campuses. Tech directors have direct access to device usage data, and comms directors have access to analytics for their communications tools, such as app usage and website traffic.

Together, all this information can paint a clearer picture of how each group of stakeholders is engaging with the district. Strong data can help a team better align to make the best choices for their shared goal.

Teamwork makes change easier to weather.

Given the discourse surrounding public education, both at the local and national levels, stakeholder trust in your schools has never been more crucial. And most people we talked to—whether researchers or district leaders—felt that challenges to school districts’ reputations will only intensify.

But the good news is this: Increased collaboration between the superintendent, CCO and CTO is your first step toward succeeding despite the odds. Districts thrive not because of their leaders’ individual talents, but because of those leaders’ dedication to working together—and always, always finding common ground in their purpose and work.